That Time When Ansel Adams Posed for a Baseball Trading Card

In the 1970s, photographer Mike Mandel asked his famous colleagues to pose for a pack of baseball cards. The results are as amazing as you’d imagine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/9b/8f9bad04-da57-4878-b4a0-b7732c862fe0/hero-baseball-photographer-cards.jpg)

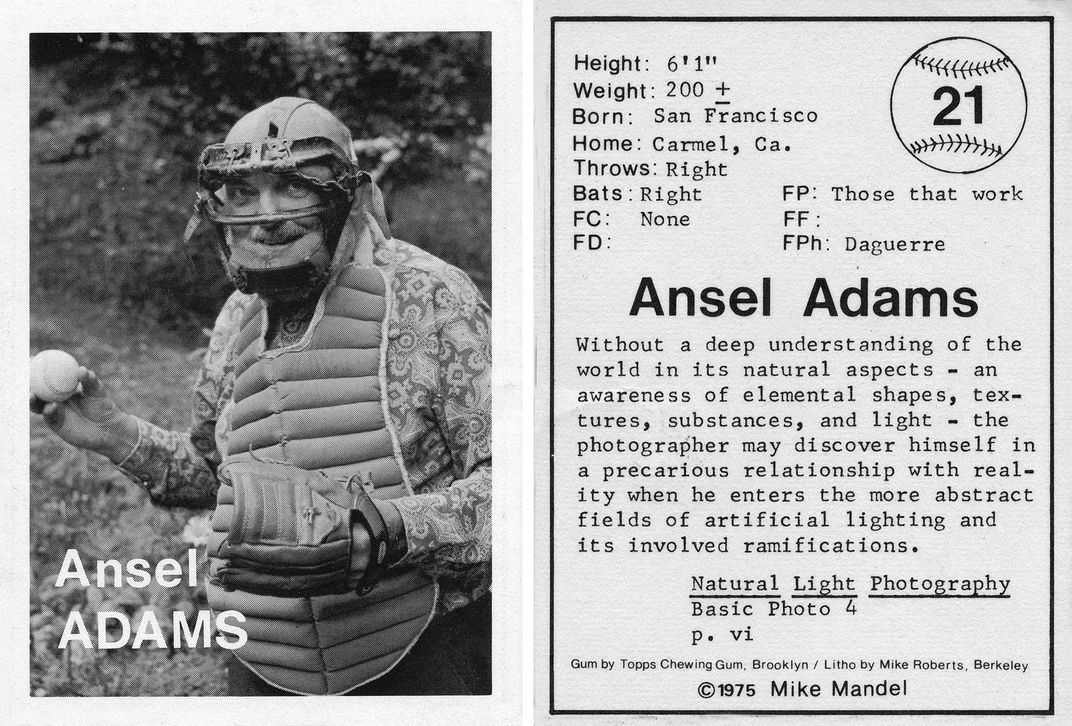

Forget that 1989 Ken Griffey Jr. Upper Deck card or your 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle, the real baseball card prize is the Ansel Adams rookie. How many of you can say you have that in your parents’ attic?

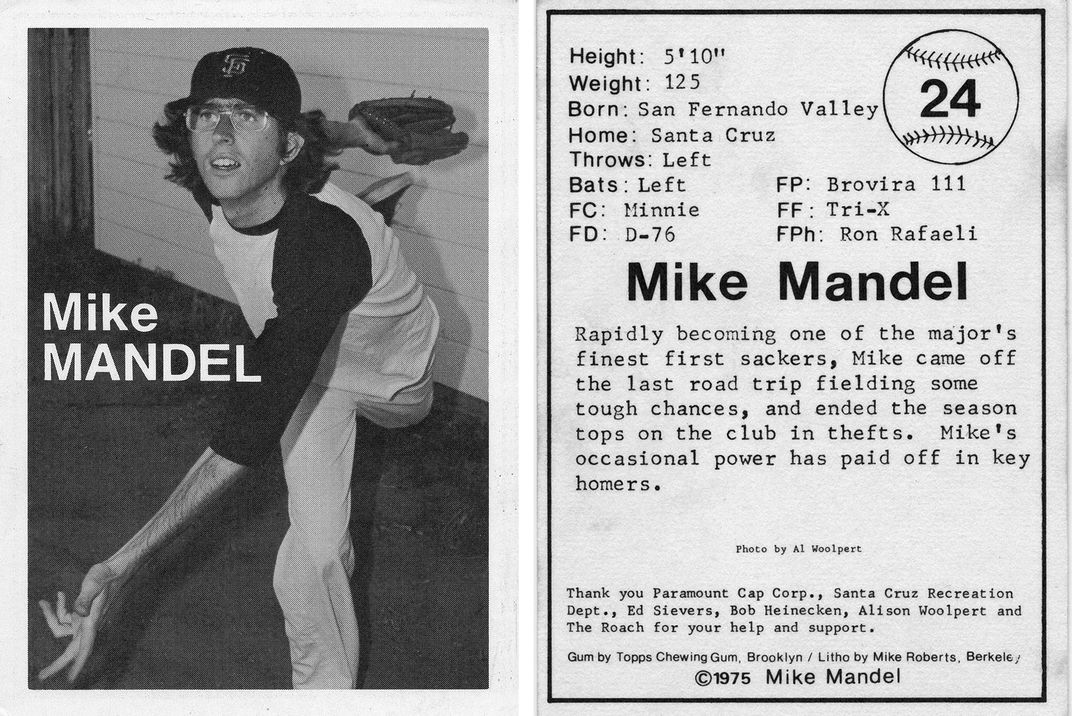

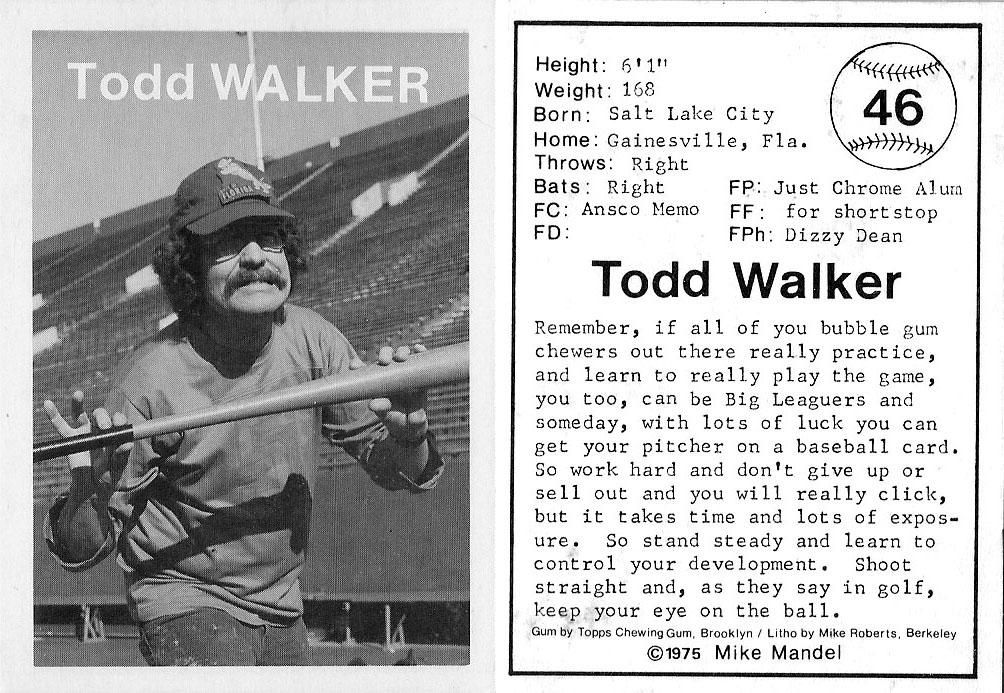

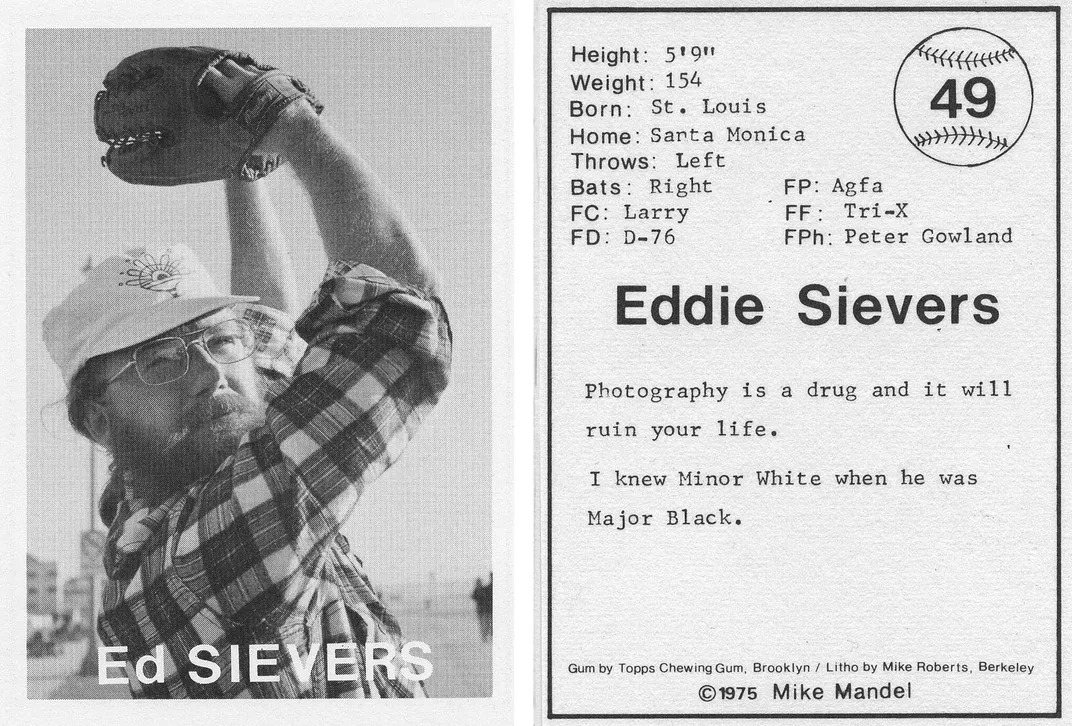

The Adams card is one of 135 cards in the “Baseball Photographer Trading Cards” set, a whimsical and unique collectible that’s equal parts art and spoof. It was the grad school brainchild of Mike Mandel, a photographer and professor at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and features images of 1970s photographers in baseball gear and poses. The cards are being reissued this fall by D.A.P./J&L Books as part of a boxed set of Mandel’s work called Good 70s.

Mandel’s maverick streak was evident early—at the age of seven while growing up in Los Angeles, he received a San Francisco Giants hat and transistor radio from his grandmother following her trip to Northern California. The Giants were fresh from their move from New York, and Mandel would lie awake, feigning sleep and staying up late to listen to Giants games on the radio.

“All my friends were Dodgers fans,” he says. “I was kind of the antagonist.”

Like many other boys of his generation, he collected baseball cards throughout his childhood. By the time he reached graduate school for photography at the San Francisco Art Institute in the mid-1970s, the country had changed dramatically—the scrubbed façade of the 1950s had been exposed by the counterculture movement, changing many facets of American society, including the art world. Up until that point, photography had been considered a derivative, sideline pursuit, the podiatry of the art community.

“There were very few photographers that were getting any kind of national recognition as far as artists go,” Mandel explains.

“Photography was always seen as this reproducible medium where you could make tens of thousands of photographs off the same negative, so it didn’t have that same aura of the original,” he says.

That lack of respect traces back to the early-20th century, when art theorist and philosopher Walter Benjamin “talked about how the art object had a very particular aura that was very specific. If you saw the original artwork in a museum it was really a very different kind of experience than seeing it reproduced in a book or some other way,” Mandel says.

“Photography was utilitarian,” says Shannon Thomas Perich, curator in the photographic history collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“Where there were famous photographers, they were photojournalists and war photographers—Margaret Bourke-White, those photographers that were featured in LIFE magazine, Robert Capa—even though you had lots of great photography coming out of the WPA [Works Progress Administration] and those photographs were very visible, photography was still very functional, and there wasn’t a lot of art photography that was seen widely,” Perich says.

But with the social foment of the 1960s, photography became a critical tool for depicting the injustices that fueled the decade’s outrage.

“If you go back to the ‘60s and the counter culture, you see images of the Vietnam War and recognize how photography was so important in communicating what was going on in the world,” says Mandel. That, coupled with vast improvements in the quality of 35 mm cameras, spurred a surge of interest in photography, especially in the academic community. Photography was finally taken seriously as art, and university art departments started churning out a new generation of photographic artists.

Sensing the shifting winds, Mandel wryly commented on photographers’ new legitimacy by combining their portraits with the ultimate symbol of commercialized Americana—the baseball card. With the help of his graduate advisor Gary Metz and Robert Heinecken, who established UCLA’s photography program in 1964, Mandel and his girlfriend at the time, Alison Woolpert, made a list of 134 photographers around the country who they wanted to depict in their set of cards.

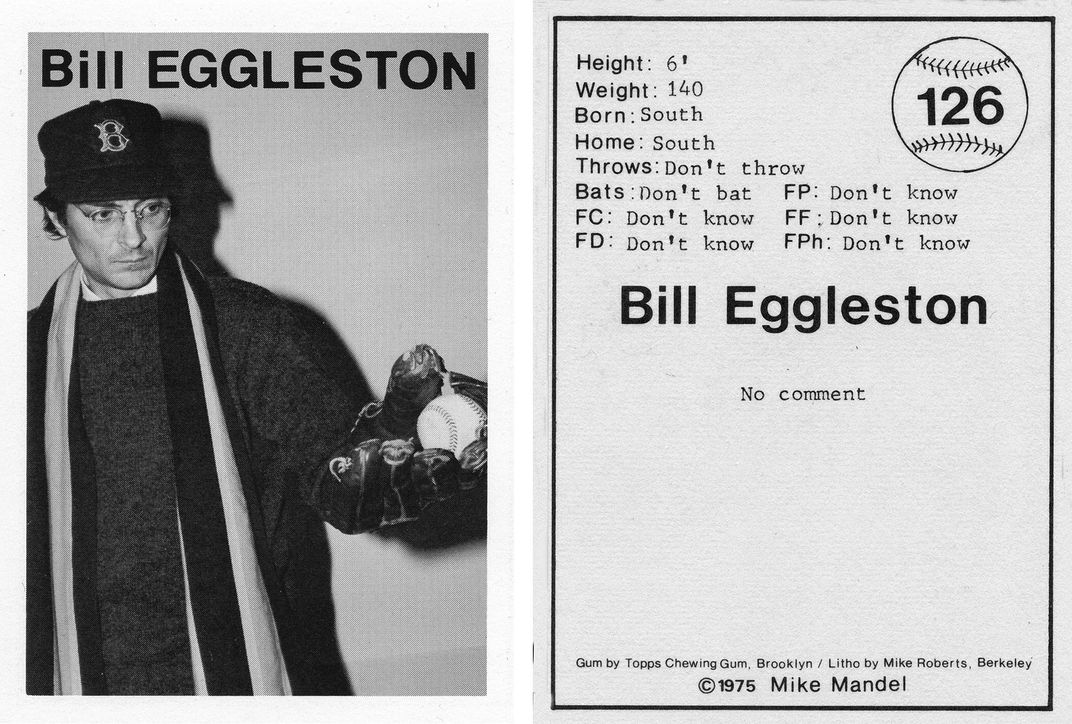

“I wanted to make fun of the fact that this was a double-edged sword. It was great that photographers were being recognized as artists and that they were getting long overdue recognition, but at the same time there was this other half that came with it, which is this popular celebrity-hood which keeps people from being accessible,” Mandel says.

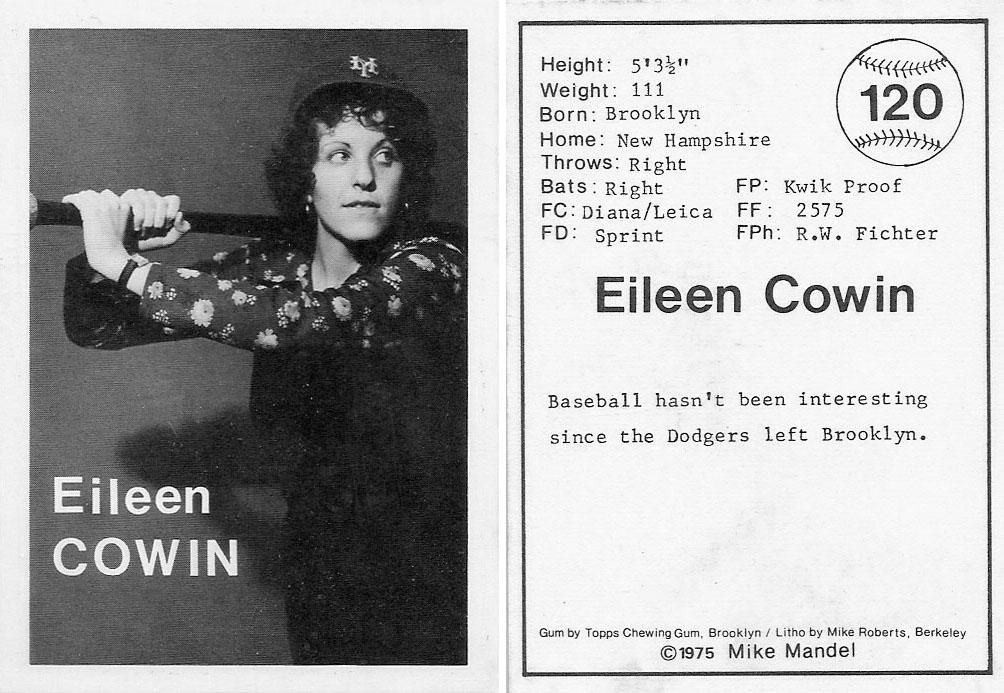

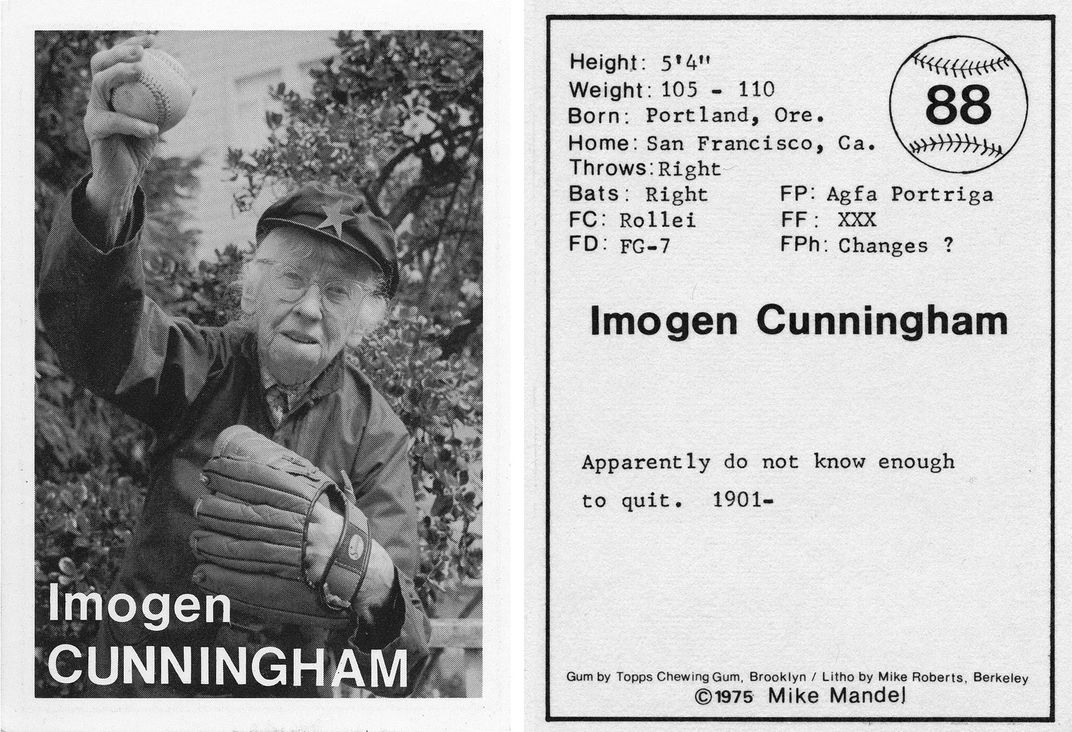

He started by approaching photographers in the Bay Area, landing such greats as Imogen Cunningham, whose card shows her throwing a nasty change-up while wearing what may seem like a Houston Astros hat but is actually a Mao cap, revealing her extreme political proclivities. Getting big names like Cunningham opened the floodgates, as other renowned artists like Ansel Adams signed on. Despite Adams’s celebrity, back then enlisting him in the effort was as simple as finding his number in the phone book and making a call.

“He thought it was a great idea, was very congenial and had a good time with it,” Mandel says.

Most of the artists he approached shared Adams’ enthusiasm.

“They were kind of making fun of themselves. They were in on the joke that photography was becoming a bigger enterprise, a popular cultural enterprise,” he says.

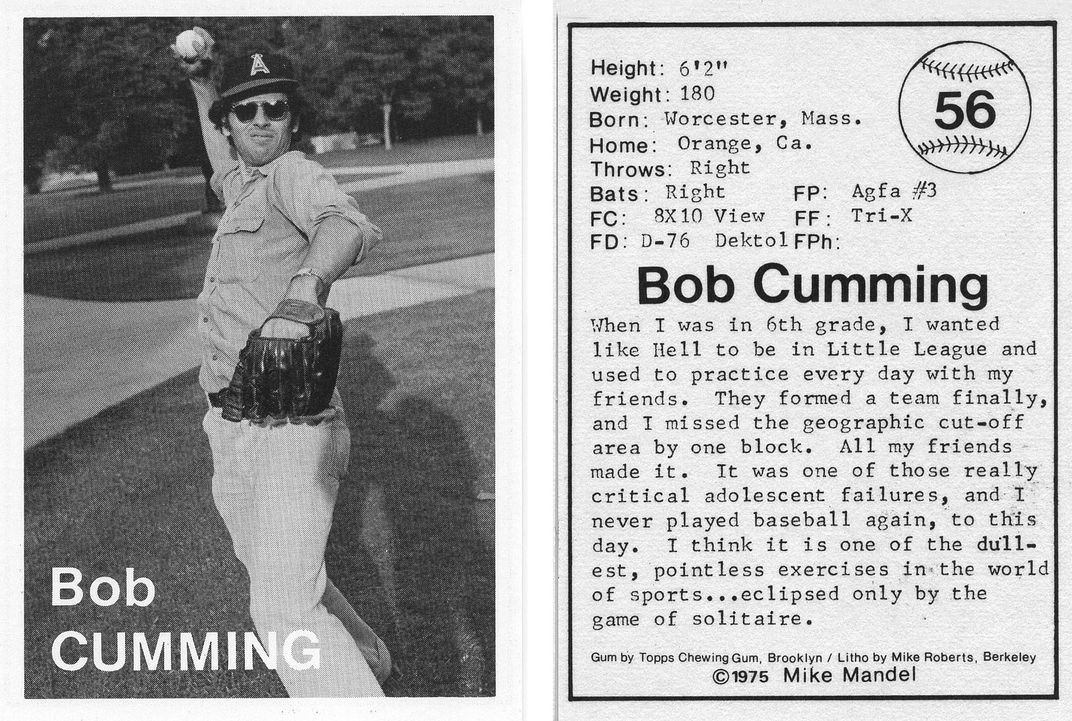

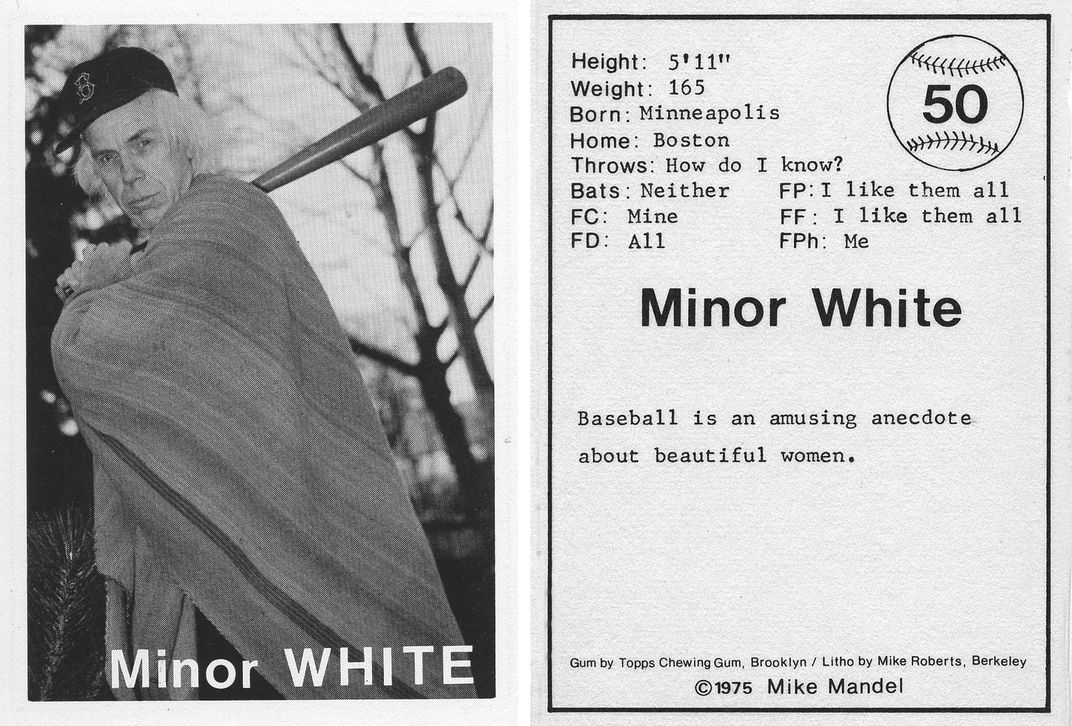

Mandel and Woolpert took their show on the road in the fall of 1974, cobbling together $1,700 in savings and embarking on a 14,000-mile cross-country road-trip to shoot their subjects. Once back, he took on the task of publishing 3,000 copies of each card for a total print run of 402,000. He carried his spoof to the extreme, including such vital statistics on the backs of the cards as “Favorite Photography Paper” and “Favorite Camera” and bits of wisdom from the photographers themselves (“Baseball is a an amusing anecdote about beautiful women,” said Minor White).

Mandel randomly sorted the cards into packs of ten and bundled them in plastic sleeves. The only thing missing was that key staple of all baseball card collecting—the bubblegum.

But Topps, the main manufacturer of baseball cards, gladly obliged Mandel’s plea for assistance, and before long his garage smelled like a cotton candy stand at the circus.

“I can’t recall how much it weighed, but I had 40,000 pieces of gum in these cartons that I stored in my garage,” he says.

He inserted one stick of gum per pack and distributed them to museums and art galleries around the country where they sold for a dollar apiece.

Coverage in Sports Illustrated, Newsweek and others generated such a buzz that museums began holding card trading parties where they could try and build complete sets. At one event at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Mandel held a card flipping contest, awarding the person whose card landed closest to the wall with a carton of 36 packs.

Given their popularity and limited run, the cards have since become a rare collector’s item. Mandel still sells original complete sets for around $4,000. But a much more affordable option is the re-issued set that comes as part of the Good 70s boxed set, for which all of the original negatives were re-scanned.

“The cards look ten times better in terms of their detail than what we had in 1975 in terms of technology,” he says. The set also includes reproductions of his other work from that era, some of it never-before-published, and a pack of the original cards from Mandel’s remaining collection. Just don’t try chewing the gum that’s included.

“I contacted the Topps people and the guy there in public relations remembered the guy from 40 years ago [who had donated the gum in the original project]. He inquired whether or not they had any gum because now they don’t even make gum except for some esoteric projects. They just make the cards. But he actually connected me to a guy in New Hampshire who makes fake gum from Styrofoam material. It’s pink, and it looks just like the gum from the packs of that era. We bought it from the guy and printed on the backside ‘this is not gum.’”

But keep your dentist’s phone number close, just in case your nostalgia gets a little carried away.