Pack Rat

First Virgil Johnson gave up smoking. Then he gave up his breathtaking collection of tobacco-nalia

At the height of the depression, a 15-year-old caddie named Virgil Johnson picked up some discarded cigarette packages from the grassy expanse of Washington State's Wenatchee Golf and Country Club. With brand names like Murad and Melachrino, the packs evoked exotic, faraway places; though empty, they still bore the pungent aroma of Turkish tobacco. That was the beginning. Later, as a chief petty officer and combat photographer on a battleship in World War II, Johnson found himself in Cairo, where he went on a buying spree, collecting all sorts of brands, including one depicting a languid woman draped over a lion, into whose face she blows a column of smoke that spells out the cigarette maker's name.

More than a half-century later, Johnson, 84, offered the fruits of his long obsession to the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, turning over about 6,000 cigarette packages, classified into 24 albums by manufacturer and country of origin from Afghanistan to Venezuela.

The collection, says Smithsonian curator David Shayt, "encompasses the vast acreage of tobacco history. What Virgil has done is to display the face of the tobacco industry as it presented itself to the consumer, in album after album, page after page, in a very organized, antiseptic and dispassionate way. He chronicles tobacco's rise and fall in a remarkably small space."

Johnson, who lives in Alexandria, Virginia, swore off cigarettes decades ago when he read about the Surgeon General's health warning (though he admits to an occasional cigar or pipe). He broke his vow of cigarette abstinence only once, to sample a pack of Southern Lights, a brand manufactured exclusively for state prisoners and sent to him by the Illinois Department of Corrections. The cigarettes, he concluded after a few puffs, "were a part of the punishment."

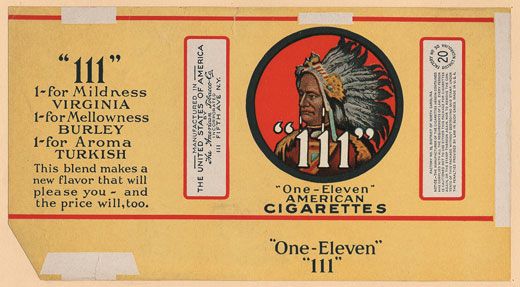

Over the years, Johnson became attuned to subtle and major shifts in cigarette advertising and packaging design. He points out, for instance, that Marlboros were marketed in the mid-1940s not for cowboy wanna-bes but for tenderfeet seeking "extreme mildness." The cigarettes even featured a "beauty tip," ruby-red edging at the unlighted end to better hide traces of a female smoker's lipstick. "The beauty tip didn't affect the taste at all," Johnson says, "but if you were a man and smoked the red-tipped ones, you'd encounter some raised eyebrows."

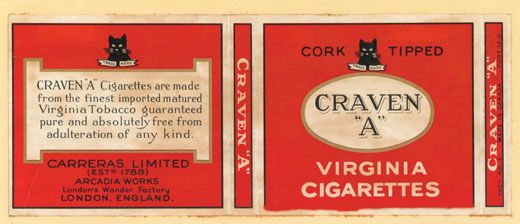

While cigarette manufacturers added lilac and rose perfume to attract female smokers, other additives were geared to both sexes. The Johnson collection documents cigarettes laced with rum, maple syrup, vermouth and honey. Lambert Pharmacal, makers of Listerine, once marketed a cigarette whose "cooling and soothing effect" was achieved by "impregnating fine tobacco with the antiseptic essential oils used in the manufacture of Listerine." A Coffee-Tone brand attempted to combine two early morning vices by marrying "the flavor and aroma of selected coffees with the finest domestic and imported tobaccos." Says Johnson: "At the time, the manufacturers probably weren't getting very good tobacco. The flavoring could kill the poor tobacco taste."

Johnson's collection also recalls the days when movie stars such as Barbara Stanwyck, Lucille Ball, Ronald Reagan and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., professed their devotion to Lucky Strikes or Chesterfields. An Algerian company featured Jean Harlow on their Star brand, and Head Play, an American brand, was named for the winner of the 1933 Preakness.

Postwar America saw the rise of Atom cigarettes with translucent tips banded in orange, green and gold, evoking the fluorescence of uranium. Politicians, including Presidents Eisenhower and George Bush the elder, were feted on election year packages. Some cigarette marketers even tried irony. A decade ago, Gridlock billed itself as "the commuter's cigarette." In 1960, "Philter" was true to its name: mainly a filter with only an inch of tobacco. "The world's most exhausting cigarettes," the package boasted, adding that "Philter smokers' butts are bigger."

Johnson says that package design became less elaborate in the 1960s, when fewer brands with Turkish tobacco meant less imagery beckoning smokers to foreign locales. "The new images weren't as colorful," he says. "The designs were more abstract."

In addition to the Smithsonian collection, Johnson also donated about 4,000 cigarettes to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for future research on tobacco and its uses. Sealed in glass vials, the cigarettes ensure that Johnson's lifelong avocation will not go up in smoke.