The Photographer Who Ansel Adams Called the Anti-Christ

William Mortensen’s grotesque, retouched photos of celebrities were a far cry from the realism favored by the photography elite

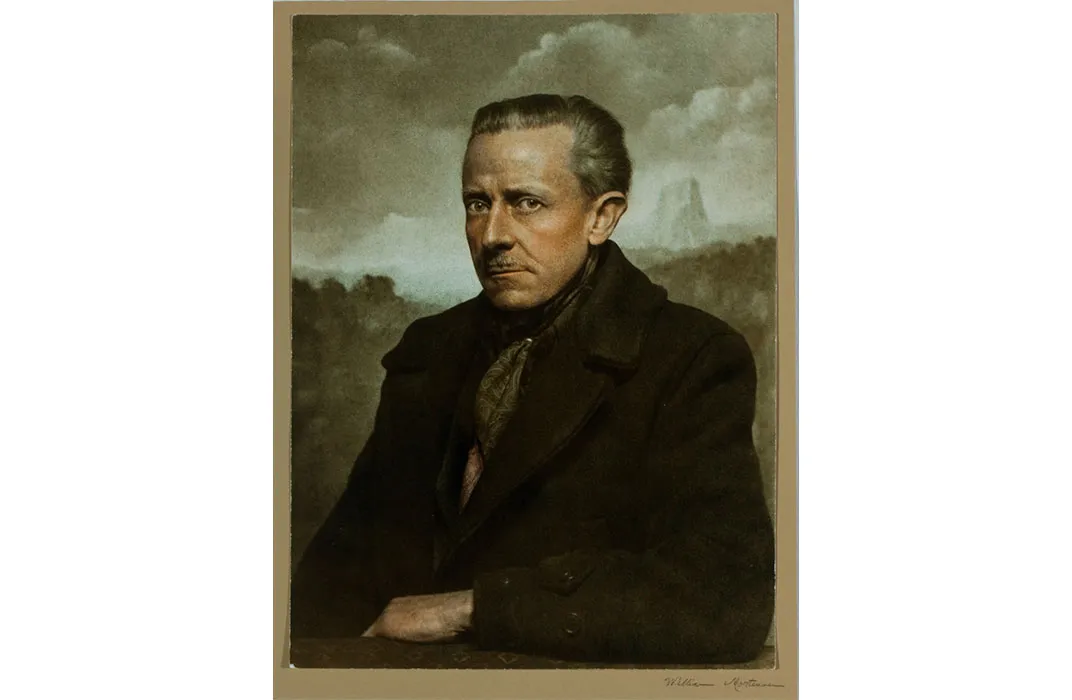

In 1937, the photographer Edward Weston wrote Ansel Adams a letter noting that he had recently "got a beautiful negative of a fresh corpse." Adams wrote back expressing his enthusiasm, saying, "It was swell to hear from you—and I look forward to the picture of the corpse. My only regret is that the identity of said corpse is not our Laguna Beach colleague." The "colleague" Adams referred to was William Mortensen, one of the most popular and otherwise respected photographers of the 1930s, whose artistic techniques and grotesque, erotic subject matter saw him banished from "official" histories of the art form. For Adams, Mortensen was enemy number one; he was known to describe him as "the anti-Christ."

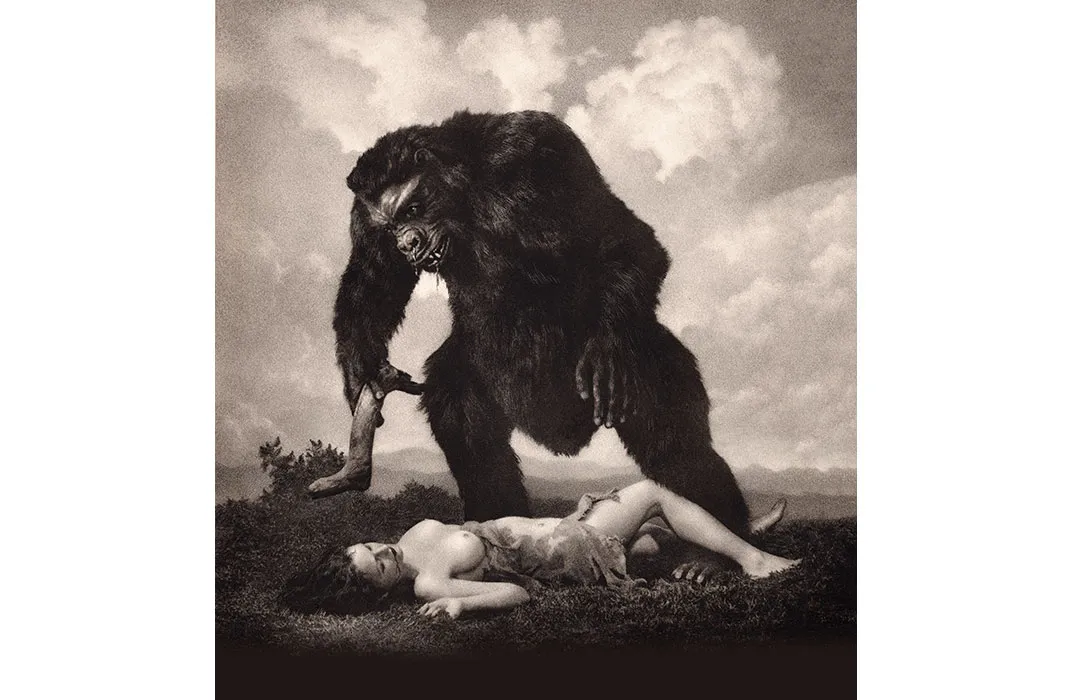

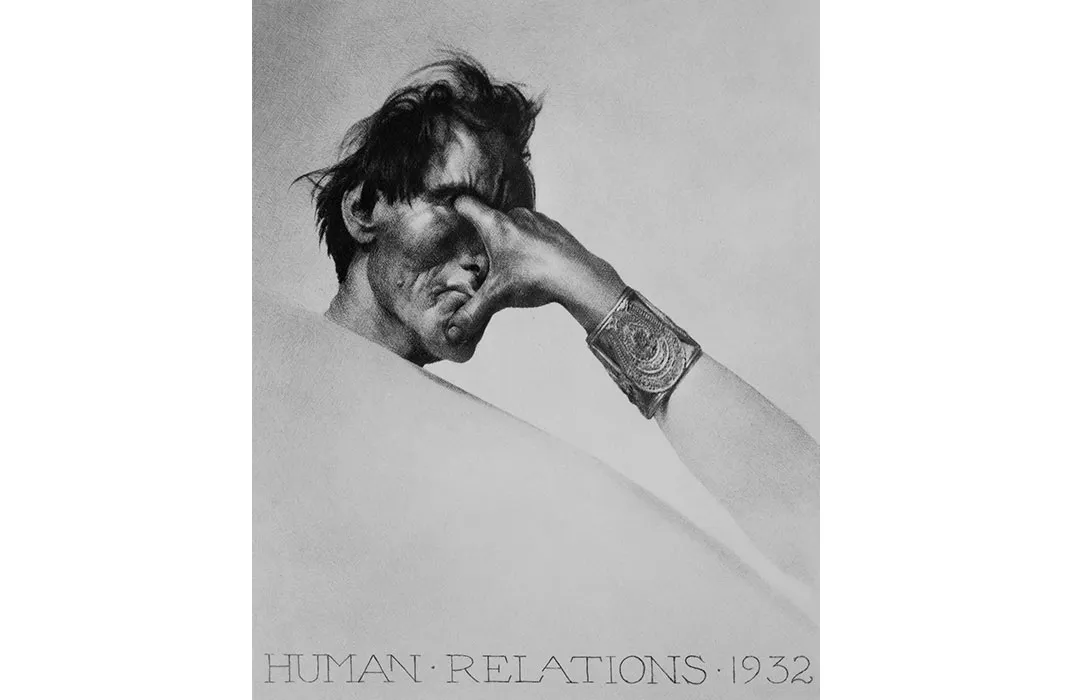

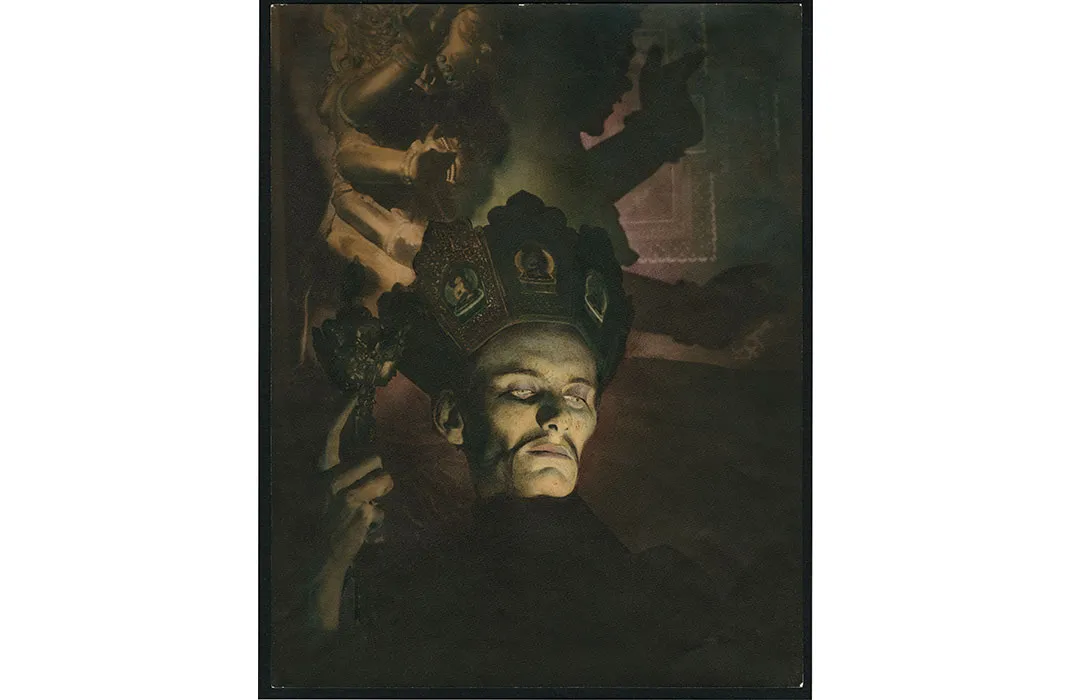

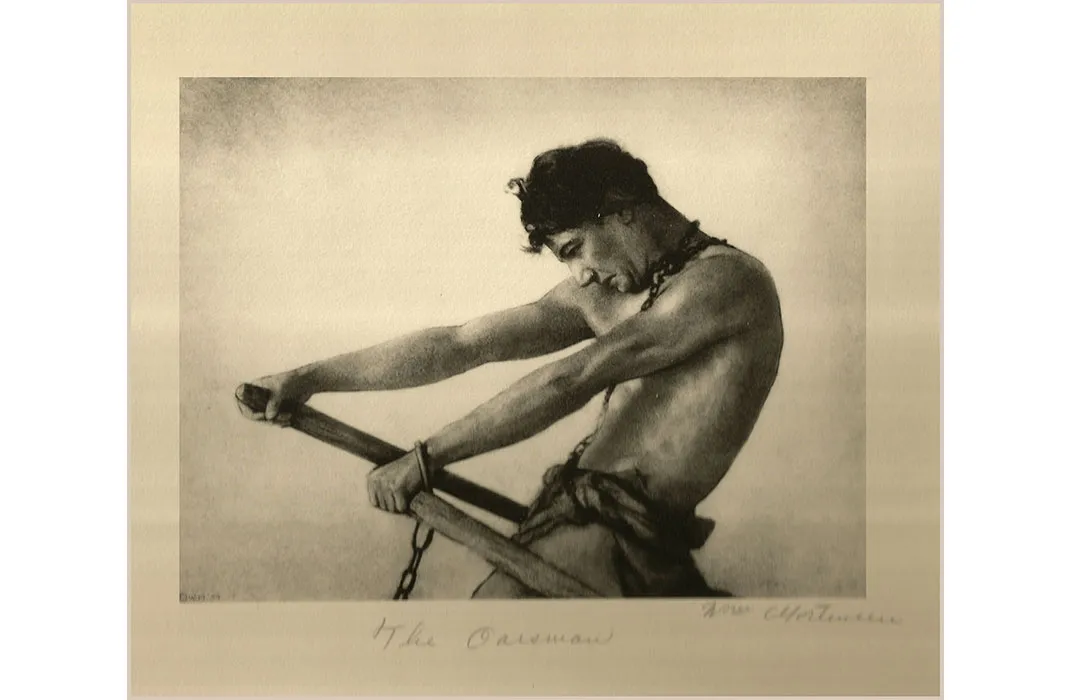

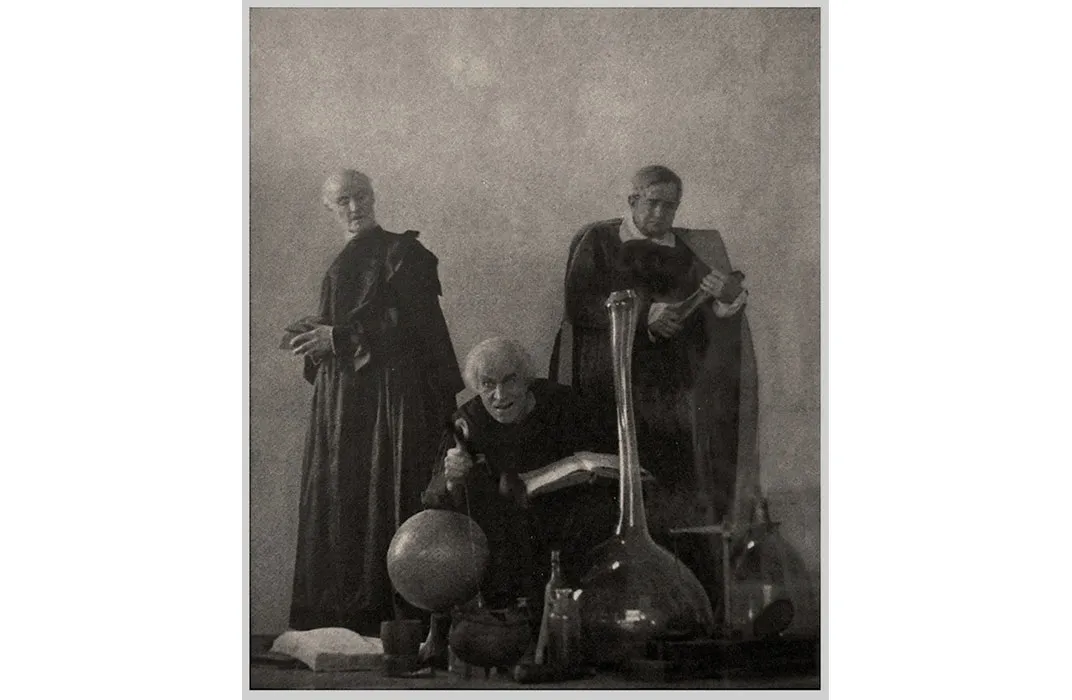

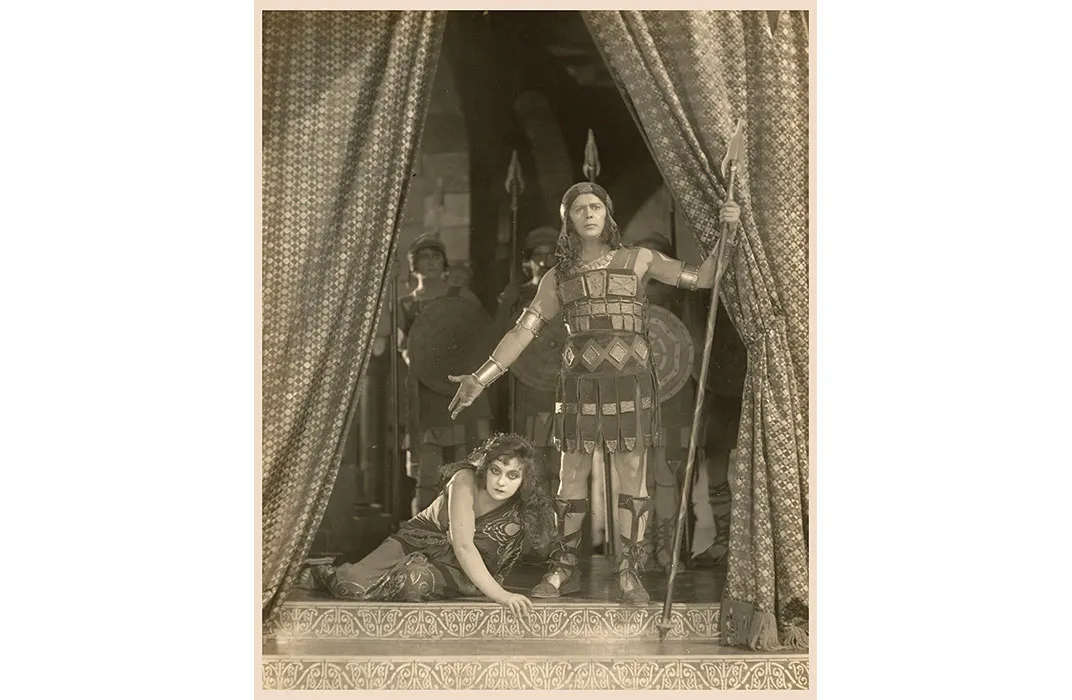

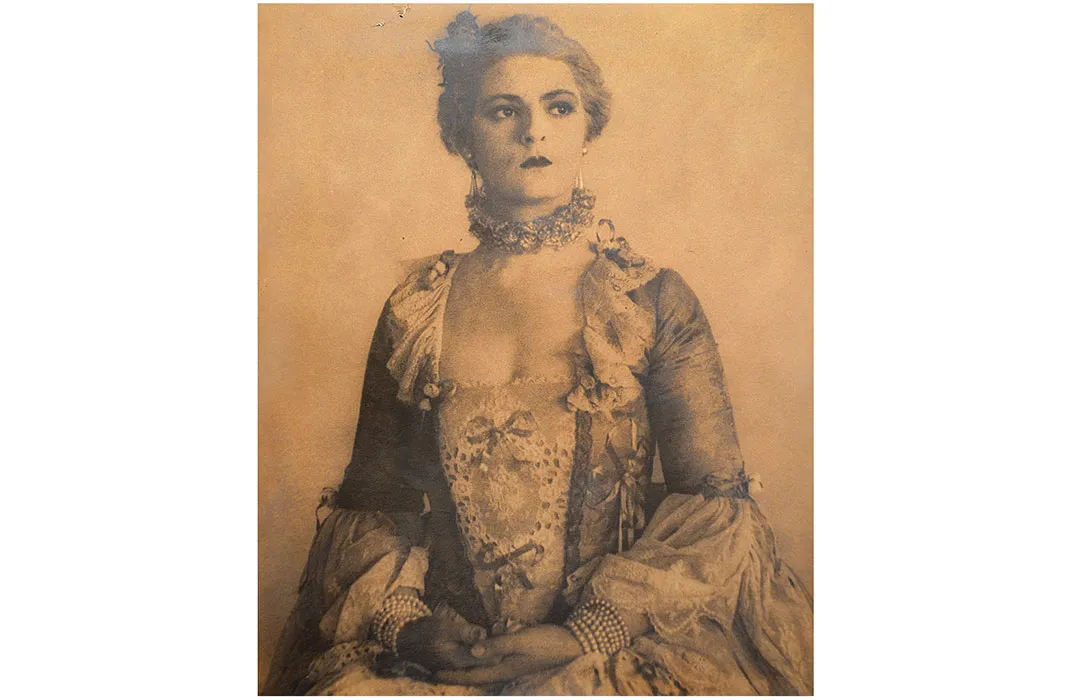

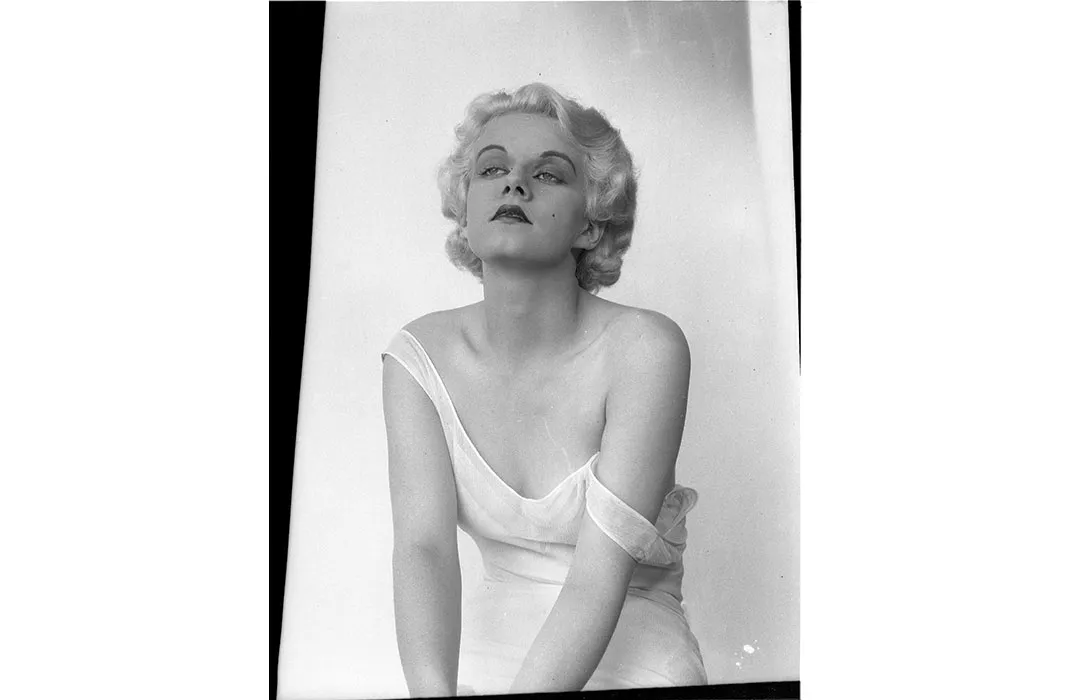

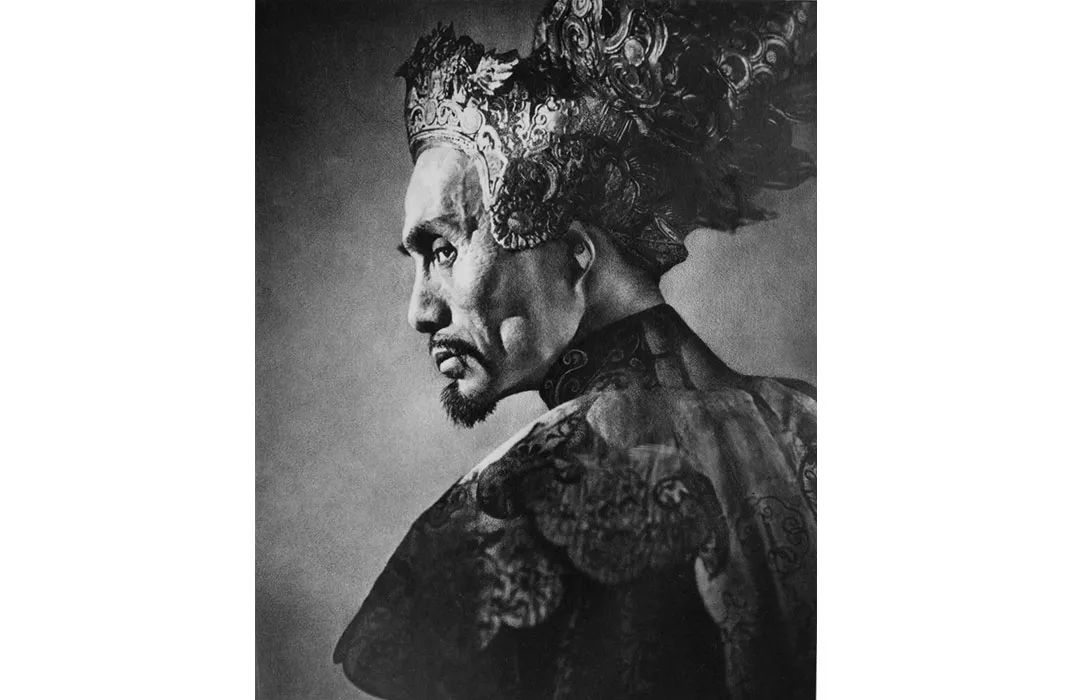

Born in Park City, Utah, in 1897, Mortensen studied painting in New York City before World War I, then moved to Hollywood in the 1920s, where he worked with filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille and shot portraits of celebrities Rudolph Valentino, Fay Wray, Peter Lorre, Jean Harlow and others, often in historical costume. He also created more abstract portraits of anonymous models, interpreting historical or mythological characters such as Circe, Machiavelli and Cesar Borgia, and shot images of witchcraft, monsters, torture and Satanic rituals, rarely shying away from nudity or blood. Despite his outlandish themes, between the 1930s and 1950s his images were widely shown both in America and abroad, published in magazines including Vanity Fair, and collected by the Royal Photographic Society in London. He wrote a series of bestselling instructional books and a weekly photography column in the Los Angeles Times, and ran the Mortensen School of Photography in Laguna Beach, where some 3,000 students passed through the doors. The artist and photography scholar Larry Lytle, who has done extensive research on Mortensen, calls him "photography's first superstar."

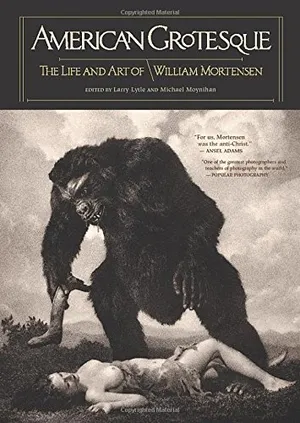

Yet Mortensen has been left out of most retrospectives and books devoted to the history of photography until relatively recently. In the late 1970s and 1980s, his work was rediscovered by the photo critic A. D. Coleman, and the collector, curator, and writer Deborah Irmas. Their work has helped bring Mortensen back to popular attention, an effort that seems to culminate this fall with gallery exhibits in New York, Los Angeles and Seattle, as well as the release of a major book on Mortensen. American Grotesque: The Life and Art of William Mortensen (Feral House) features previously unpublished images alongside essays by Lytle, the writer and musician Michael Moynihan, and A.D. Colemen. Feral House has also republished Mortensen’s instructional book The Command to Look, in which he analyzes his process and technique, offering tips about how to arrange compositions and create maximum impact.

Mortensen has been described as one of the last great practitioners of pictorialism, a late 19th/early 20th century movement developed by Alfred Stieglitz and others that championed photography as a fine art. Pictorialists were inspired by other art forms, including paintings and Japanese woodcuts, and emphasized an appeal to emotions and imagination rather than strictly accurate representation of reality. They embraced labor-intensive techniques: coating the surfaces of images with pigments and emulsions, scraping it with razors or rubbing it with pumice stones, and other manipulations that created a diffuse glow and impressionist softness. (Mortensen, however, disdained too much softness in his images, calling some of the pictorialists "the Fuzzy-Wuzzy School.")

Mortensen was also particularly interested in the psychological impact of an image, much more so than any other photographer of his day, according to Lytle. "He was interested in Jungian psychology, particularly the collective unconscious and archetypes," Lytle says.

Carl Jung believed that we all share a layer of unconscious memories formed by our earliest ancestors, which is why many of the same images and ideas, or archetypes, resonate throughout the world. This interest in psychology influenced both Mortensen's choice of subject matter and his composition: In The Command to Look, Mortensen argued that images should be constructed along certain patterns (the S-shape, triangle and diagonal, among others) which activated the brain's primitive fear response, and that this initial alarm should be followed up with subjects that appealed to three basic human emotions—sex, sentiment and wonder.

Many of his images of the grotesque combine all three. Asked why he was so interested in the grotesque, Lytle explains "[H]e was drawn to the very old tradition of the grotesque as it was used in European art and updated by way of cinema. He realized that photographers, particularly in America, shied away from the subject and he felt that it was an undiscovered territory of photography." Mortensen himself said that the grotesque had value for "the escape it provides from cramping realism."

Ansel Adams, however, favored realism, as did many of his famous peers, such as Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston. Collectively referred to as Group f/64, they became known for producing sharp, high-contrast, "straight" or "purist" photography, and disdained borrowing techniques from painting and other art forms to manipulate photos the way Mortensen did. According to the critic Coleman, Mortensen's disappearance from photography history is a direct result of his disagreement with Group f/64. Friendships between the members and prominent photographic historians (such as the husband-wife teams of Helmut and Alison Gernsheim and Beaumont and Nancy Newhall), Colemen says, ensured that Mortensen was left out of retrospectives and books. According to Lytle, "There are other references in letters between the Newhalls, Adams, and Weston that leads one to believe that they actively hated him. Mortensen represented the old order, and they felt that he was stymying their efforts to create a new basis for photography."

In turn, Mortensen called the work of "purist" photographers "hard and brittle." In a popular five-part series in Camera Craft magazine called "Venus and Vulcan: An Essay on Creative Pictorialism" (reprinted in American Grotesque), he wrote "'Purity' is conceived to consist in limiting photographic expression to the mechanically objective representation that is inherent in the uncontrolled camera … [but] Imagination is a wayward and willful wench, and when she is on the loose she is not to be held in check by any arbitrary boundaries that divide one medium from another."

Yet there may have been other reasons Mortensen lapsed into obscurity. "Long before Mortensen's death in 1965, his invented grotesques had been replaced by real grotesques, such as the horrifying war images that were widely reproduced in news magazines, as they still are today," Lytle writes in American Grotesque. "Mortensen's photographic representations of monsters and horrors began to look quaint when viewed against the real acts of barbarism and cruelty that were going on." Lytle also notes the influence of magazines like Life, and says that after the 1950s, "Photography as practiced by amateurs and artists became more photojournalistic, documentary." That left less room for the flights of fantasy and artistic manipulations that Mortensen so enjoyed.

Now, the time seems right for Mortensen once again. "Amateur photographers" (a class that today includes everyone with a smartphone) can add painterly effects of the type Adams disdained at the click of a mouse or the press of a touchscreen. And we’re surrounded by images of the unreal, from fantasy movies to video games. "I think the highly manipulated nature of his imagery is what everyone is now doing," Lytle says. "He predicted the imagery and thinking of 21st century photography."