Owney the Mail Dog

For nine years, Owney rode the rails and the wagons on top of mailbags as the mascot of the mailmen

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Owney-Paul-Rhymer-631.jpg)

He was one of the most recognized celebrities of the late 19th century. Born of humble beginnings, he made frequent public appearances alongside those of noble lineage. He traveled the nation, receiving medals and gifts wherever he went. Later he toured the world as a goodwill ambassador.

Today, a new exhibit at the National Postal Museum is dedicated to the life and achievements of Owney, the terrier-mix dog who served nine years as the unofficial mascot of the U.S. Railway Mail Service.

“One of the reasons he was so popular is that he was this scruffy mutt who achieved way beyond his stature,” says museum curator Nancy Pope.

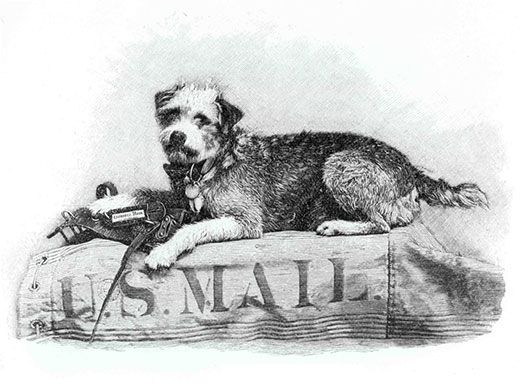

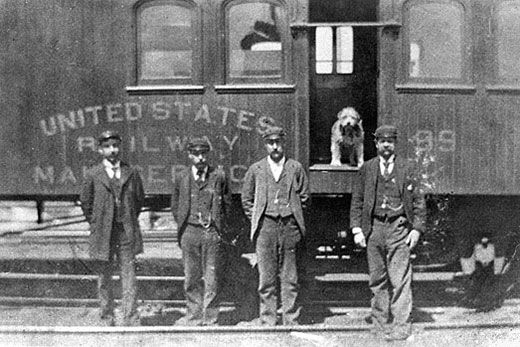

Owney began his public service career in 1888, after his owner—a postal clerk in Albany, New York—abandoned him. The other clerks took him into their care and Owney bided his time, sleeping on mailbags. When the mailbags moved—first to the mail wagon and then to the railway station—Owney went with them. At first, the four-legged postal carrier rode local trains, but he eventually traveled throughout the United States.

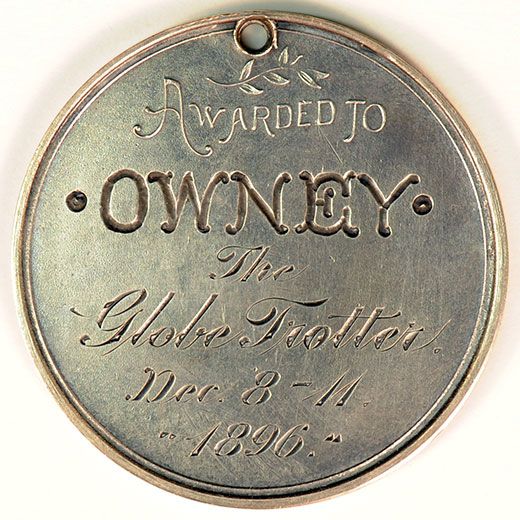

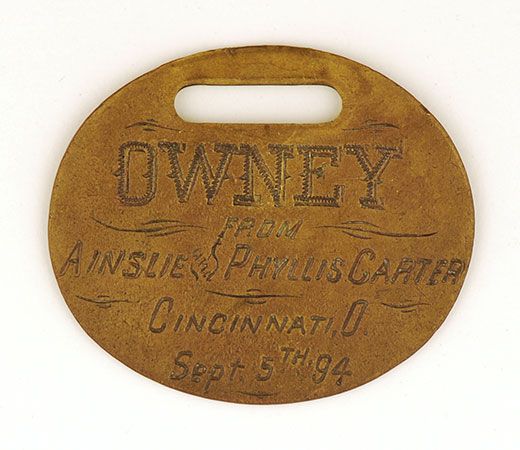

As newspapers began chronicling his travels in the early 1890s, Owney’s fame grew. The clerks outfitted their mascot with a collar, which accumulated medals and tags with each city he visited. When there were too many tags to fit on the collar, Postmaster General John Wanamaker gave Owney a harness for them. He became a popular special guest at dog shows and, in 1895, he embarked on a 129-day “Around the World” publicity tour aboard the Northern Pacific mail steamer Victoria.

The biographies of famous public figures are often embellished, and Owney was no exception. So, in 2009, when the National Postal Museum decided to create a new Owney exhibit, Pope, with the help of then museum intern Rachel Barclay, researched an exhaustive history of Owney’s life and travels—combing through newspaper articles and railroad maps, as well as the tags and medals Owney received when riding the rails. Sure enough, they debunked some myths, including that Owney was a stray who had wandered cold and hungry into the Albany post office one night.

While the mascot’s actual age was never known, by 1897 he had become old, ill and crotchety. After he bit a mail clerk, a deputy U.S. marshal was sent to investigate; Owney tried to attack him and was fatally shot. Mail clerks raised money to have his body preserved by taxidermy. His mortal remains were kept on display at the U.S. Post Office Department headquarters in Washington, D.C. until he was donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1912. Owney was moved to the Postal Museum when it opened in 1993.

For the new exhibit, Pope and museum conservator Linda Edquist wanted Owney to look his best, so they sent him to taxidermist Paul Rhymer. “It really is a miracle that he came in as good shape as he did,” Rhymer says. It took him a month to complete the canine’s first major restoration in his years on display. (During his absence, the museum made do with a stand-in, dubbed “Phony Owney.”)

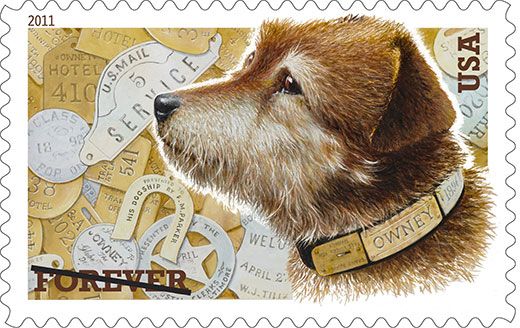

This past July, the U.S. Postal Service honored its fallen colleague with a stamp bearing his scruffy visage. An online book published by the museum will help bring Owney’s story to a new generation.

“In history, we deal with humans and big events,” says Pope, “[so] to study and chronicle the life of a dog is really not something I signed up for when I started doing history work. And it’s just been tons of fun.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Arcynta-Ali-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Arcynta-Ali-240.jpg)