Only a Handful of People Can Enter the Chauvet Cave Each Year. Our Reporter Was One of Them.

A rare trip inside the home of the world’s most breathtaking cave painting leaves lasting memories

The entry into the depths of the Chauvet Cave, the world’s greatest repository of Palaeolithic art, begins with a dramatic ascent. A steep switchback trail through a forest brings one to the foot of a limestone cliff. From here a wood-plank walkway leads to a steel door. Behind it, sealed from outsiders by four secure locks- including a biometric lock accessible by only four conservators - lies a time capsule that remained hidden from the world for 35,000 years.

Ever since three amateur spelunkers, led by Jean-Marie Chauvet, crawled into the cave on December 18, 1994, and stumbled upon its remarkable trove of drawings and engravings, the government has sharply restricted access in order to preserve its fragile ecosystem. I had been as far as this entrance four months earlier, while researching a cover story about Chauvet for Smithsonian. Back then, I had to settle for entering the Caverne Pont D’Arc, a $60 million facsimile then under construction in a nearby concrete shed. But in April, in advance of the facsimile’s opening to the public, France’s Ministry of Culture invited me and three other journalists on a rare guided tour of the real Chauvet.

Marie Bardisa, Chauvet’s chief custodian, opened the steel door and we entered a cramped antechamber. Each of us slipped into the obligatory protective gear, including rubber shoes, a blue jumpsuit, a helmet mounted with a miner’s lamp, and rope harness fitted with two caribiners. Feelings of claustrophobia began to take hold of me as I crawled through a narrow rock passageway that ascended, curved, then descended, and finally stopped just before an abyss: a 50-foot drop to the grotto floor. A permanent ladder is now in place here. Bardisa’s assistant clipped our caribiners to a fixed line and we descended, one by one, into the darkness.

All these precautions are in place to protect the cave itself and avoid repeating what happened to the famous Lescaux caves, where bacteria and decay have ruined the cave art. As I wrote in my Smithsonian feature:

The cave’s undoing came after the French Ministry of Culture opened it to the public in 1948: Visitors by the thousands rushed in, destroying the fragile atmospheric equilibrium. A green slime of bacteria, fungi and algae formed on the walls; white-crystal deposits coated the frescoes. In 1963 alarmed officials sealed the cave and limited entry to scientists and other experts. But an irreversible cycle of decay had begun. Spreading fungus lesions—which cannot be removed without causing further damage—now cover many of the paintings. Moisture has washed away pigments and turned the white calcite walls a dull gray. In 2010, when then French President Nicolas Sarkozy and his wife, Carla Bruni-Sarkozy, toured the site on the 70th anniversary of its discovery, Laurence Léauté-Beasley, president of a committee that campaigns for the cave’s preservation, called the visit a “funeral service for Lascaux.”

At Chauvet, however, Just 200 scientific researchers and conservators are permitted inside each year. Bardisa says that as long as they stringently restrict access and closely monitor the cave, it can continue in its present state for the foreseeable future.

Because I had already toured the facsimile in December, I thought I would have some idea of what to expect. But nothing could have prepared me for Chauvet’s vastness and variety. (The Caverne Pont d’Arc has been shrunk to one third of the real cave’s 8,500 square meters.) The lamp on my miner’s helmet, along with a seepage of natural light, illuminated a cathedral-like gallery that soared at least six stories high. As we trod along a stainless-steel walkway that retraced the original explorers’ path – warned by Bardisa not to touch anything and remain on the walkway at all times - I stared at an extraordinary panoply of colors, shapes and textures.

White, purple, blue, and pink calcite deposits –formed over eons by water seeping through the limestone - suspended from the sloping ceiling like dripping candle wax. Multi-armed stalagmites rose from the floor like saguro cacti. Others poked up like sprouting phalluses. There were bulbous formations as elaborate as frosted, multi-tiered wedding cakes, clusters of dagger-like stalactites that seemed ready to drop off and impale at us any moment.

Some limestone walls were dull and matted, while others shone and glinted with what seemed like mica. The floors alternated between calcified stone and soft sand, embedded with the paw prints of prehistoric bears, ibexes and other animals. The prints in the soft ground, frozen in place for 35,000 years, could be destroyed by a simple touch, Bardisa warned. And everywhere lay remnants of the beasts that had shared this cave with human beings: bear and ibex skulls, little white islands of bear bones, the droppings of a wolf.

The natural concretions were splendid, but it was, of course, the drawings that we had come to see. The presence of Palaeolithic man revealed itself slowly, as if these ancient cave artists had an intuitive sense of drama and pacing. In a corner of the first gallery, Bardisa pointed out the tableau that had mesmerized the French cave-art expert Jean Clottes when he entered here in late December 1994 to authenticate the discovery: a grid of red dots covering a wall, created, as Clottes would determine, by an artist dabbing his palms in ocher then pressing them against the limestone. Clottes developed a theory that these early cave artists were prehistoric shamans, who attempted to communicate with the animal spirits by drawing them out of the rock with their touch.

We continued along the metal walkway, slightly elevated off the soft ground, following a sloping course through the second room, containing another large panel covered with palm prints and, here and there, small, crude drawings of woolly mammoths, easily missed. Indeed, Eliette Brunel, the first to enter the cave, had noticed none of these paintings on her first walk through. It was in a passageway between the second and third galleries that Brunel had caught sight of a small, smudged pair of ocher lines drawn on the wall to her right at eye level.

“They have been here,” she cried out to her companions. Over the next few hours, she, Chauvet and Hillaire moved from gallery to gallery, as we were doing now, staring in amazement as the representations of ice age beasts became more numerous and more sophisticated.

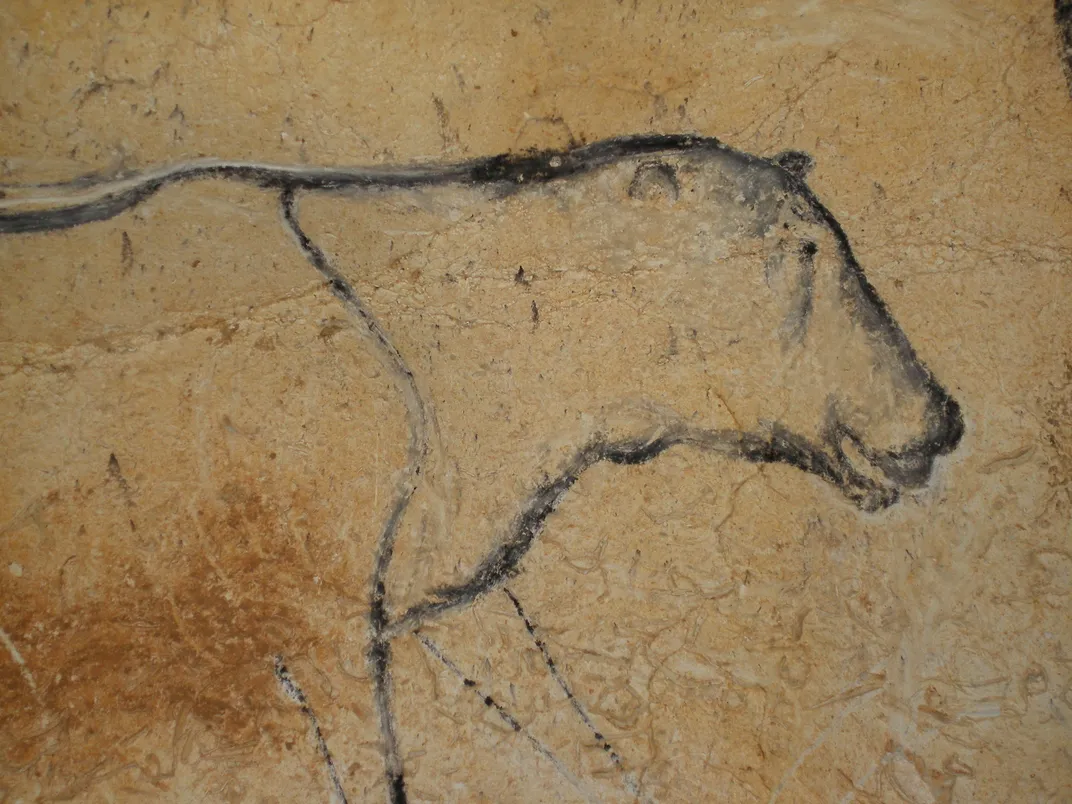

Kneeling down in the third chamber, I set eyes on a long panel of rhinoceroses at waist level. Then came a panel of white engravings – the first artwork we had seen that was not created using ocher paint. Made by tracing the fingers over the soft limestone, or by using crude tools, the etchings included a profile of a horse that seemed almost Picasso-esque in its swirling abstraction. “You can see it springing. It’s magnificent,” Bardisa told us. I had to agree.

A final passageway, hemmed in by sloping walls, brought us to the End Chamber.

The prehistoric artists, creeping into the cave’s hidden recesses with their torches, had obviously deemed this gallery the heart of the spirit world. Many visitors, including the filmmaker Werner Herzog, the director of the Chauvet documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams, had marveled at the paintings contained in this last gallery – perhaps the fullest realization of Paleolithic man’s imagination. Here, the artists had changed their palette from ocher to charcoal, and the simply outlined drawings had evolved into richly shaded, torqued, three-dimensional creatures, marvels of action and perspective. Across one 12-foot slab of limestone, lions captured in individualized profile stalked their prey –a menagerie of bisons, rhinos, antelopes, mammoths, all drawn with immeasurable skill and confidence.

After admiring this crowded canvas, we retraced our steps through the cave. I hadn’t been able to take photographs and had found it too awkward to scribble my thoughts in a notebook, but I retained a vivid memory of every moment of the two hours that I had been permitted to explore Chauvet. I climbed back up the ladder and removed my protective gear, punched the exit button and stepped into the bright sunlight.

As I made my way down the pathway to a parking lot far below, my mind still reeled with the images that had sprung dreamlike out of the darkness- as vibrant and beautiful as they had been when our distant ancestors first painted them on Chauvet’s limestone walls.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)