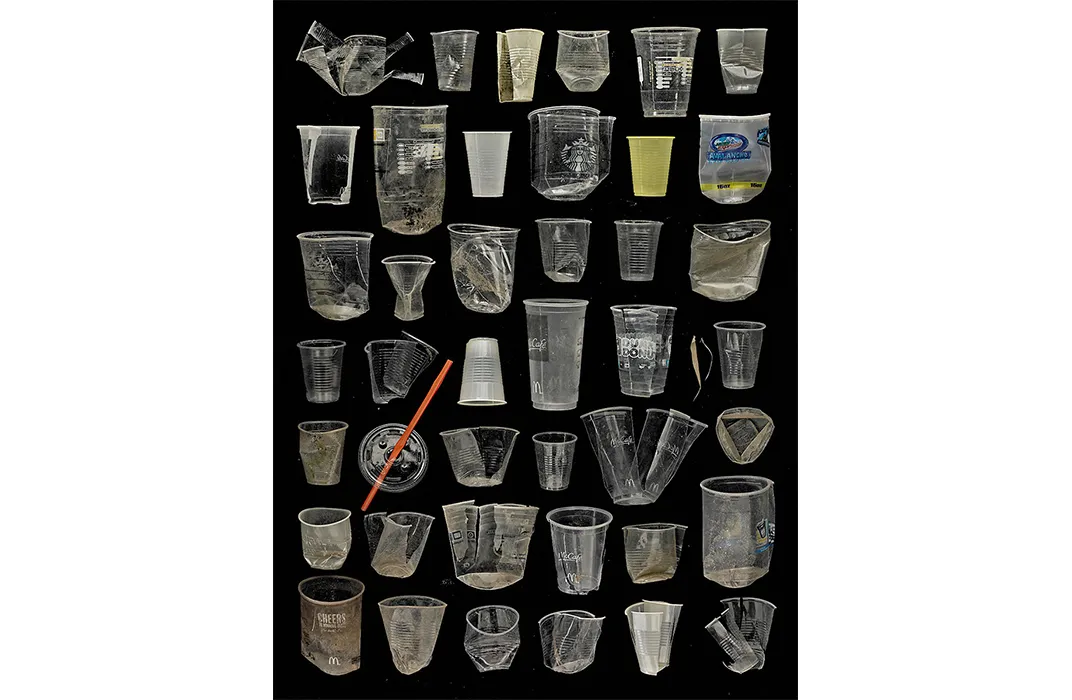

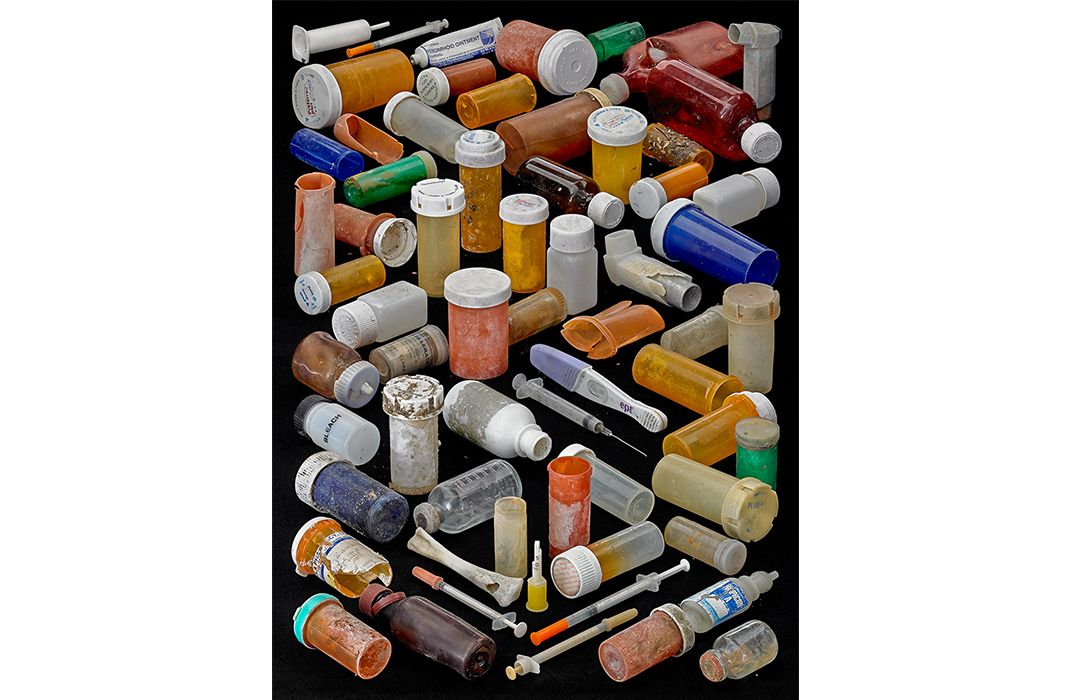

This Photographer Creates Fine Art Out of Trash We Throw Into the Environment

Barry Rosenthal obsessively collects washed up garbage along New York’s waterways and then assembles it into stunning but disturbing art works

Photographer Barry Rosenthal always regarded nature as a source of inspiration and beauty, but he never concerned himself with environmental issues such as pollution. Which is why, while combing natural sites around New York City for botanic specimens, he didn’t pay much attention to the garbage that inevitably crowded the weeds and wild flowers he collected to photograph.

That is, until he visited New Jersey’s Forsythe Wildlife Refuge on New Year’s Day 2007.

A storm had flattened all of the grasses—Rosenthal’s normal subjects—and deposited an extra heaping of plastic garbage in that otherwise pristine birding sanctuary. On an impulse, Rosenthal collected a few pocketfuls of plastic bottle caps, and then photographed them in the field using the method he normally reserved for plants.

He thought it would be a one-off experiment. But the next time ventured outdoors, he found that his eye was again drawn not to the plants but to the trash. “The plastic took on a greater importance,” he says. “It began to occupy more of my time.”

Now, more than six years later, he’s still at it. Rosenthal has since undertaken dozens of garbage collecting trips, mostly to marginal areas along the New York Harbor—to places such as Dead Horse Bay, Floyd Bennett Field and the wetlands that line the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. “I really would not call them beaches,” he says. “They’re not places that anyone would want to spend any time on.”

For Rosenthal, however, those trash-choked shores and ditches are endless resources, bringing in a new slew of garbage with each storm, high tide or rush hour commute.

All of that man-made waste degrades and threatens local ecosystems and wildlife. Birds, fish and mammals all have a tendency to mistake a piece of plastic as a tasty morsel, harming or even killing them. Beach trash like fishing line, plastic bags and six-pack rings can easily become tangled around fish, birds or turtles. And some trash—discarded batteries, half-empty oil and pesticide containers, electronics—can leach harmful chemicals into the water and soil.

Rosenthal collects opportunistically, picking up whatever strikes his fancy—three garbage bags’ worth of glass bottles one day, washed up straws, plastic cups and shell casings another—and lugging it all back to his studio in Brooklyn. There, he allows it to dry, but does not clean or alter it. “I want to tell the story of what’s out there,” he says.

Rosenthal is as meticulous about his garbage’s origins as he is about its eventual composition. He imposes strict rules on the project, politely refusing any “donations” from friends who stumble upon an interesting piece of trash. Like a monk atoning for the pollution sins of an entire metropolis, his collecting missions to the city’s foulest outposts stand in as his own mortification of the flesh rituals. “My orthodoxy is that I’ve got to be the one to collect it and haul it in,” he says. “I’ve got to do the whole process."

“I need the connection to the objects,” he continues. “Collecting itself is exciting and inspirational, and new ideas come from putting myself out in the field.”

To photograph the objects, Rosenthal built an approximately seven-foot-high stand that suspends his camera above an area up to 10x5 feet on the studio floor. He hooks the camera up to a monitor, which allows him to tinker with the layout without having to repeatedly climb up to look through the camera. The objects themselves, Rosenthal says, dictate their eventually composition, which he often toys with for a month or longer.

Once he’s shot a piece, he recycles most of the garbage (the oil bottles, for example, were leaking and creating a stench), but he also keeps some of it around for a future installation. As such, about a third of his 400-square-foot studio is now devoted to garbage storage. “Photographers are kind of neat about how they operate,” he says. “I have to put off that urge for neatness in order to tolerate piles of garbage in my studio.”

So far, he has shot about a dozen photos using this method. The series, which he calls “Found in Nature,” is only about a third of the way complete by his estimate. Some collections—the purples, reds and autumnal colors—are not robust enough to allow for their own photo yet, and he’s trying new angles, such as vertical installations. Rosenthal’s urge to collect and to assemble, too, has not yet been satiated. Collecting, he says, “is just part of me.” Over his life, he has collected toy horse carnival prizes, State plates and cast iron pans, but for now the garbage has become center stage.

That garbage, he says, has changed him. Eventually, it became impossible to ignore the implications of all of that endless human detritus. “I didn’t start out to do anything environmental, but I’ve been politicized by this,” he says. Manufacturers, he now thinks, should be obliged to take back their used products for recycling, and consumers should, of course, stop throwing their trash into nearby lakes, rivers and oceans.

Rosenthal is not the only artist to be inspired and politicized by marine debris. Last year, for example, an international team of artists and scientists joined forces on a garbage-collecting expedition along the Alaskan coast. As the artists gathered floating fodder for their future works, the scientists onboard briefed them on what those bottles, nets, bags and cans meant for the environment. The creations inspired by that trip are now on display at the Anchorage Museum.

As for Rosenthal’s work, people seem to like his images, he says, but he wants them to come away with more than just an impression of pretty pictures. Instead, he hopes his work inspires them to contemplate the implications of all that junk for the world’s oceans—a problem whose magnitude society is just beginning to grasp. Indeed, the last month or so has seen coverage of ocean garbage obscuring the search for the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370; scientific claims that the ocean floor is turning into a massive landfill; and evidence that Arctic ice contains trillions of tiny pieces of plastic frozen within it.

“This stuff doesn’t just go away,” Rosenthal says. “It’s in the environment forever.”

Rosenthal plans on publishing a book and hosting a solo exhibition of “Found in Nature, upon completion of the project. Limited edition prints and pop-art-style glasses with his artwork printed on them can be purchased through his website.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)