Sun-scorched and wind-scoured, the place that geographers refer to as the Sahara-Sahel stretches across Africa between the desert and the great savanna. Though dozens of tribes and ethnic groups live in the region, which is about the size of the contiguous United States, the estimated population of 135 million is divided among all or part of several nations—Senegal, Algeria, Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Libya. One common thread, aside from the extreme environment, is religion, with the great majority of people practicing Islam. The cultural glories are countless—the petroglyphs of Niger, the music of Chad, the libraries of Timbuktu—but what we in the developed world tend to hear about these days are the problems. It is hot and getting hotter, according to climate scientists, poor and getting poorer, say the economists. Food and water are becoming scarcer while the number of people is rising rapidly. Investment is lagging, services evaporating. Lawlessness, armed conflict and terrorism are on the march.

Those are generalities, to be sure, but recent official reports from sources as diverse as the U.N., the CIA and academics agree that the people of the Sahara-Sahel face a deepening crisis. This past November, the OASIS Initiative, an international humanitarian group based at Berkeley, California, urged governments and aid groups to help by increasing agriculture, strengthening security and empowering young women, which would curb population growth, among other benefits. The group’s report appears in the scientific journal Nature, but along with the charts and other data treatments are decidedly alarming terms—“powder keg,” “grim,” “living on the edge,” “catastrophe”—intended to pierce the immobilizing complexity of aiding distant societies on the brink.

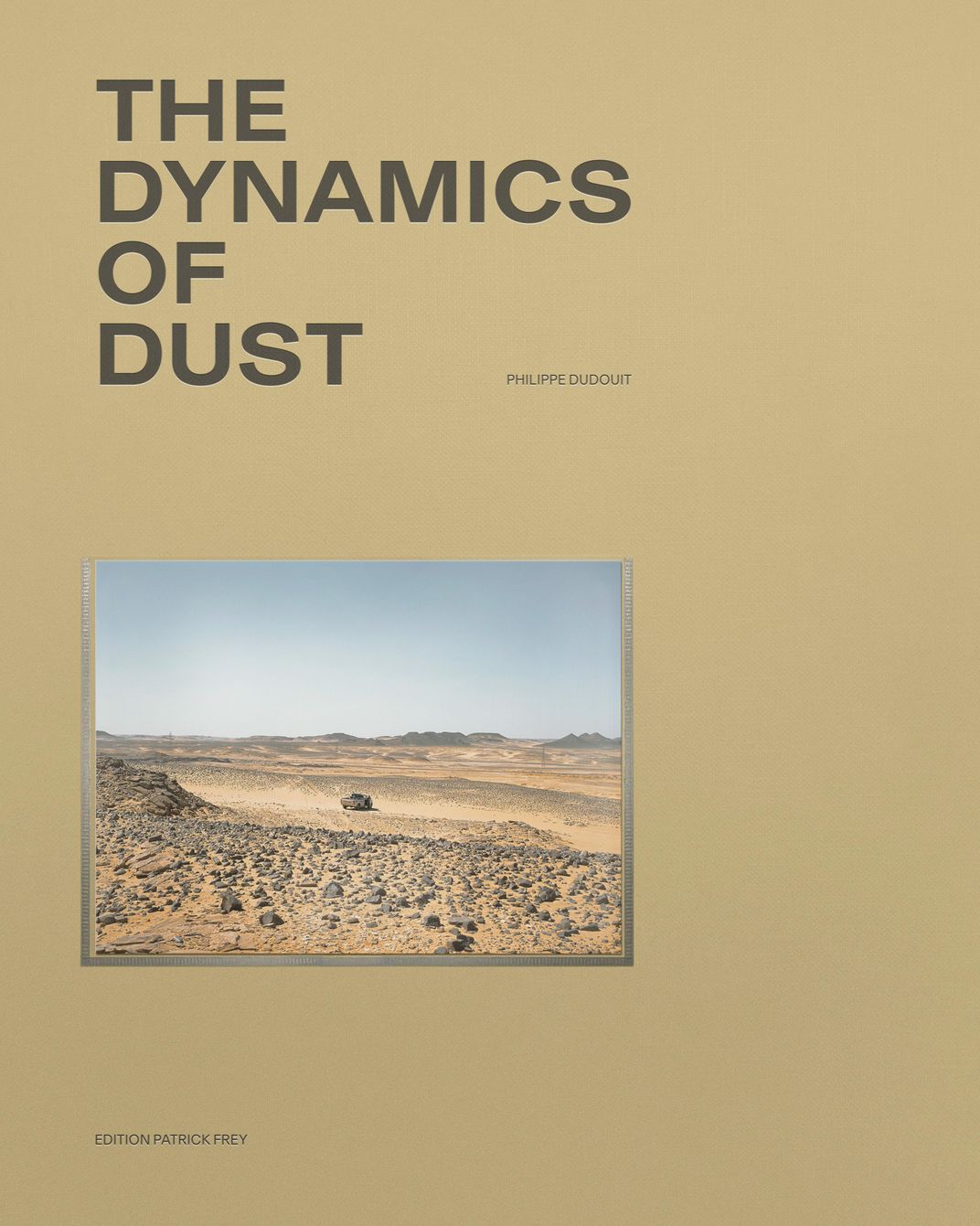

The emergency is not lost on Philippe Dudouit, a 42-year-old Swiss photojournalist who has lived among diverse groups of people in the rural Sahara-Sahel off and on since 2008. Indeed, he has closely observed the decline himself. To look at the photographs he has created over the past tumultuous decade, many of which are published in the United States this January in his book The Dynamics of Dust, is to get a whole new sense of the word “arresting.” These pictures stop you. Sunburned eyes gaze over a scarf worn as a disguise or to keep out the windblown sand, or both. An empty guard tower’s view of endless desert. Long-abandoned oil-drilling equipment. In such stark images you feel the unforgiving nature of the place and the toughness of the people. They are traders, rebels, smugglers and merchants, and without a single explanatory word or statistic you feel they are in a very, very hard situation. And isn’t that the point of documentary art, to let you feel another human being’s predicament?

The Dynamics of Dust

Since 2008, Swiss photographer Philippe Dudouit has documented the new relationships that historically nomadic inhabitants of the Sahelo-Saharan region have forged with a territory through which they can no longer pass freely or safely.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/73/c373056c-55c1-4527-9f1a-4ae15a221d09/bluenigermountains_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/fd/a1fd2347-ce3b-43cc-8c21-67f08137b2cc/bluenigermountains_lfo.jpg)