New York Fashion Week, Past and Present

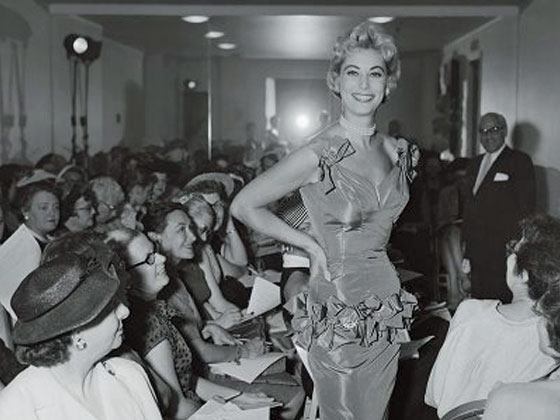

Since the mid-1940s, models of perfection in designer clothes have graced Manhattan runways every autumn

![]()

Today kicked off New York Fashion Week, the debut of the Spring 2013 designer collections, and for the next seven days, if you don’t catch them on the runway, you may run into six-foot-tall models on the subway, post-show, in cut-offs and T-shirts, faces still made up.

Twice a year, like clockwork, I expect a few NYFW constants: lithe models teetering (or taking a spill) on the catwalk; Anna Wintour, expressionless, seated in the front row; popping flashbulbs; PR girls with headsets; celebrities rubbing elbows. It’s been like that as long as I can remember, but in the scheme of things, that isn’t all that long. How did this annual see-or-be-seen spectacle come to be?

When U.S. journalists couldn’t travel to Paris Fashion Week after Germany occupied France during World War II, a fashion week in New York was the creative response. Fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert dreamed up an event where editors could direct their attention to the sartorial splendor of American fashion designers who had gotten very little love from national or international press. Until that time, U.S. designers and editors had relied heavily on Parisian couture for inspiration.

But in 1943, that all changed with the first Press Week, the term Lambert coined before it was officially called Fashion Week. On their home turf (or, well, runway), American designers presented their American-influenced clothing constructed from American-made materials to editors (and only editors—buyers weren’t allowed to attend the fashion shows and instead made showroom visits).

Rather than the later practice of editors, buyers, bloggers and groupies frantically crisscrossing the city to get from one show to the next, in those days, the shows came to the editors. They planted themselves at the Pierre and Plaza hotels, taking copious notes from show to show.

Lambert’s vision worked. Editors began name-checking designers who showed at Press Week—Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, Mollie Parnis, Pauline Trigere and others—in magazines like Vogue and Bazaar, an about-face from the U.S.’s Francophilic inclinations.

Fashion Week continued uninterrupted through the decades, and by the ’70s and ’80s, shows were being staged in creative spaces around New York like lofts, galleries, nightclubs and restaurants. But, after an incident in 1990 during a Michael Kors show in a gritty loft, the tide shifted again. When bits of the plaster ceiling collapsed onto the well-coiffed heads of fashion editors, Fern Mallis, then executive director of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (the organizing body of Fashion Week), decided it was time for an upgrade. She’s quoted as saying, “The general sentiment was, ‘We love fashion but we don’t want to die for it.’ ”

So, after a couple of experiments and a lot of cajoling, Mallis not only persuaded the privately owned Bryant Park to erect two white tents, but also persuaded designers to show their collections under those tents. In the spring of 1994, the first shows took place at the park, drawing greater international attention to U.S. designers. The shows continued unabated until September 11, 2001, when Fashion Week, scheduled to begin on the day of the terrorist attacks, was canceled. In 2009, many designers downsized or opted out from Fashion Week because of the poor economy. In 2010, after some hiccups at Bryant Park, Fashion Week moved to Lincoln Center where it remains today.

Even though glitz and glamour take center stage during New York Fashion Week, it’s worth noting that showings still take place in old loft and tight showrooms, on unexpected catwalks and with runway-free presentations. Harkening back to decades past, these events are put on by up-and-comers and independent designers who are willing to think outside the tent.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)