Amy Sherald was living in Baltimore and finishing up a graduate degree in fine art when, at age 30, she was diagnosed with a serious heart condition. Nine years later, in 2012, after a harrowing blackout episode, she received a heart transplant, which renewed her commitment to painting as well as her health. In 2016, she submitted one of her paintings, a portrait called Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance), featuring an elegant African-American woman holding an oversized teacup, to the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. No woman had won the contest in its 12 years. “The night of the award announcement, I thought, I’m not going to get one,” Sherald recalls. “Then I heard my name.”

She took the grand prize. “Sherald creates innovative, dynamic portraits that, through color and form, confront the psychological effects of stereotypical imagery on African-American subjects,” the citation said. The next year, first lady Michelle Obama selected Sherald to paint her official portrait, bringing unimagined public attention. When the painting was unveiled, in 2018, it drove record numbers of visitors to the National Portrait Gallery—so many the work was relocated to a larger room to accommodate the crowds.

This past fall, crowds flocked to view Sherald’s first New York solo exhibition, at the Hauser & Wirth gallery. The show, titled “the heart of the matter...,” consists of eight new portraits in rainbow hues, starring ordinary people Sherald had encountered by chance in Baltimore and New York and later photographed at her studio. Her subjects’ complexions, however, are painted in Sherald’s signature grisaille, or gray scale—“an absence of color that directly challenges perceptions of black identity,” the gallery says.

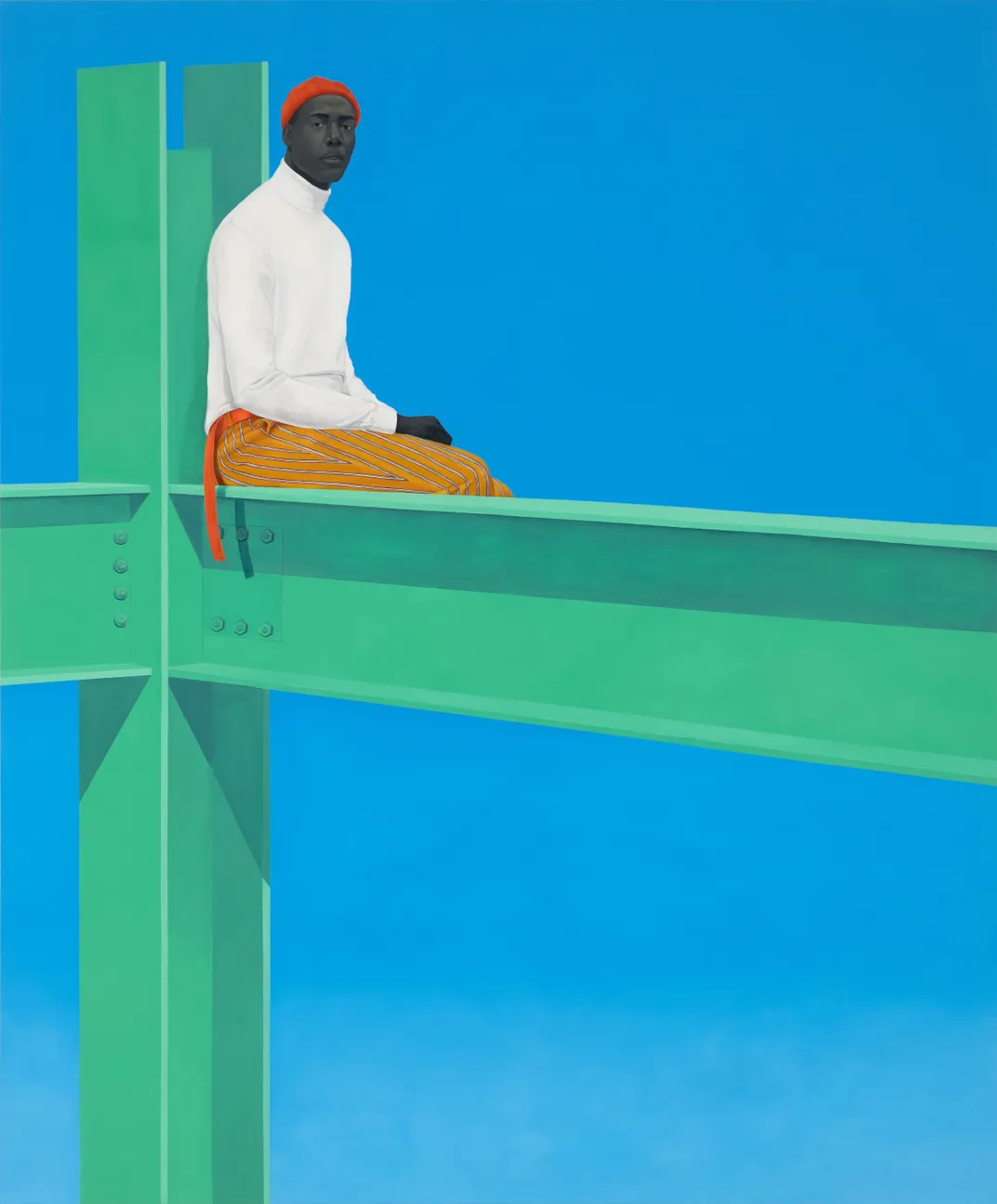

Nearly life-size, dressed casually or in work uniforms or in their Sunday best, her subjects invite viewers to linger and reflect. The gigantic 9-foot by 10-foot painting If you surrendered to the air, you could ride it (the title comes from Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon) shows a young man perched on a green construction beam, gazing toward and above the viewer—an ode to Charles C. Ebbets’ iconic photograph Lunch atop a Skyscraper that also subtly comments on the overlooked triumphs of black laborers in America. Another painting, Sometimes the king is a woman, shows a self-assured woman in a striking, black-and-white zigzag-patterned dress against a bright pink background. Her unassuming yellow earrings seem to whisper a charge to women everywhere—“The time is now,” perhaps.

On a brisk October afternoon, a line wraps around the block outside Hauser & Wirth in Manhattan. Inside, stylish patrons chat and snap selfies and stare at Sherald’s monumental paintings. In a back office, the artist sits with her dog, August Wilson, named for the playwright, to speak with Smithsonian.

What would people be surprised to know about you?

Many might be surprised to find out that if I wasn’t an artist, I might be a chef. I was really good at cooking, at a young age. As I work, I’ll have [the Netflix series] “Chef’s Table” playing in the background, because I find inspiration in their practices and what they do. We’re both working with these very basic, rudimentary tools. Broccoli is always going to be broccoli, there’s no new vegetable that’s going to pop up. Similarly, I work with brushes and paint. We take these tools and make something wonderful out of them.

How did winning the National Portrait Gallery’s competition affect your career?

The $50 submission fee is the best investment I ever made. I knew at that point in my career, after my heart transplant recovery, I needed something to put me out there. It definitely put me on an international stage and introduced many people to my craft. From there I obtained gallery status, which exposed my work to the art market. The paintings sold, and then suddenly there was a waiting list. I began a crazy work schedule knowing I needed to produce 12 paintings a year.

Where do you find your inspiration?

Reading—a lot of reading, which is a sacrifice I’ve had to make at this productive time in my career. I read to start a conversation with myself, to open me up. The bigger your vocabulary, visually and with words, the easier it is to communicate what you’re trying to put out there.

What is your favorite part of the artistic process?

I love doing the research, but painting the faces and eyes is the most fun part—I’m able to get to know my models in an intimate way.

You were raised in Columbus, Georgia. How did growing up in the South shape you?

It shaped my identity, my work ethic. It influenced how I saw myself, which wasn’t always positive. When I moved back to Columbus for four years to care for family, I thought about who I was in that environment, and how much I “turned on” around certain people. At times, I felt I had to prove to others that black people are better than they thought we were. Acknowledging the performative aspects of race and Southernness, I committed myself to exploring the interiority of black Americans. I wanted to create unseen narratives.

How did you determine what you wanted in your new show?

The show centers around self-love, and blackness—mostly informed by bell hooks’ 2001 book Salvation: Black People and Love. I borrow its first chapter for the title of the show, and hooks’ vocabulary brought me back to a personal love ethic: loving who I was, focusing on who I was on the inside and not thinking about the way that the world sees you.

And Kevin Quashie’s 2012 book, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture, informs my interest in interiority. The first chapter examines the image of the 1968 Olympics black power salute as a moment often read as resistance, although John Carlos and Tommie Smith are silent. There’s an undercurrent of emotion going on inside of them, which isn’t always considered.

So, when I began to think about interiority, I’m like, “That’s what it is.” My portraits are quiet, but they’re not passive. When you consider the African-American historical narrative and its ties to the gaze, a glance could result in punishment by lynching. I wanted my sitters to look out and meet your gaze, instead of being gazed upon. Essentially, that’s the beginning of selfhood, a consideration of self which is not reactionary to your environment.

Do you feel pressure to create art with a social justice bent?

A black person on a canvas is automatically read as radical. In hindsight, I look back and I’m like, that’s why my figures are gray. I didn’t want the conversation to be marginalized, and I had a fear of that, early on. My figures needed to be pushed into the world in a universal way, where they could become a part of the mainstream art historical narrative. I knew I didn’t want it to be about identity alone.

What’s next for you?

Right now I’m focused on being in the studio. The more museum spaces that I can fill up, the more change these paintings can project. They can be employed in many different ways, but hanging them on walls in accessible public spaces is essential. If you know African-American history, then you recognize the power of their presence.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

To learn more about Sherald, listen to this episode of Sidedoor, a Smithsonian podcast, from the show's second season:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/9a/149a1332-6203-4124-ab3f-07f118f2d2a6/amy_sherald_mobile.jpg)

:focal(1323x304:1324x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/a6/aca6fc12-bb70-4ad9-bd36-808ad28cb46e/visual_arts.png)