This Photographer Shoots Sharks to Save Them

When he’s not creating movie posters, Michael Muller swims among the oceanic predators, capturing stunning images

Michael Muller is a legend in Hollywood. His work is seen by millions of moviegoers each year, though most of them probably don’t know who he is. Muller is one of the preeminent movie-poster photographers in the business. This year alone, Muller’s artistry can be seen in the promotions for X-Men: Apocalypse, Captain America: Civil War and Zoolander 2. He was also responsible for the hazy Wes Wilson vibes of the poster for Inherent Vice and the action-packed Guardians of the Galaxy one, among dozens of other memorable advertisements. When he’s not photographing Hollywood’s biggest names, however, Muller finds himself drawn to the big predators of the oceans: sharks. His startling, intimate portraits of these beasts of the oceans have more to do with his action heroes than one might think.

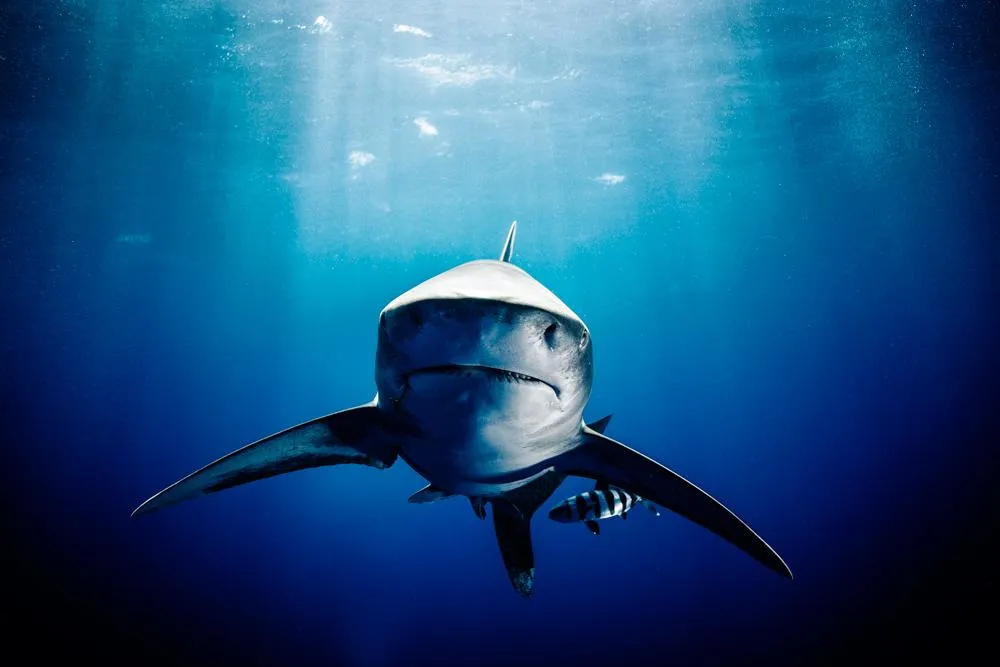

“I want to light a great white like I light Iron Man,” Muller recently recalled thinking. Sharks have interested Muller since childhood, but it wasn’t until 2007 that it occurred to him to photograph them. He quickly found himself in awe of the animals and determined to use his talent to help spread a message of respect and conservation. “I’ve sold $14 billion in movie posters and Nike and Range Rover, all these huge companies. Maybe I can sell our planet,” he says he thought to himself. “Maybe I can sell these animals in a way people haven't seen before.”

All he had to do first was grow comfortable swimming with sharks without a cage, get his studio team diving certified, and invent an entirely new system of underwater lighting. In a conversation with Smithsonian.com, Muller described the challenges, the successes, and the close calls of his passion project, Sharks, that is now available as a book and is on view at Taschen Gallery in Los Angeles.

Your book has this great anecdote about your first shark photograph. What happened?

It was roughly fifth grade, I was ten years old. We were living in Saudi Arabia because my father got transferred over there. His hobby was photography, so my first camera was a Minolta Weathermatic, a little, yellow waterproof camera. We got National Geographic at the time, and I stumbled across a photo of a shark, took a photo of that photo, and got the film processed.

All my buddies were at my house and I broke out the package of prints and said, "Check out this shark I shot in the red sea." They were all like, "No way! You saw a shark!" But the guilt started eating at me so I fessed up that I'd taken a photo of a magazine and we all got a laugh. But that definitely had an impact on me and stuck with me, the power of photography, to see the impression it had.

When did you begin taking your own photographs in earnest?

We came back to America in time for me to start the 7th grade. Shortly there after I started shooting snowboarding, which was at its inception. My best friend from high school got his college tuition from his dad and we made the first-ever snowboarding calendar. Throughout the year I was also shooting all the rock bands that came to town. I would call up Warner Bros. and say, “Hey I need to shoot U2 for the Such-and-Such Times.” I would get a photo pass and I'd go shoot all these bands and become friendly with them and meet the labels. And on a side note, I was doing triathlons. I was fifth in the world and I raced against Lance Armstrong. When it came time to graduate high school, I left the day I graduated and moved to San Diego, which was sort of the epicenter of triathlons, and after about six months I asked myself what do you want to do? Do you want to be a professional triathlete and swim, bike, and run for the next ten years or do you want to do photography?

I chose photography, thankfully. I moved to Boulder, Colorado, with my friend Justin Hostynek. We both got free snowboarding passes because we were photographers and did 120 days on the mountain. But then another friend of mine, a musician, was in Los Angeles and said, "Move to L.A.!" I taught Justin what I knew about photography and he stayed in Boulder, continuing to shoot snowboarding, and became one of the best snowboarding photographers and moviemakers in the business.

And I came to L.A. and started shooting actors and models and musicians. I sort of self-taught, and learned how to try out different films and find my style shooting models and actor friends of mine. It was definitely the right place at the right time. My first two non-snowboarding pictures were of Balthazar Getty and David Arquette. Leonardo DiCaprio and Drew Barrymore and all these young actors hadn’t gone on to become superstars yet, and this was before the Internet, before cell phones, before publicists. So I would go out and be like, "Let's go take pictures!" I started shooting these friends, Leo and different people, and then got an agent and started shooting for magazines and the rest is history.

Did you ever think about photographing sharks back then?

No, never. Jaws had a huge impact on me, scared the [expletive] out of me. Northern California, the Bay Area, it's a shark mecca. There are a lot of great whites there. You'd be surfing and the sharks would show up and eat a seal, and everyone would get out. Then two hours later, everyone would get back in and keep surfing. Sharks were on everyone's minds.

In the back of your mind as a surfer, you're always a little scared of sharks, but it never came into my mind to shoot them until 10 years ago. I was shooting all the Olympic swimmers for Speedo and I said, "I want to go shoot great whites. I want to go on a shark trip." My wife heard me, and for my birthday got me one of those cards, "Good for one shark trip." I called the next day and booked my travel. I was with ten people I didn’t know and I was the first in the water. I saw a great white coming out of the darkness and I locked eyes with it and I was like, "I see you, you see me, you're not this eating killing machine I thought you were." I was hooked from that moment on.

So on that trip you had this moment of realization and decided to start shooting sharks. How did you conceive of this project?

I came back from that trip and started thinking about lights. At the time, I was shooting for Speedo, I did that for eight or nine years straight, so I had tried every underwater lighting apparatus that was on the market, and I wanted to bring a studio underwater to shoot sharks, but I couldn’t. But I’m like, “I can't bring the shark to the studio, it'll be dead, so I’ve got to bring the studio to the shark.”

I went on a quest looking for lights, but they didn’t exist. There were 400-watt strobe lights, which everyone uses. And then there were big underwater HMI lights that require generators that James Cameron and those guys use for movies. But there was nothing for me. So I set out to invent them.

Then I met this guy Erik Hjermstad who fabricates housings for surf photographers and he was convinced he could make the lights. He brought in a guy from the Jet Propulsion Lab, and an old school dive photographer, and between the four of us we came up with the solutions needed to take hot studio lights under water. When I was heading to the Galapagos, for a work trip, the lights arrived the day before the shoot, and that was the trip that changed it all.

That’s almost the thing I'm most proud of. It’s funny, when I talk about it, people are like "You swim with sharks with no cage?" And I’m like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, but I invented a light that didn't exist!” I have patents on it. That was more gratifying because how many people invent a new lighting system in this day and age?

Does your family worry about you when you do this?

I think they did. But my wife came on a great white trip with me. She was crying the whole way, thinking it was the most irresponsible thing and we were going to die. We got out there and on the first or second dive we were hanging out of the cage and her perception completely changed. I thought she was going to jump on the back of a shark and swim away.

I have three daughters and they have watched me for ten years: I leave to go swim and shoot sharks and come back a week later with all my fingers and no shark bites, telling them how amazing the trip was and how the sharks are not there to attack daddy. Over the course of the years they learned what I didn’t at that age, they learned that sharks aren’t killing machines.

Do you work with shark specialists or other shark photographers or videographers?

I bring my assistants from my studio. I said, “Listen guys, I'm starting this project and either I’m going to use shark guys or you guys get certified to dive and come with me on this journey.” And they all jumped aboard. It's a real tight knit crew.

A couple of years ago I went to try to document a great white breaching at night. I was put in touch with this guy Morne [Hardenberg]. I shoot, he films. I came out to South Africa and we got skunked with the weather. It was rainy and stormy, and we were out at sea and we started talking.

About 10 years ago I was watching a shark documentary on television and I'm like, “Who is that guy filming with his back to the sharks, who is getting no glory. Who's the cameraman? That's the guy I think is cool.” So cut to me sitting on a boat in the pouring rain with Morne, and we start talking, and I'm like, “You're the guy! You're the one that was filming!” He's like "Yeah. And there's some guy in L.A. named White Mike that does –” And I'm like, "That's me! I'm White Mike!"

From that moment on it was like meeting my wife. We were instantaneously bonded. 10 months later I came back. We had five days and we got breaches every day, normal [day-time] breaches, three to four, maybe five a day, which is a lot. But when a great white breaches, there's no warning. You have to sit in the back of the boat with your camera up to your eye in rocky conditions, following this fake decoy seal that's going to the right and to the left, and then all the sudden out of no where, a shark goes “boom” and hits it. You literally have to just have your finger on the trigger and be ready.

We were going out at nighttime so we were leaving at 3 o’clock in the morning. When you're trying to track a black decoy seal in a black sea at nighttime with no light on it, the difficulty level goes up a hundred fold. We had spent four days, got nothing. We captured it on the last day.

What's the toughest part about photographing sharks? Their environment or their behavior?

The combo. You're dealing with wild animals and you're dealing with weather conditions that you can’t control. You're going out to places where sharks are in certain areas at certain times of the year, but there’s no guarantee. So you go there and you put the fish in the water and you wish for the best. I have been really blessed. If I didn’t get the shot I was after, I got something else. Mother Nature's got my back because of my purpose being out there.

I was sitting in the Galapagos on that boat and I visualized it. I saw a shark coming out of light and someone going, “Whoa look at that!” And then they turn the page, and you educate them and they go, "What? They're killing a hundred million sharks every year?” People have no idea. Then you point them in directions to help. That’s the goal: How can I use my gift as a photographer to get the message out there?

Have there been there any close calls with the sharks?

As far as close calls, probably the most dangerous thing was that happened or came close to happening was dive-related stuff like running out of air, almost being electrocuted, a light blowing up, that type of thing.

One close call was two or three years ago, we were swimming with great whites, and this 15-foot male shows up. We like to interact with what we call players; it's usually a girl and they're as interested in us as we are in them, and they’re very mellow. Sharks are just like people; they have personalities. And each species is different too so the sharks are different within their species.

With great whites, the boys are just like you would think young boys are: feisty. So this boy shows up, Morne did a dorsal ride, and the shark swam around us and did a couple of circles and a couple passes. On its last pass, it swam like it was going to go by me, but at the last minute, its head shot towards me, and I ducked down really quickly and hit it on its side gills, and it swam away immediately.

That's the other thing, no other species in the ocean, except for killer whales, swims towards a great white shark. Everything swims away from it. So they're smart enough to know that if all the sudden there's something swimming at it, it says, “Oh this is a predator,” and it swims away. A couple of years ago I’m out of the cage and I’ve got a great white coming at me. It’s going 35-40 miles an hour and it’s coming straight at me. That's how they get their prey. They hit it so hard that it knocks it out and then they go after it.

I've got this shark coming at me, full bore, I'm looking down at it, holding my camera, and off my right shoulder Morne comes off and goes straight at it, holding his camera, which has two lights on it, and goes straight at this 18-foot great white. All of the sudden, the shark does a 180 and turns off. I learned in that moment, that's how you handle a great white when it’s coming at you

Is there any one image that represents this project?

Out of every image, the message, the whole point, is in the image where you see my daughter in the cage and [a member of my team] face to face with a big great white. That shot encompasses it all. Here's a big great white with a guy who has no protection, he's not even holding a camera, and my daughter's inside the cage looking towards them. That shot transcends and gets the message across. It shows how we don't need to be afraid of these animals the way we've been programmed to be.