A New Photo Book Showcases the Absurd Extravagance of the World’s Wealthiest Citizens

Economic recession or not, there are few limits on the ways the mega-rich will flaunt their fortunes

Chinese businesswoman Xue Qiwen owns nine homes, which she prefers to stock with furniture from her favorite brand, Versace. A member of three golf clubs (each of which cost $100,000 to join), she insisted to photographer Lauren Greenfield, who took her portrait in 2005, when she was 43 years old, “I think for someone my age, everything should be more modest, not too flashy.”

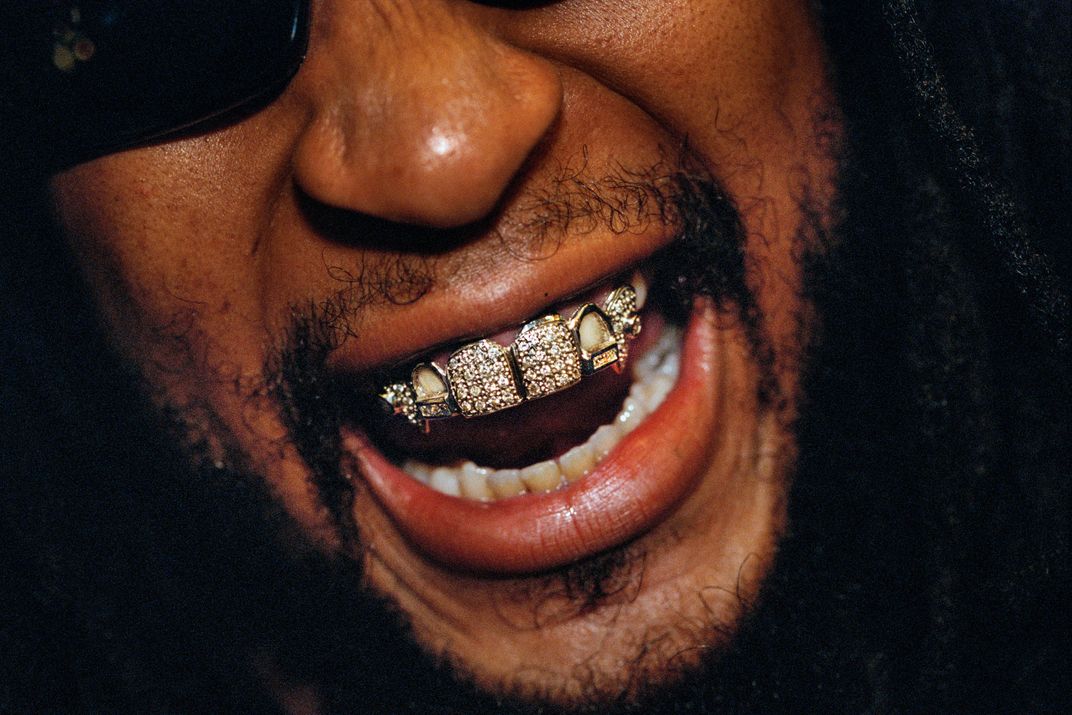

American rapper and hip-hop producer Lil Jon, only ten years younger, would likely disagree with that sentiment: He was happy to show Greenfield his $50,000 diamond and platinum grill at an awards show in 2004. And while Jackie Siegel, the beauty-queen wife of a time-share baron, might share Xue’s love of Versace (she and her friends are pictured in 2007 with the fashion house’s latest handbags), her quest to build America’s largest house was far from modest.

But “the desire for bling” cuts across gender, race, class and nationality, says Greenfield. Perhaps best-known for her 2012 documentary The Queen of Versailles, about Siegel and her family, she has spent the past 25 years photographing gilded heiresses, disgraced financiers and debt-laden middle-class folks trying to keep up with the Kardashians—creating a body of work collected in a sweeping new book, Generation Wealth. “It’s a shared culture of conspicuous consumption,” Greenfield says. “If you ask kids today what they want to be when they grow up, most of them say, ‘Rich and famous.’ ”

Greenfield grew up in Southern California, where her parents, academics dedicated to the anti-bourgeois values of the 1960s, raised their children largely in communes. But in 11th and 12th grade, she attended a tony private high school that exposed her to a different world. Greenfield’s classmates—many the offspring of entertainers and studio executives—drove fast cars, wore expensive clothes and boasted tickets to movie premieres. It was the 1980s, when money meant status, and status meant everything.

After college at Harvard, Greenfield returned west, embedding herself in her former high school to work on a photography project documenting the teenaged sons and daughters of Hollywood’s rich and famous. She partied with the Kardashian sisters when they were merely rich, popular preteens. She hung out by the pool with the sons and daughters of top talent agents. She attended the swanky bar mitzvah of a wizened13-year-old named Adam, who told her, “Money affects kids in many ways. It has ruined a lot of kids I know. It has ruined me.”

It wasn’t long before Greenfield realized the affluent, jaded teens of L.A. were merely at the epicenter of a cultural transformation that had begun to span the globe. So she expanded her focus, first to the upper-middle-class suburb of Edina, Minnesota, then to Las Vegas, Disney World and other hotbeds of American materialism. Finally, she turned her lens abroad, to places such as the shopping malls of the United Arab Emirates, the penthouses of Russian oligarchs and the pet spas of Shanghai.

“It’s a shared culture of conspicuous consumption,” she says. “The backdrop is, social mobility is becoming more and more elusive—and the fictitious representation of status has replaced it. For a lot of people in the book, they find out the hard way that this doesn’t end well.”

The photos in Greenfield’s book, with accompanying interviews, cover the period leading up to the 2008 global economic crash—and the recovery, during which the top 1 percent of the 1 percent—and those of us who merely aspire to their lifestyle—apparently failed to learn any lessons about money’s easy-come, easy-go nature. Seen together, it all amounts to a staggering indictment of materialism. But Greenfield also has sympathy for her subjects, many of whom are trapped by economic, social and psychological forces beyond their control. “In our culture, a lot of what drives us is this quest for more—money, fame, beauty,” she says. “This is an addictive quest. And you can know it’s bad, but you’re still addicted.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)