Out of Africa

This month a special collection representing most of Africa’s major artistic traditions goes spectacularly on view

Two exquisite pieces of art—an ivory female figure and a copper-alloy mask, both from the African Kingdom of Benin in Nigeria—provided the spark for a lifelong love and pursuit of African art for real estate developer Paul Tishman and his wife, Ruth. For 25 years, they gathered works from the major artistic traditions on the African continent. The result is a magnificent private collection.

Thanks to a very generous gift from the Walt Disney World Company, which has owned it since 1984, all 525 pieces of the Walt Disney-Tishman African Art Collection now belong to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art (NMAfA). Starting this month and running through next year, 88 of them will be displayed in an exhibition called "African Vision." Every piece in the exhibition will also be included in a full-color catalog (available for purchase through the Web site listed at the end of this column).

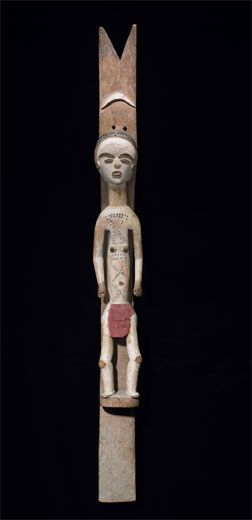

The exhibition and the Walt Disney-Tishman African Art Collection are an enormous source of pride for the Smithsonian. Not only does the collection reflect a broad swath of African art, but many of the items in it are historically important. Among them are a carved ivory hunting horn from Sierra Leone dating to the late 15th century and a wooden figurative sculpture from Cameroon that was one of the first African artworks ever displayed at the Louvre. Included also are traditional African masks and objects, large and small, that have never been exhibited before. Spanning five centuries and representing some 75 peoples and 20 countries, the Disney-Tishman collection is now unmatched as a private collection in its diversity and breadth. According to both scholars and art historians, its individual objects have shaped modern art, and the collection as a whole has defined African art.

The Disney-Tishman collection's importance can be traced directly to the Tishmans. They believed deeply that even a private collection should be accessible to the public. In fact, it was the desire to share the art with as many people as possible that led them to sell their collection to the Walt Disney Company. (Paul Tishman died at age 96, in 1996; Ruth Tishman died at age 94, in 1999.) The original plan was for a permanent exhibition space at Walt Disney World. While that dream never came to light (animators did, however, study pieces while making The Lion King), Disney continually lent collection pieces for exhibition and publications. Then, when the company decided to pass the collection on and was approached by many museums, it chose the Smithsonian.

Making such art available to visitors from all over the world is an important part of the Institution's mission as well as the particular focus of the National Museum of African Art, America's only museum dedicated to the collecting, conservation, study and exhibition of traditional and contemporary African art.

Through "African Vision," museum programs, and the lending of pieces to Smithsonian Affiliates and other art institutions throughout the world, NMAfA will honor both the Tishman tradition and the legacy of James Smithson, the Institution's founding benefactor. That is why there is not a more fitting home for what the museum's director, Sharon Patton, has called the Disney-Tishman collection's "coming out party."

When Paul Tishman was asked about his passion—about why he and Ruth collected art, specifically African art—he often responded with a question of his own: "Why do we fall in love?" After studying the artworks on this page and the article Cache Value, we think you'll agree that his was the perfect question—and answer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lawrence-small-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lawrence-small-240.jpg)