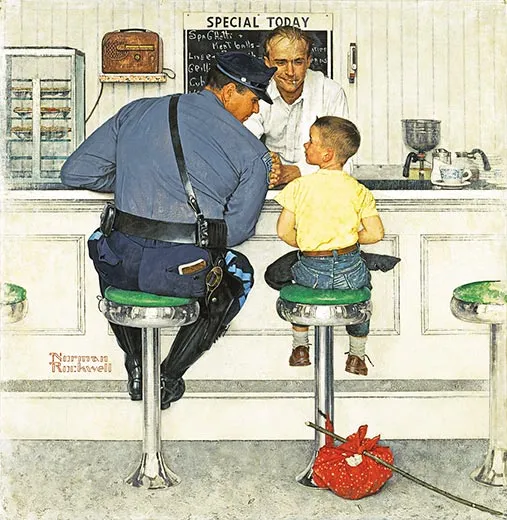

Norman Rockwell’s Neighborhood

A new book offers a revealing look at how the artist created his homey illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Norman-Rockwell-The-Runaway-631.jpg)

If you lived in Arlington, Vermont, in the 1940s, or in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, in the '50s, chances are you or someone you knew appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post. Norman Rockwell's cover illustrations, which adroitly captured the nation's homiest images of itself, were based on the neighbors and surroundings the artist saw every day. He enlisted as models not only his friends and family members but also strangers he met at the bank or at a high-school basketball game.

The camera played a vital, if little-known, role in Rockwell's high fidelity, as Ron Schick's new book, Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, makes clear. Schick, who was given access to the entire archive at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge (where a companion exhibit is on view through May 31, 2010), learned that Rockwell first made extensive use of the camera in 1935 while scouting Hannibal, Missouri, for an illustrated volume of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. At first, the artist thought using a camera instead of a pencil was "cheating" and said he was "thoroughly ashamed" of tracing details from projected images. But photography, Schick writes, "transformed Rockwell's work; it instantly unlocked his aesthetic, enabling him to execute whatever he envisioned."

Rockwell would choose and decorate sets, select props, outfit and coach the actors and decide where to place the tripod, though he usually left the pressing of the shutter to an assistant. The resulting photographs, Schick says, "are like Rockwell's paintings come to life. You can explore the decisions he made. It's like watching a slow-motion film of his process." The artist himself appears in some of them, mugging and gesticulating as he acted out the roles ("He was a ham," Schick says), and he was not above banging his fist to elicit a startled expression from his subjects.

In 1958, Rockwell asked Massachusetts State Trooper Richard J. Clemens, 30, who lived a few doors from the artist in Stockbridge ("Mr. Rockwell's dog would wander into my yard"), to pose for a painting that would become a cover illustration called The Runaway.

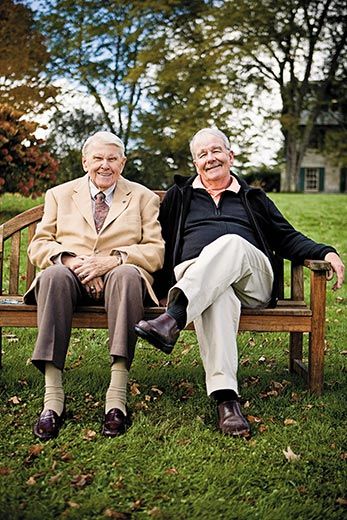

"I was told to be in my uniform at the Howard Johnson's [restaurant] in Pittsfield," recalls Clemens, now 81 and retired in Clifton Park, New York. Inside, he was introduced to 8-year-old Eddie Locke, whose father and brother Clemens already knew. Rockwell had recruited the boy from the local elementary school to play a plucky young vagabond.

To underscore the lad's meager possessions, Rockwell placed a handkerchief on a stick beneath the stool. For about an hour, Clemens and Locke sat as still as they could while the maestro adjusted their postures ("Keep one arm extended") and expressions ("Look this way and that"). "I was a little kid, but he made it easy on me," says Locke, 59, a landscaper and maintenance worker in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Clarence Barrett, a friend of Rockwell's who worked at a local garage, manned the counter.

But when The Runaway appeared on the cover of the September 20, 1958, Saturday Evening Post, Barrett had been replaced with Rockwell's assistant Don Johnson, who had been photographed separately in the artist's Stockbridge studio. And all references to Howard Johnson's had vanished. When Clemens asked why the restaurant's celebrated 28 flavors of ice cream (listed on the mirror) had been replaced with a blackboard list of daily specials, Rockwell said he "wanted a more rural look, to suggest the kid had gotten a little further out of town. That's the kind of detail he went in for."

Clemens says his police supervisors were "very pleased a Massachusetts trooper had been chosen for a magazine cover." In fact posters of the tableau were soon hanging in law enforcement agencies throughout the country. (To show his appreciation of the force, Rockwell painted a portrait of Clemens in his winter trooper's cap and gave it to the state police, who reproduced it as a Christmas card.)

Locke also recalls posing as a boy awaiting the doctor's needle in Before the Shot, a Rockwell illustration that appeared on the Post's cover of March 15, 1958. The assignment required that he drop his trousers just enough to expose the upper part of his buttocks. "As you might imagine, I got teased about that," Locke says. "I played baseball as a kid, and I pitched. I always claimed that I learned how to throw inside early on."

Richard B. Woodward, a New York City-based arts critic, wrote about Ansel Adams in November's Smithsonian.