Norman Rockwell’s Storytelling Lessons

George Lucas and Stephen Spielberg found inspiration for their films in the work of one of America’s most cherished illustrators

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Norman-Rockwell-Movie-Starlet-And-Reporters-631.jpg)

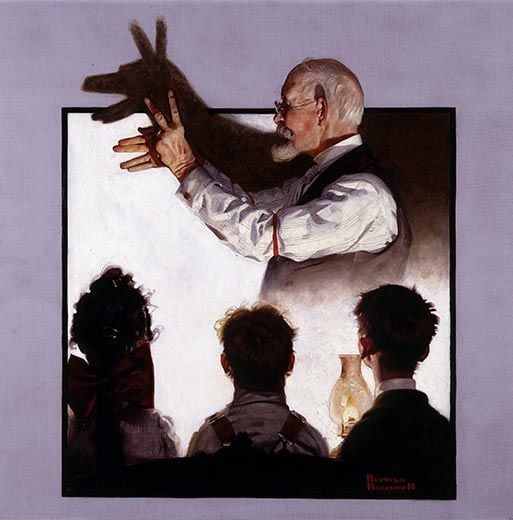

What draws two of the world’s most successful filmmakers to the same famous American illustrator? The answer may lie in a 1920 canvas called Shadow Artist, the picture portrays a gray-haired, goateed man in a vest and shirt sleeves standing in front of a kerosene lamp creating with his hands a wolf silhouette of a wolf—we can easily imagine the bloodcurdling sound effects—for a rapt audience of three young people whose hair seems almost to be standing on end.

Reduced to its essence, this is what George Lucas and Steven Spielberg do: create illusions on a vertical reflecting surface to attract, amuse and amaze their audiences. It is also what figurative painters and illustrators do, which makes Norman Rockwell, the prolific illustrator of hundreds of Saturday Evening Post and other magazine covers, their creative cousin and fellow storyteller.

Shadow Artist is one of 57 works on view in “Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through January 2, 2011, a study in the convergence of three artistic visions.

Exhibition curator Virginia Mecklenburg said the idea for the show arose from Barbara Guggenheim, the Los Angeles-based art consultant and member of the museum’s collectors group who knew the Spielberg Lucas collections well. “As soon as I heard about the idea for a Rockwell exhibition,” Mecklenburg told me, “I said ‘Please, please, please!’ I’ve been fascinated by his paintings and drawings since I was a child. Working on the show gave me a chance to explore Rockwell’s associations with the movies and the pop culture that was going on at the time Rockwell did the pictures. It’s almost like archaeology.”

In an essay for the exhibition’s catalog, Mecklenburg tells of the effects of Rockwell’s covers for the Saturday Evening Post on both Lucas and Spielberg. Lucas, who spent his childhood and high-school years in the Central Valley California town of Modesto, says that he grew up “in the Norman Rockwell world of burning leaves on Saturday morning. All the things that are in Rockwell paintings, I grew up doing.”

Like the two moviemakers whose collections form the museum’s show, I remember Rockwell’s Post covers well. Three magazines formed my family’s weekly connections to the world beyond our small New Jersey town: Life, Harper’s Bazaar and the Post. Life was the pre-television source of visual news, Bazaar kept my fashionable mother chic and the Saturday Evening Post delighted me with visions of Norman Rockwell’s world that looked comfortingly familiar to me. It happens (to close a circle) that not so long ago I worked at Skywalker Ranch, the remarkable compound that George Lucas built in the rolling hills of Northern California to be the headquarters for his film company. In the stately main house, where I often had lunch, I was able to renew my boyhood pleasure in Rockwell’s world by looking at some of the pictures on the wood-lined walls. (The house, built in the mid-1980s in the style of a turn-of-the-century Victorian ranch house, is another of Lucas’ illusions.)

Serious art critics often dismiss Rockwell as a cautious and calculating master of the middle way, a kind of mild moderator of lives too sweet and too narrow. It’s hard to argue that Rockwell was a challenging artist, but there are people—George Lucas is one and I’m another— who actually did grow up in the world he depicts. Rather than being a cockeyed optimist, Rockwell could be—occasionally—withering in his characterizations, as in a 1929 Post cover that shows three closely huddled gossips, clearly at work ruining small-town reputations.

In a catalog preface, Elizabeth Broun, the Margaret and Terry Stent Director at the museum, writes that “Rockwell’s pictures populate our minds…. They distill life into myth by simplifying, connecting dots, creating story lines, and allowing us to find useful meaning in events that are often random, disconnected, or without moral perspective.” This same description might easily be applied to many Steven Spielberg movies—especially the aspects of simplification and moral perspective. Even with its jarring battle scenes, Saving Private Ryan is far closer in its influence to Rockwell than to the ironic, existential World War II cartoons of Bill Mauldin.

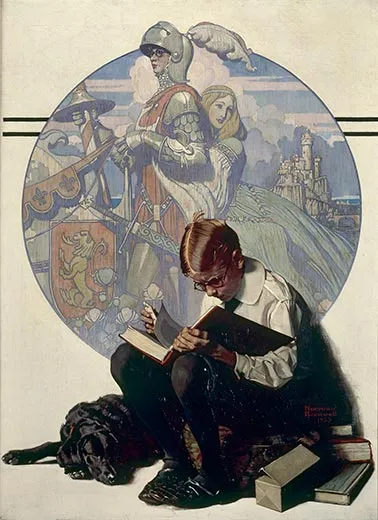

That same influence can be seen in Lucas’ early films, before Darth Vader, Yoda and digital special effects made their lasting mark. In particular, American Graffiti is Rockwell’s vision brought to life in seamless concert with the director’s vision, and Raiders of the Lost Ark, while also paying homage to classic boys’ adventure tales, presents Indiana Jones as the kind of Hollywood hero who might have sprung straight out of a Saturday Evening Post cover. Referring to one of the pictures in his collection, Boy Reading Adventure Story, Lucas talks in the catalog about “the magic that happens when you read a story, and the story comes alive for you.”

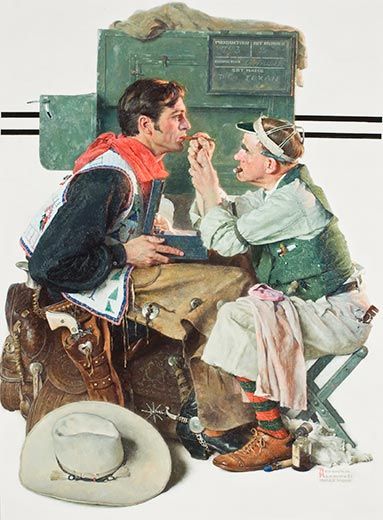

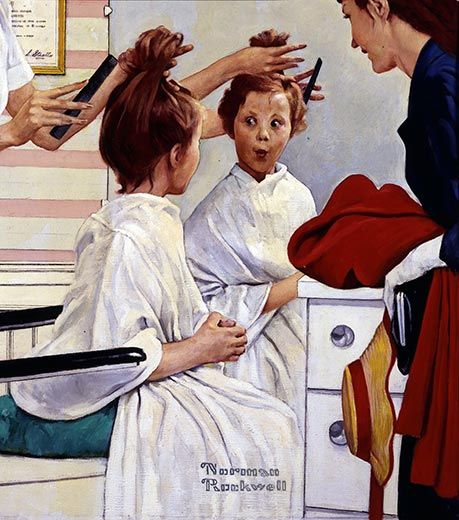

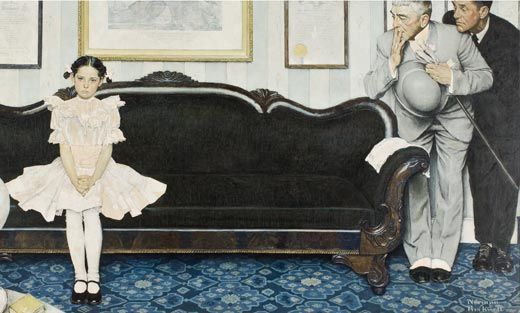

It is Rockwell’s interest in Hollywood that makes the most direct connection with Spielberg and Lucas as collectors. The artist made the first of many visits to Los Angeles in 1930, at the age of 36; he would eventually become more famous as an illustrator than such renowned predecessors as N. C. Wyeth and J. C. Leyendecker (creator of the “Arrow Collar Man”), but he was already well known enough to have access to film studios. Part of the Spielberg collection is a funny, myth-busting picture of a young Gary Cooper, in full cowboy regalia, having makeup applied before filming a scene for The Texan. Another wry commentary on the Hollywood scene, used as the cover image on the Smithsonian exhibition catalogue, is a picture of six rather seamy members of the press desperately trying to interview a blond, vacant-looking starlet. Though she somewhat resembles Jean Harlow, the actual model was a young, aspiring actress named Mardee Hoff. As proof of Rockwell’s influence, within two weeks of the picture appearing as a Post cover Hoff was under contract with Twentieth Century Fox.

Rockwell used the techniques of a film director to create his scenes. He hired models—often several, depending on the picture—and carefully placed them, for charcoal sketches and later for photographs. Most successful illustrators made their reputations and livings on precise verisimilitude, but Rockwell’s skills were so formidable that he can be seen as a precursor of the Photo Realists of later decades. His pictures draw us into the scene, letting us forget the involvement of the artist and his artifices, in the same way a good director erases our awareness of crews and equipment and the other side of the camera. Rockwell has the power to win us over with his illusions. As Steven Spielberg put it, “I look back at these paintings as America the way it could have been, the way someday it may be again.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)