Photos for All Time

A new book, At First Sight, draws on all the Smithsonian’s vast archives to chart photograph’s profound place in history

From the beginning, photography traded in volume. Picture upon picture, photographs began to form an inventory of our world—a visual catalog of things and people that were important: the tallest building, the fastest horse, our likenesses in youth and old age. We visited far-off places and experienced other cultures that we would never see in person. The surface of the moon was photographed through telescopes, bacteria through microscopes. "As the bee gathers her sweets for winter," promised inventor, painter and budding photographer Samuel F.B. Morse at the announcement of photography's birth in 1839, "we shall have rich material...an exhaustless store for the imagination to feed on."

If only Morse could have known just how rich and exhaustless! The Smithsonian Institution alone holds more than 13 million photographs (the exact number awaits cataloging), housed in nearly 700 special collections and archive centers within 16 museums and the National Zoological Park. Some are negatives; others, original prints. They represent nearly 160 years of collecting, as well as a varied range of impulses and photographic intentions.

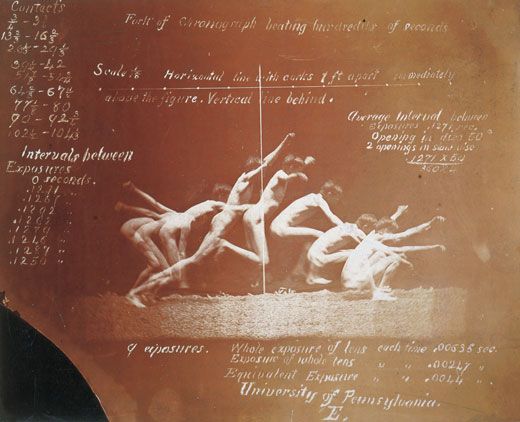

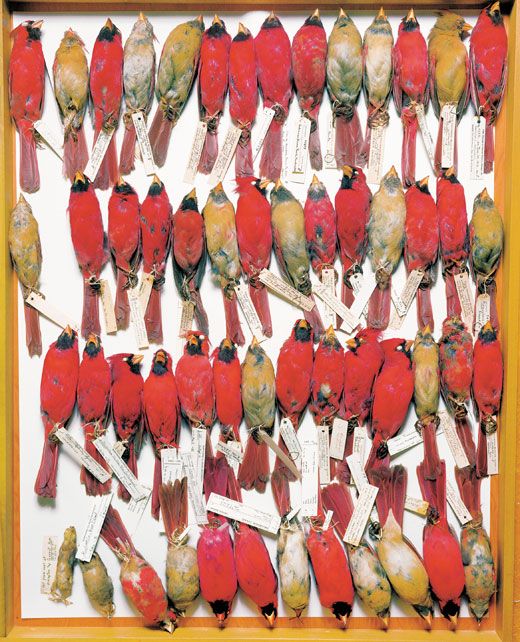

Many of the collections are catalogs of specimens: fish skeletons, fossilized plants, airplane models. Others reflect the Smithsonian's interest in exploration and scientific research—photographs from geological surveys, records of early attempts at human flight, views of anthropological sites and distant planets, motion studies of humans and animals. Still others, acquired more recently, represent photography as a technology or an art form. Besides providing a unique chronicle of what at the time seemed important to document and preserve, these collections validate the role photography has played in the formation of a sense of ourselves as individuals, as a people and as a nation.

In 2000, after more than 20 years as curator of photography at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and finding fascinating photographs in all sorts of unexpected places within the Smithsonian—often by serendipity—I took on an assignment to organize a book of photographs drawn from collections throughout the entire Institution. The images on these pages are from that book, At First Sight: Photography and the Smithsonian, which was published in December 2003 by Smithsonian Books. From the first photographs ever made in Europe and America to digital images beamed back from Mars, these pictures tell us where we've been, who we are and what we can achieve.

Both photography's invention and the creation of the Smithsonian Institution occurred in the mid-19th century, amid the worldwide quest for new kinds of knowledge that characterized the Industrial Age. As much as photography was born into a changing world, it also functioned as an agent of that change. Like today's digital technology, it launched innovations in nearly every imaginable aspect of modern life, from the way we tried criminals to the way maps were made. It changed how people viewed themselves and others. Time was frozen and history became more tangible.

The Smithsonian's interest in photography was immediate. After a fire in 1865 destroyed not only the Institution's first building but also its first exhibition (of paintings of Native Americans), a new exhibit of Indian portraits was quickly assembled, using photographs. The Smithsonian hired its first photographer, Thomas William Smillie, in 1868. Smillie, it turns out, was not only a great picture taker but also an indefatigable collector. His first purchase for the National Museum was Samuel Morse's camera equipment. In 1913, preparing for a major exhibition of photographs at the Smithsonian, he arranged for Alfred Stieglitz, the renowned promoter of photography as an art, to put together a collection of pictorialist photographs that the Institution then purchased (after a tough negotiation) for $200.

Smillie's own photographs are as remarkable as they are little known. His output was prodigious; he delighted in photography's technology as well as in the making of a well-rendered picture. He documented museum installations and specimens—from bird skeletons to Assyrian clay tablets—recorded the construction of Smithsonian buildings, and served as a photographer on scientific expeditions. Each box that I came across of his work contained histories of thought as well as objects of rare and surprising beauty. Because he demonstrated such a broad spectrum of purposes and intentions, I like to think Smillie guided my own expedition through the archives.

Ultimately, photography serves a patchwork of functions. It is an art form, a record-keeping mechanism, a means of communication and a medium whose usefulness is shared by the many disciplines of both the sciences and the humanities. Photographs have the power to teach as well as to excite the imagination, transporting us across time and space to new horizons.