Portraits of Baseball’s Tinker, Evers and Chance

The famed Chicago Cubs infielders were immortalized in verse—as well as through Paul Thompson’s lens

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Frank-Chance-631.jpg)

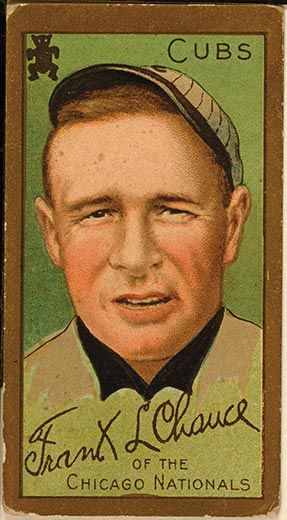

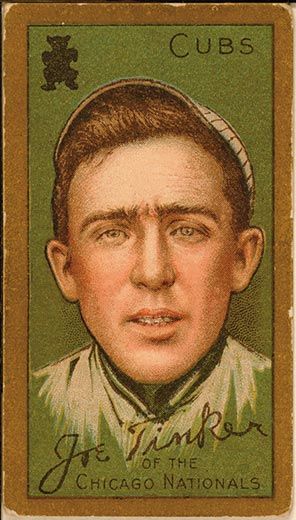

Forget bubble gum; the first collectible baseball cards came with cigarettes. The cards transformed the game, making household names of its greatest players. In the first decade of the 20th century, baseball's biggest draws included three Chicago Cub infielders who would become linked in legend: Tinker, Evers and Chance. That melodic triplet echoes down the corridors of the Hall of Fame, a box-score cadence whispering to those straining for the sounds of summers past. We can't get back to Chicago's West Side Grounds in October 1908 to see these three help the Cubs defeat the Detroit Tigers on their way to winning the World Series, but we can glimpse their era and their singular faces in baseball cards of the period, when the sport and American commerce intersected.

American tobacco companies began issuing celebrity cards with cigarette packs to boost sales in the 1880s. The first wave included black-and-white studio photographs of awkwardly posed ballplayers reaching for or swinging at a baseball hanging from an often visible string. Other cards, called chromolithographs, were printed in color. They usually bore legends identifying the players, their positions and their teams.

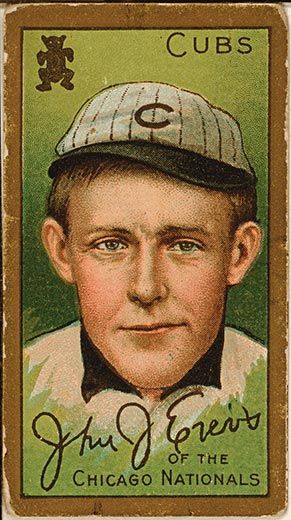

After 1900, as color printing techniques improved, cards became more realistic. About 1909, the American Tobacco Company, a holding consortium for the Big Tobacco lobby, issued a now-coveted series of cards bearing white borders. (A card from this series featuring Honus Wagner, the great Pittsburgh Pirates shortstop, routinely fetches seven figures.) In 1911, American Tobacco followed that series with one bordered in gold leaf. Called "gold borders," these were among the first to include the players' batting and pitching statistics on the cards' other side.

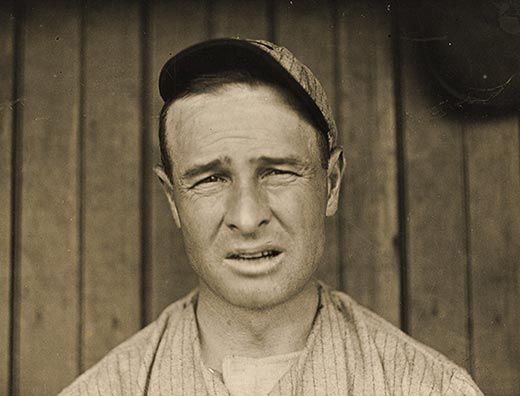

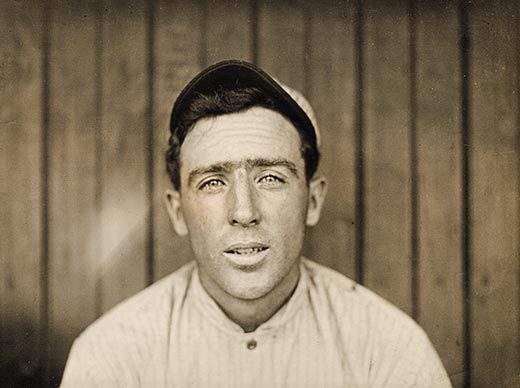

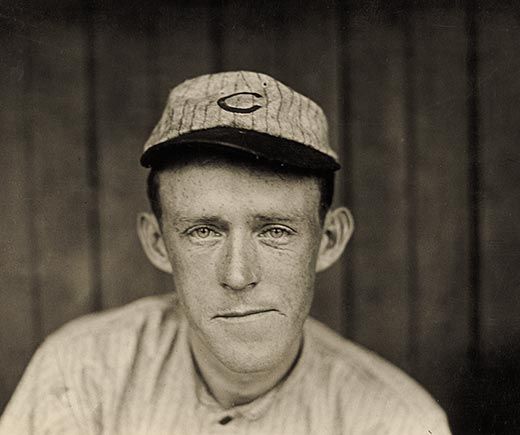

The gold borders sported another enhancement—portraits based on a remarkable series of contemplative close-ups by a New York City-based freelance photographer named Paul Thompson. Thompson, who built his reputation and his studio on a sitting with Mark Twain, would hire others to take pictures for him, but the gold-border portraits are attributed to him because they alone are copyrighted under his name.

Thompson produced the photographs before the 1911 season, taking head shots of the players against rough wooden backdrops at New York's ballparks. With a shallow depth of field and an unsentimental lens, he brought out in sharp relief the players' leathery faces and steel-eyed stares, capturing their pride, their toughness and the effects of extended exposure in the field. The rough dignity of his portraits survived the translation into color prints on cardboard.

Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers and Frank Chance were already stars when Thompson caught up with them. Tinker, a paperhanger's son from Muscotah, Kansas, had joined the Cubs in 1902, the same year as Evers, who had worked in a collar factory in Troy, New York, while playing for a minor-league team. Chance, the son of a banker in Fresno, California, first appeared on the club's roster in 1898, as a catcher. But as the team was rebuilt in 1902, manager Frank Selee put Tinker at shortstop, with Evers at second and Chance at first. Chance replaced Selee as player-manager in mid-1905. He would become known as "the Peerless Leader."

The trio anchored one of the best infields in the game during a decade of Cubs dominance (four National League pennants and two World Series championships). But they didn't always get along; Tinker and Evers came to blows before a game in September 1905 and stopped speaking to each other for years—even as they continued to demand the best baseball from one another. Although they never led the league in double plays, Franklin Pierce Adams of the New York Evening Mail gave that impression in the opening lines of his oft-quoted doggerel:

These are the saddest of possible words:

"Tinker to Evers to Chance."

Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

The gold-border cards based on Thompson's portraits appeared in 1911—just as the Cubs had begun to falter. By 1913, Tinker had been traded to Cincinnati, Evers had replaced Chance as the Cubs' manager and Chance had left to manage the Yankees. The former first baseman died 11 years later of heart failure stemming from influenza and bronchial asthma; he was 47. Evers died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1947, at age 65; Tinker expired the next year, on his 68th birthday, of respiratory difficulties.

The trio were inducted into baseball's Hall of Fame in 1946, a selection that is still debated. Bill James, the baseball historian and statistician, has argued both sides of the issue. He once contended that the players' individual statistics were not Hall-worthy; later, he concluded that the whole of their accomplishments mattered more, writing, "It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that [the 1904-13 Cubs] won more games with infield defense than any other team in the history of baseball."

Photographer Thompson left behind a more slender record: even such basic biographical information as the dates of his birth and death is hard to establish. But some two dozen of his player portraits survive in the Library of Congress, bringing to life the subjects' determination, their enduring passion for a physical game and the ravages of a lifestyle that predated the luxury travel, sophisticated equipment and personal trainers of today. The gold-border cards that followed created heroes of banker's and paperhanger's sons alike, filling ballparks and selling cigarettes. The bubble gum came later.

Harry Katz is the principal author of Baseball Americana: Treasures from the Library of Congress. He was head curator of the library's Prints and Photographs Division from 2000 to 2004.