Photographs of America’s Eastern Treasures Finally Have Their Moment in the Limelight

A neglected period of American photographic history goes on display at the National Gallery of Art

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/1d/e31d8653-6822-4cfd-8084-8f7259198f5e/3960-138.jpg)

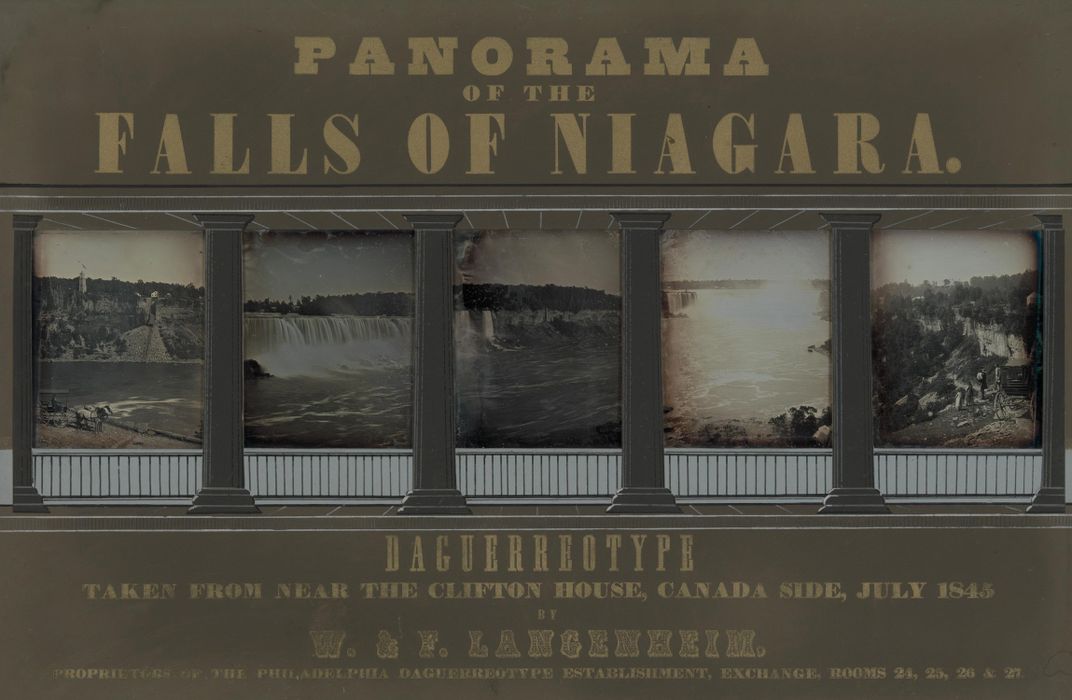

One of the first-known photographs of Niagara Falls looks fragile and faded. The silvery photo of the thunderous falls, captured by British chemist Hugh Lee Pattinson in 1840, sits within a glass case at the National Gallery of Art, just one floor below Frederic Edwin Church’s majestic Niagara. Despite not being nearly as entrancing as Church’s masterpiece, the Pattinson image offers a jumping off point to tell the story of an important yet neglected period of American photographic history.

Like so many other world travelers of his era, Pattinson visited Niagara Falls to take in its natural beauty. With his daguerreotype camera, which had only just been invented a year earlier, Pattinson would have used his chemistry skills to develop the first series of images that showed views of the American and Horseshoe Falls.

The advent of photographic technology, first the daguerreotype, followed by processes like salted paper prints, albumen prints, cyanotypes, heliotypes, tintypes and platinum prints leading up to the Kodak in 1888, would make the great spectacles of the American West famous. But neglected in this version of American photographic history are the early images that capture the landscapes of the eastern United States.

That’s why Diane Waggoner, curator of 19th-century photographs at the museum, organized the ambitious “East of the Mississippi: Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Photography,” which opens this week and will run through mid-July.

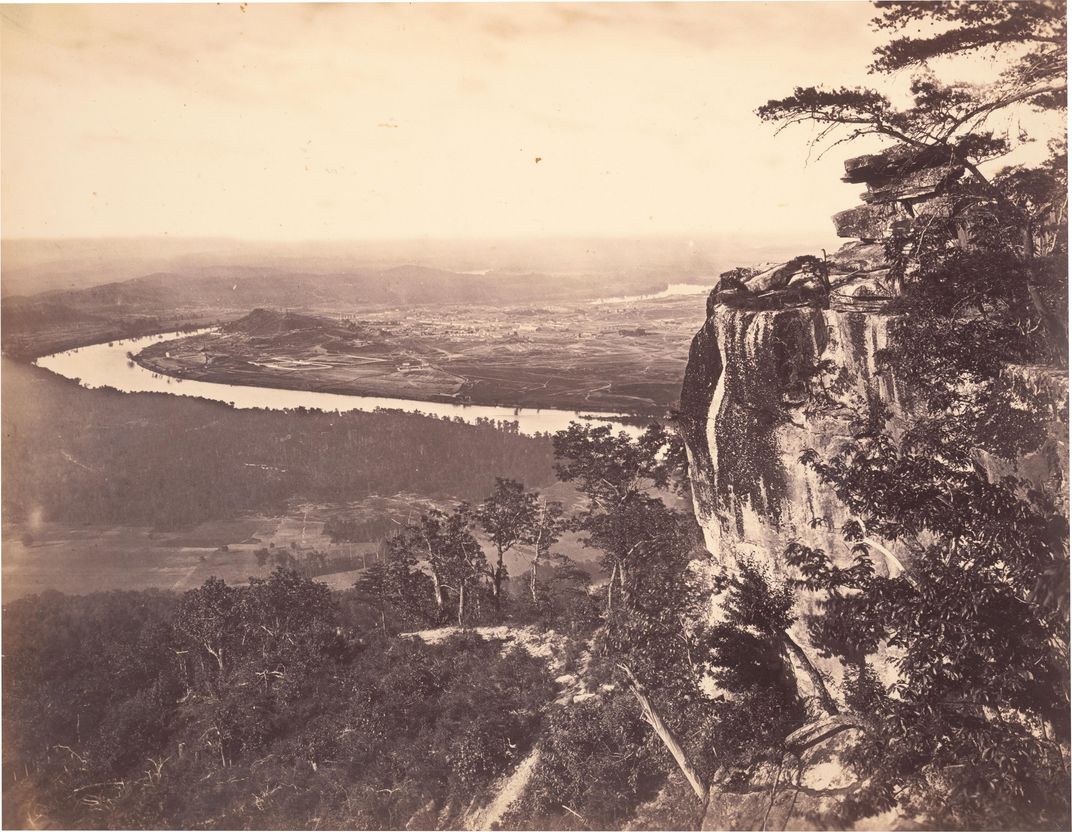

The first overarching survey on early eastern landscape photography, the exhibit focuses on the advancement of photography in a region that had already borne the brunt of invasive human activity. Unlike the West, which was only beginning to see the spread of industrialization, the American east was so heavily settled by the 1880s that, as Waggoner explains, eastern landscape photographers used the medium to advocate for conserving land that was already under threat from commercial and industrial forces.

Take Niagara. By the time Pattinson visited, a cottage tourism industry had already changed the landmark. While in his images, the natural beauty of Niagara comes into focus, other early daguerreotypes record the hotels that populated the area. Later in the century, photographers like George Barker would document how Niagara’s banks had become lined with mills and manufacturing buildings. Their work contributed to the “Free Niagara movement,” which ultimately led to the creation of the Niagara Reservation, New York’s first state park in 1885.

On the occasion of the opening of the exhibit, Waggoner spoke to Smithsonian.com about resurfacing this neglected chapter of American history.

When did you first become interested in telling this story?

I came across numerous photographers whose work may have regional reputations, but really had never received much of a national platform and had been [somewhat] marginalized within the history of photography. I really wanted to shine a spotlight on a number of these photographers who did fantastic work.

At the same time, I wanted to look at the particular concerns of these photographers. What were the themes that began to emerge? How did it change over time? What were the earliest known landscapes that existed in the United States? I'm thrilled that we were able to show a few of those earliest-known landscape daguerreotypes that were taken in either late 1839 or 1840, right at the beginning of the medium.

Who were these early photographers out east?

It was a real mix. A lot of them were scientists. Some of them I think of as classic 19th-century men interested in lots of kinds of scientific phenomena, like Henry Coit Perkins. But that's not most of them. Most were men who took up photography as a business; they saw it as an opportunity. It was a new technology where you could start a business and make money.

The catalogue for this exhibition notes that early American photography was modeled on British precedents. In what ways did that influence stretch across the Atlantic?

If you think about it, how was a photographer going to approach a landscape at that moment? What are the precedents? What are they used to seeing? They're going to want to make those images look like what they expect a landscape image to look like.

[T]he way landscape photography develops in America is also very different from the way it develops in Britain and France. So many of the earliest photographers came from a much more mechanical and scientific background. They were much more experimenters. Not that many of them had trained as artists. That [mostly] came a little bit later.

When do we start to see that aesthetic shift in early American landscape photography?

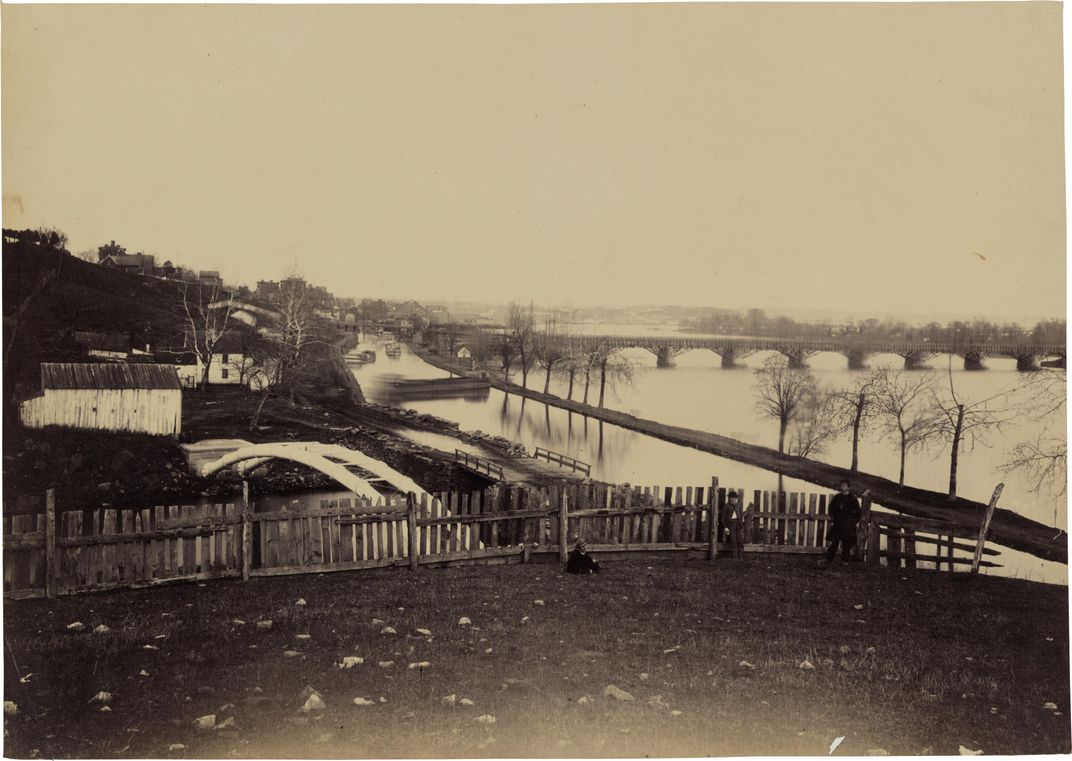

I think probably at the time of the Civil War you begin to see that more overtly. I’m thinking about Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War, and George Barnard's Photographic Views of [Union Army General William] Sherman's Campaigns. There are many reasons why those publications were made and other Civil War photography was made and marketed. Some of it was to celebrate the engineering accomplishments, but there's also [a] melancholy sense that Barnard in particular imbues the landscape [with] as he's going back and photographing these battlefield sites after the fact.

It may not have been made for necessarily overt reasons. Barnard wanted to sell his publications and make a living from it. But I think he couldn't help but be affected by his response to the war itself and his experience.

Later on in the century, there are photographers like Seneca Ray Stoddard and Henry Hamilton Bennett, who helped create tourism interest in places like the Adirondacks and the Wisconsin Dells. At the same time, they also became aware of the environmental effects both of industry and the development that catered to the tourism industry. Both of them, in different ways, advocated for the preservation of the scenery.

What were some of the ways that you can see photography telling this story of the changing 19th century landscape?

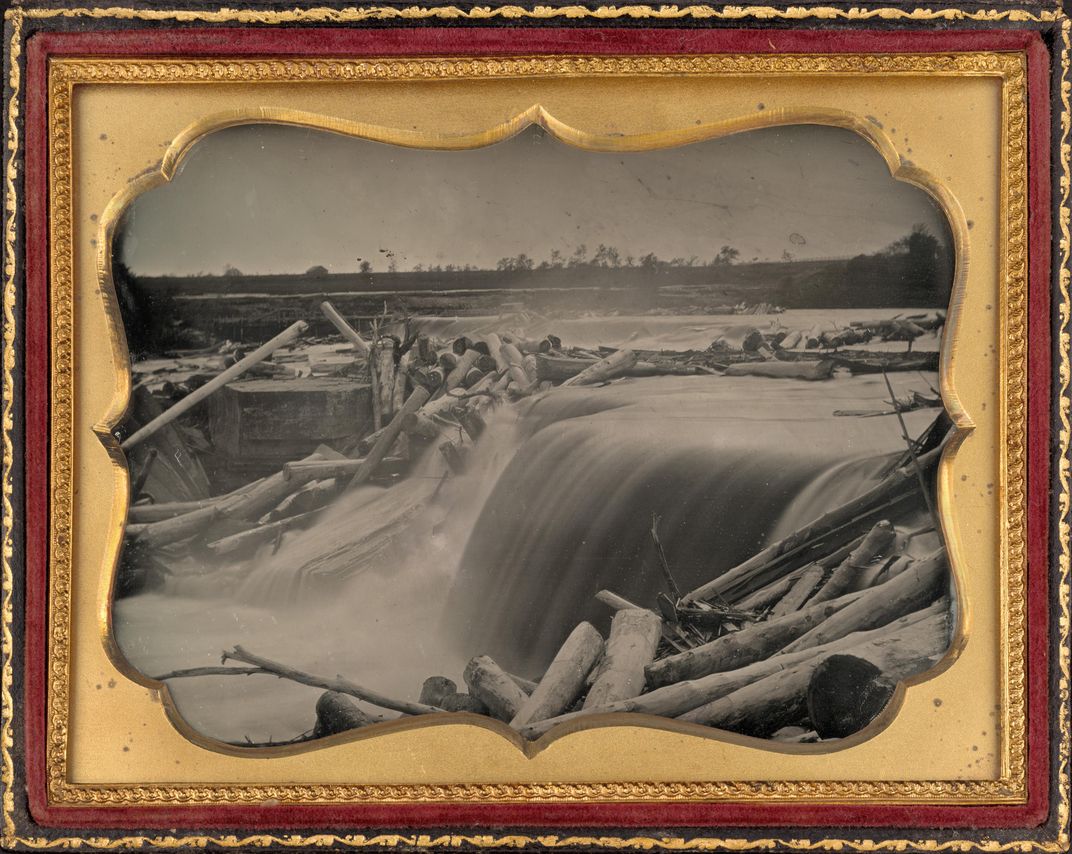

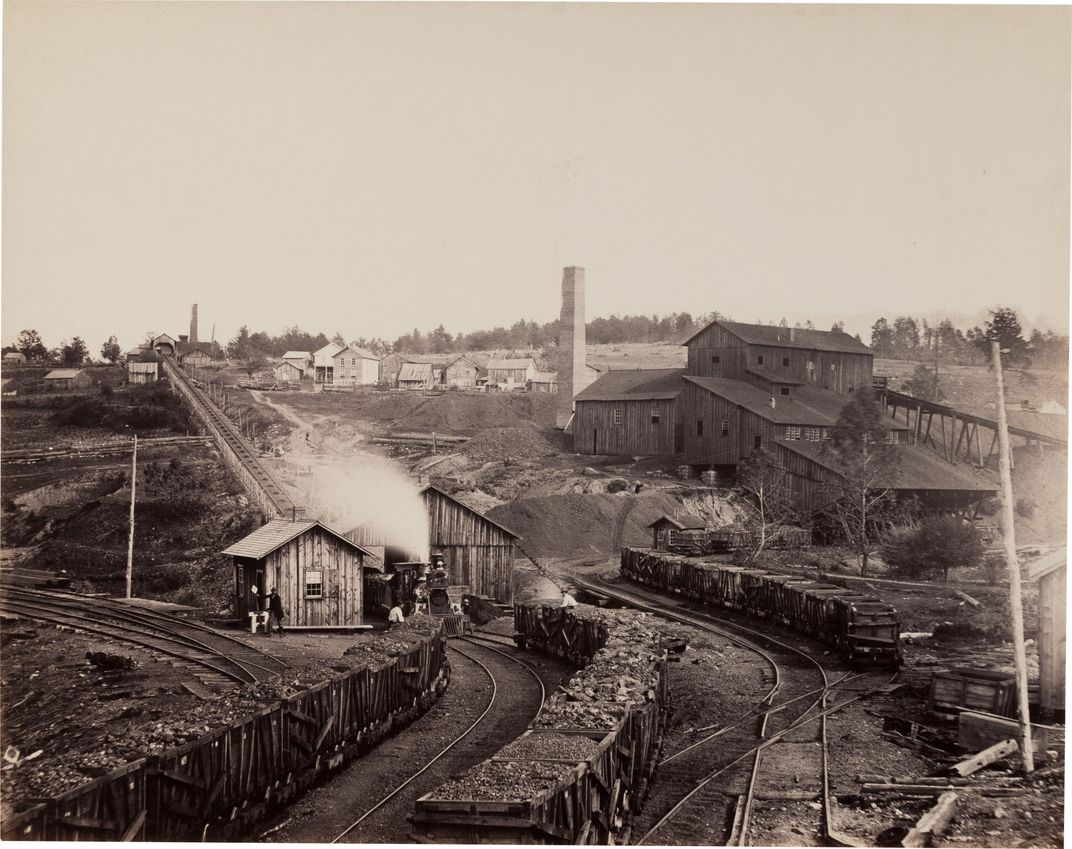

There’s a reckoning with this tension of photographing these places—which are beautiful, the pride of America, the wilderness, the amazing natural wonders to be found—at the same time that this constant alternation and change was happening to this very landscape, whether it was through the tourism industry, the building of railroads, or the beginning of extraction of natural resources.

There's the series of photographs of the coal areas of northeastern Pennsylvania, and the oil regions in Pennsylvania as well—that nature versus culture. It goes back to Thomas Cole's essay on American scenery in the 1830s, from just before photography, where he talks about America as [a] place full of amazing natural wonders, but at the same time ripe for development and expansion.

I was kind of amazed realizing through this project how much had already happened to dramatically change the landscape. That's a different trajectory that happens in the eastern landscape versus the West because the West is in the process of being settled. It happens a little bit earlier in the East, the built environment with the railroads, this huge web of railroads throughout the eastern United States.

The tug between development and preservation of land is a common theme today, but seeing that tension start to play out in these photographs of the east really surprised me.

The minute you start doing things where you are affecting the landscape, there's going to always be this corresponding attitude of “wait a minute.” Certainly the 19th century itself is the moment people start thinking about historic preservation in general.

The photographers in this exhibition might be known regionally, but they aren’t exactly household names. Can you tell me about a few who stood out to you?

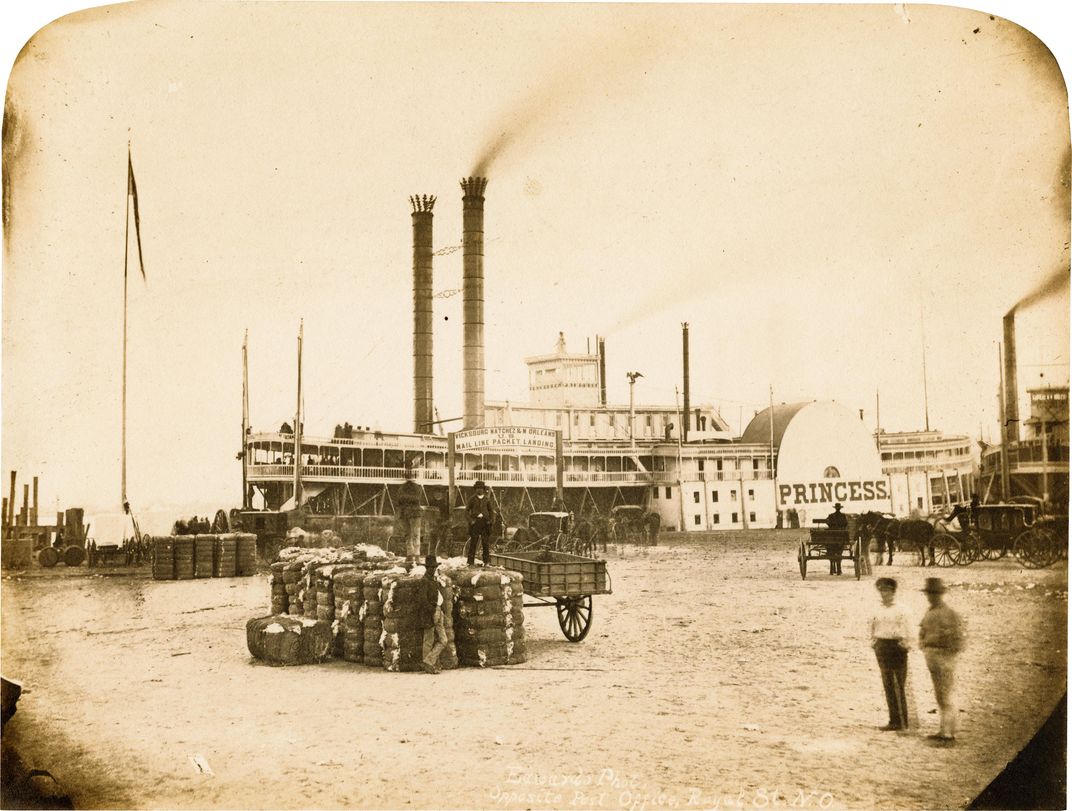

Thomas Easterly, a Saint Louis daguerreotypist who was the master of the daguerreotype. He was by far the most accomplished—the daguerreotype genius of America, basically. He operated a portrait studio, but on his own initiative, he photographed all the kinds of changes in St. Louis over the course of a couple of decades. He's the only photographer that sticks to the daguerreotype into the 1860s, well after most had abandoned it for paper process...He's really one of the showstoppers.

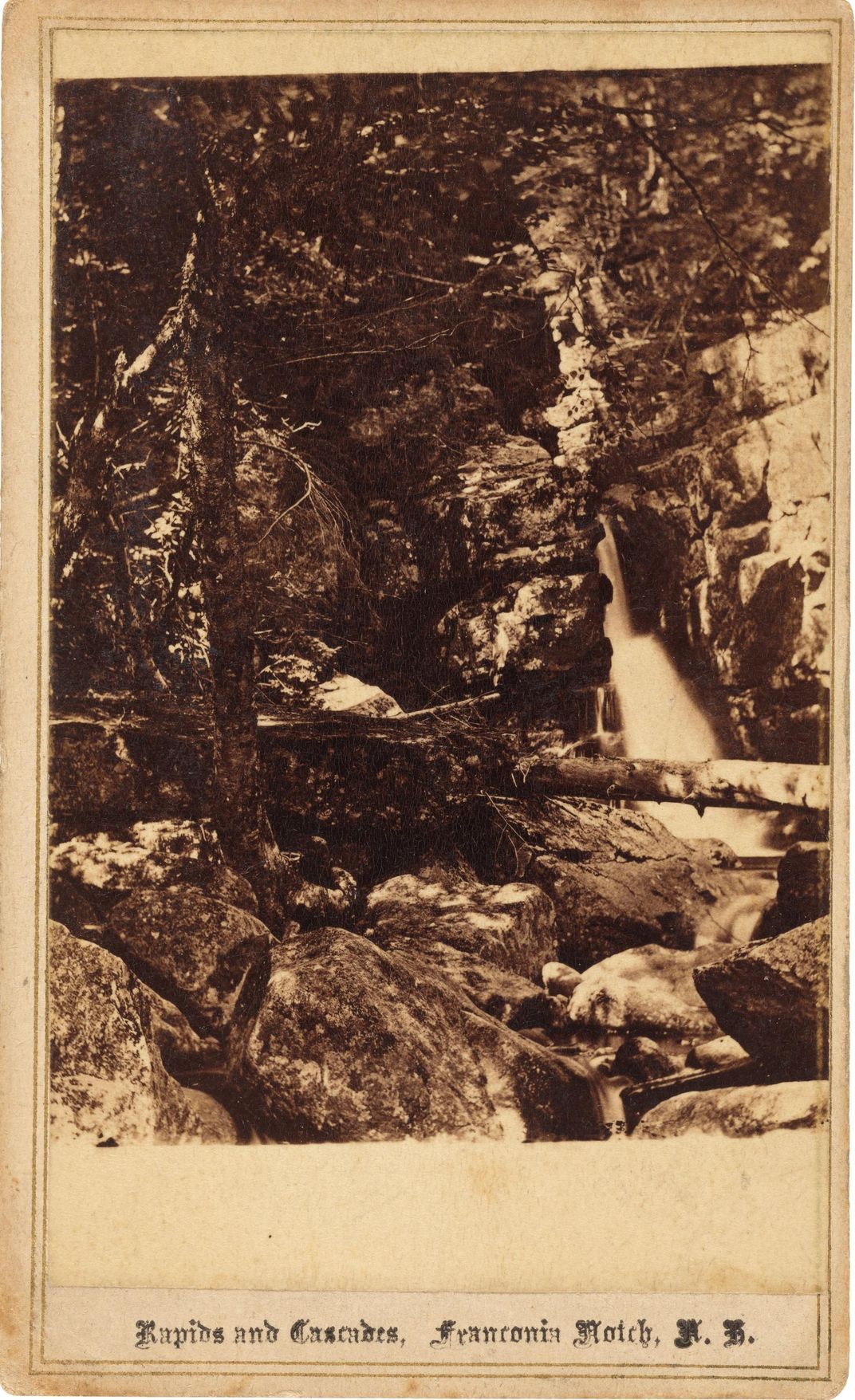

James Wallace Black—his really early work in [his native New Hampshire’s] White Mountains in 1854 is quite incredible.

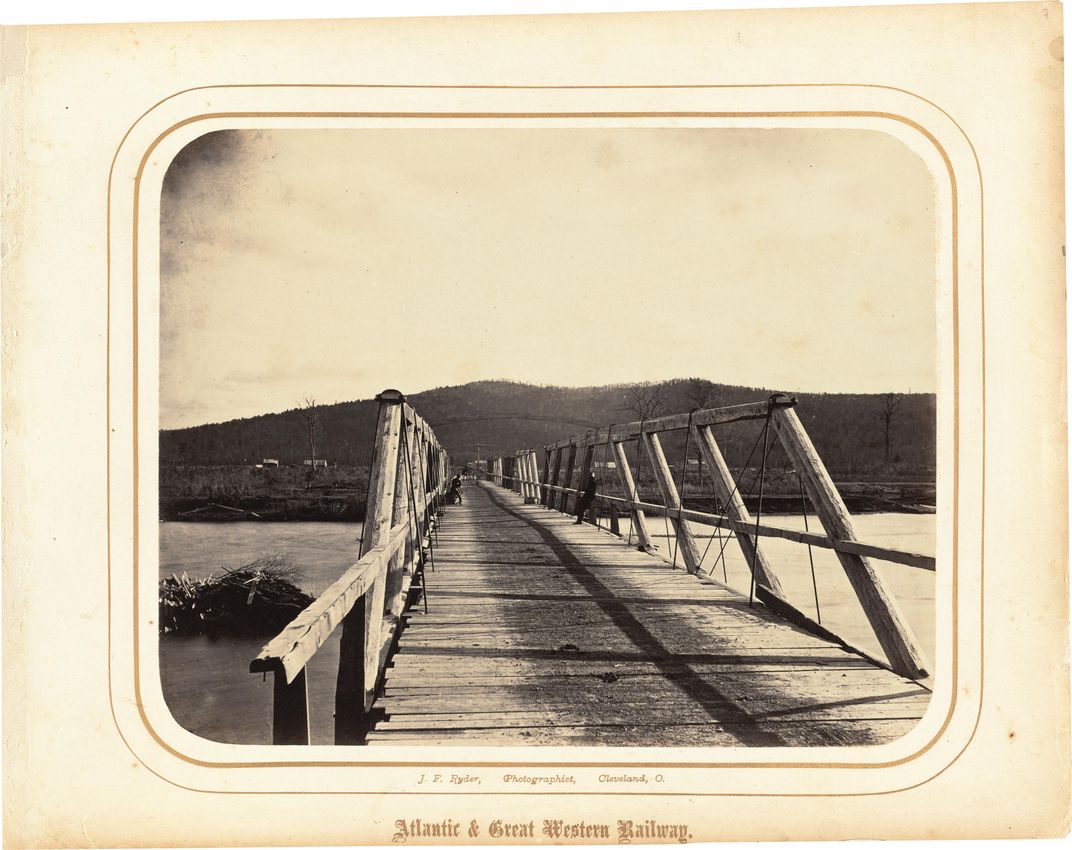

James F. Ryder was the first photographer in America hired specifically by a railroad company, and George Warren pretty much helped invent the college yearbook. He made these amazingly beautiful photographs of architecture and landscape around college campuses that was catering to the graduating seniors who then purchased both the portraits and these views of the campus and architecture and bound them into albums

Henry Peter Bosse [made an] incredible series of cyanotype prints along the upper Mississippi River as part of [his] work [for] the Army Corps of Engineers. He was photographing the upper Mississippi as it was being tamed and altered to make it easier for navigation, but he clearly approached the landscape from not just a technical perspective but [also] an aesthetic one as well. And then William H. Rau, who was photographing for Pennsylvania Railroad and the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1890s. He produced these really stunning mammoth-plate prints.

Would these photographers have had exhibitions during their lifetimes?

[In some cases] these were commissions for the companies. They may have ended up in historical societies or museums, but you [can] trace it back to the companies who commissioned them. That's true for someone like [William] Rau or James F. Ryder. He was a very active, very prominent photographer throughout the 19th century, but didn't do anything with the work until he wrote his autobiography toward the end of his life.