One Man Band

The next Bob Dylan? Maybe. Sufjan Stevens’ honest sound and stark lyrics speak volumes to a new generation. And he plays all the instruments

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/yi_stevens388.jpg)

On his debut album, A Sun Came, which appeared in 2000, Sufjan Stevens sang, played all the instruments—piano, electric guitar, oboe, banjo, sitar and xylophone—wrote the melodies and lyrics and even recorded it himself, on a four-track cassette tape recorder. Since then, he has staked out a place in the world of indie rock as a composer and songwriter of extraordinary depth, with a sound that might be described as very new and yet strangely Old World. Stevens, London's Observer noted, is "one of the most compelling new voices in American music." The New York Times called him a "cult figure who happens to be a major artist."

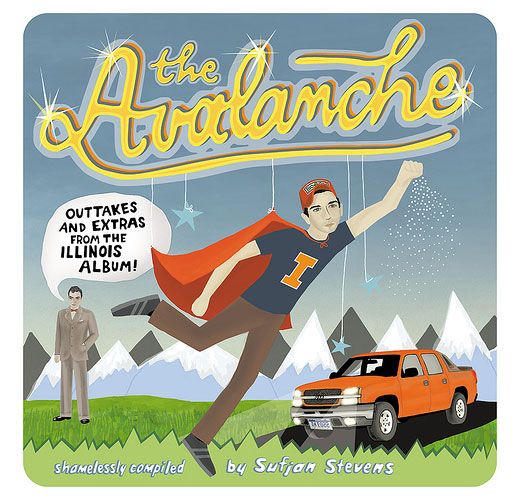

His second release, Enjoy Your Rabbit, is a collection of electronic instrumentals, each named after a Chinese zodiac symbol. He followed that in 2003 with Michigan, an homage to his home state, and announced his intention to record an album for every state. Although he has since tackled Illinois with Come On, Feel the Illinoise—one of the most critically acclaimed albums of 2005—he admits that "at this rate, I probably won't get many done in my lifetime." The albums have all been released on the Asthmatic Kitty label, which he founded with his stepfather.

His "old" sound and intense, starkly personal lyrics make more sense when you know his history. Stevens' parents, who both belonged to the Eastern religious sect Subud, separated within months of his birth in 1975. Sufjan and his siblings (one brother and two sisters) went to live with his father, who soon remarried. With his stepmother's daughter from a previous marriage and a baby brother born into the new family, Stevens felt he was living in what he calls a "dysfunctional Brady Bunch."

"There were no lessons, there wasn't the consistency that the Brady Bunch had," adds Stevens, 32. "I did a lot of just watching and observing them." The family lived at the edge of a run-down Detroit neighborhood. "I remember Detroit feeling really unsafe, feeling scared a lot. Our house was broken into, our car was stolen, we had to get a watchdog, we would get beat up in the street, I had my bike stolen. There was just a lot of real anarchy on the streets and sidewalks." He says moving five hours north into a great-grandmother's house in the tiny defunct lumber town of Alanson came as a relief. The only problem was that as a summer home, it had no insulation or heat apart from a small wood stove. In winter, the family would seal off the top half of the house and sleep downstairs. "For a while there was no washer and dryer, so we would plunge the clothes in the bathtub. The water heater was really small and old, so we ended up boiling hot water. It felt like Uncle Tom's Cabin or something, really backwoods,

and almost kind of like a historical, very simple way of life."

At the time, the only music in Stevens' life was Casey Kasem's Top 40, which the preteen listened to religiously every week. "We had an old, out-of-tune piano in the house. It was really ornate with the ivory keys peeling off. My sister took lessons, and she would practice every once in a while and she would hate it. I would listen to her, and when she was done I would go to the piano and try to play what she had played based on memory." At public school he took up the oboe. "I wanted to play trumpet, but there were so many kids signed up for trumpet that the teacher decided I would be a good oboist. I practiced a lot just because there was nothing else to do." Stevens enrolled at Interlochen, a private music and arts school in northern Michigan, where he began "envying the kind of brilliance and romance that the [piano players] could create on this beautiful, dynamic instrument." At the same time, Stevens began a quest for something in which to ground himself—and found it in Christianity. "I didn't have a born-again experience, although I would describe myself as born again, and I don't know how to reconcile that. If anything, it was this very slow and casual evolution that urged me toward Christianity."

At Hope College in Michigan, Stevens formed a band, Marzuki, with three pals. "My friend in the band loaned me this nylon-string guitar the summer after my freshman year. Then I bought a cassette tape four-track recorder. I would just strum the hell out of that guitar, and I would learn different chord charts and fingerings and play for two or three hours, just recklessly strumming A minor and E major and D major over and over again trying to learn this guitar. And the guitar was so inspiring because it was portable and very familiar and very small and it was something you embodied because you held it." In an audio-recording class taught by John Erskine, a sound engineer who had worked with such bands as Sonic Youth, Stevens transferred a lot of his four-track tapes into a digital format. The result was his first album, "basically a really convoluted overextended collection of songs," he says. "It's almost like a demo of sorts."

After graduation, Stevens went to New York City, where he worked as a designer for a publisher and took night classes in writing at the New School for Social Research. "I took workshops and went to readings and basically tried to network and get to know as many agents and publishers as I could because I was really fixated on getting published. I just felt like the music was a distraction, that it had gotten me nowhere."

After two years, Stevens found himself broke and unemployed. "That's when I sort of started writing songs for Michigan," he says. "It was a slow, progressive thing," he says, referring to how the album caught on. "Six months later, it landed on a lot of year-end lists as one of the top albums of the year."

At the moment, Stevens, who lives in Brooklyn, is composing, among other things, a symphonic piece with the Brooklyn Academy of Music celebrating the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Yet, he says, "this is the first time in a long time that the future is really unknown. Because I had lived my life with so many goals and so many aspirations and so many plans, and I've come to the realization that I no longer need to create that kind of structure. That I don't need to be so goal-driven. So right now I'm just taking the year to write and to work on a lot of other projects, and to maybe go back to fiction writing."

Among America's most influential disc jockeys, Nic Harcourt is music director of KCRW, Santa Monica, and host of its "Morning Becomes Eclectic" and the syndicated "Sounds Eclectic."