Portraits of Resistance

The inaugural show of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

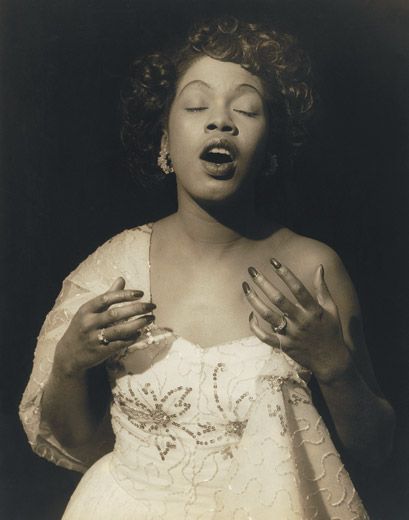

Sarah Vaughan looks enraptured—eyes closed, lips parted, hands held at her chest in an almost prayerful gesture. This photograph of the late "Divine One," nicknamed for her otherworldly voice, introduces visitors to an exhibition of 100 black-and-white photographs of African-American activists, artists, scientists, authors, musicians and athletes at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. (through March 2). A scaled-down version of the exhibition, co-sponsored by the International Center for Photography in New York City, will travel to several cities starting in June.

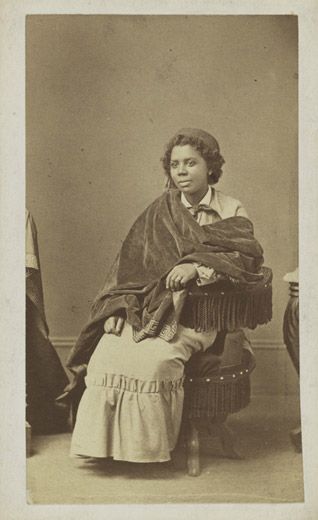

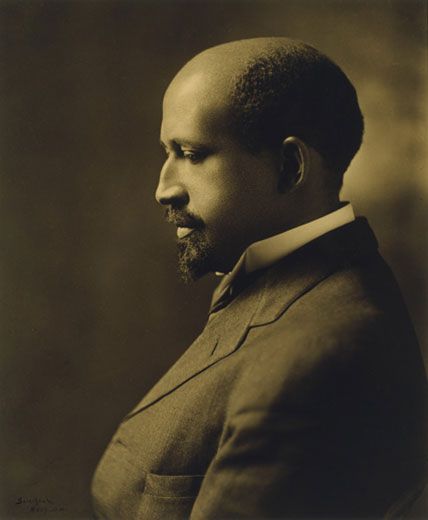

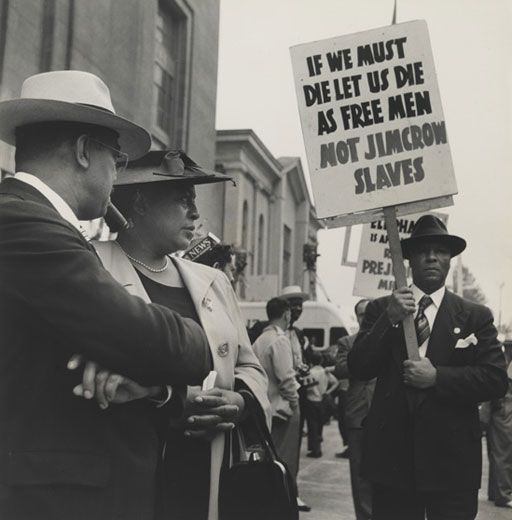

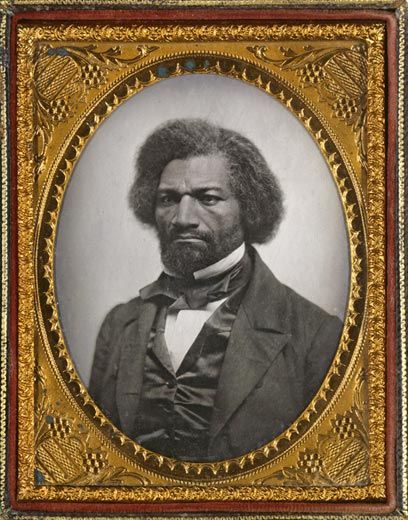

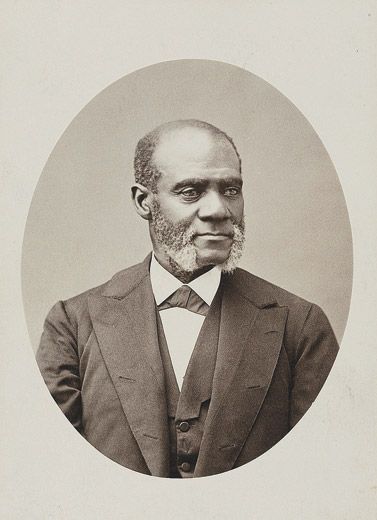

Drawn from the gallery's collections, the photographs span the years from 1856 to 2004 and make up the inaugural exhibition of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, which was established by Congress in 2003 but won't have a home of its own before 2015. The exhibition title, "Let Your Motto Be Resistance," is from an 1843 speech to the National Convention of Colored Citizens in Buffalo, New York, by Henry Highland Garnet, a noted clergyman, activist and former slave. "Strike for your lives and liberties," Garnet urged his listeners. "Rather die freemen than live to be slaves. . . . Let your motto be resistance! Resistance! RESISTANCE!"

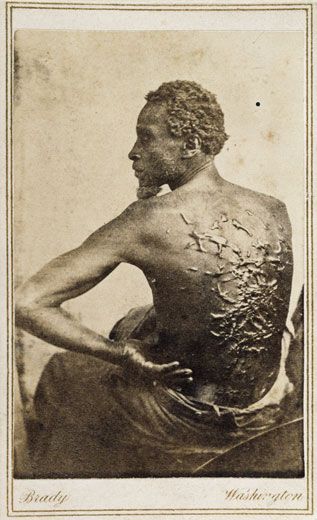

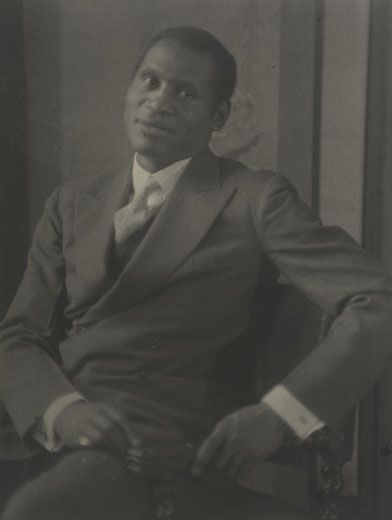

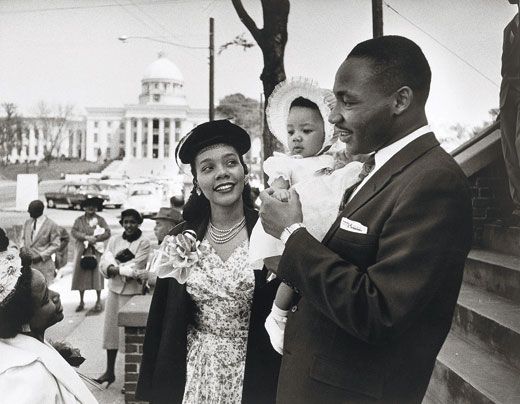

Viewing the portraits, which were selected by photography scholar Deborah Willis of New York University and curators Ann Shumard and Frank H. Goodyear III, a visitor is made aware of the many forms resistance can take. Some of the subjects were former slaves (Garnet, Sojourner Truth and a man known only as Gordon, whose shirtless back bears the shocking scars of many lashings). Some overcame endemic racism (bluesman "Mississippi" John Hurt and sculptor William Edmondson). Others sacrificed their very lives: Octavius Catto was murdered in 1871 at age 32 in Philadelphia's first election in which black citizens were allowed to vote; in a photograph likely taken that year, he appears strikingly handsome and full of promise. Martin Luther King Jr. is represented twice. In a sunny 1956 picture with his wife, Coretta, he holds baby Yolanda in Montgomery around the time he was leading a boycott to end segregation on Alabama buses. At his funeral in 1968, his daughter Bernice looks into his open coffin with apparent horror.

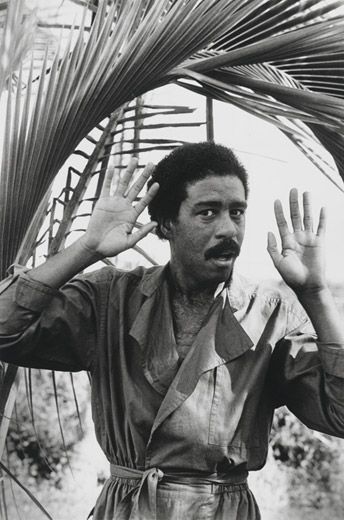

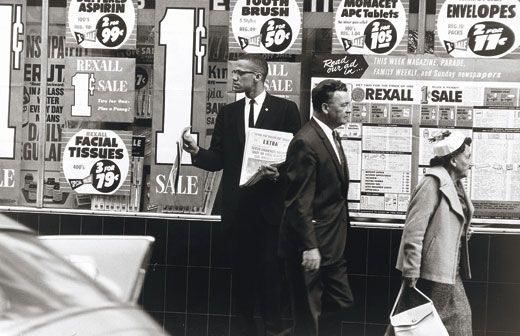

Numerous themes connect the lives of two other men whose activism shaped the 1960s. In one photograph, Malcolm X is selling newspapers on a New York City street for the Nation of Islam in 1962, two years before he severed ties with the black-separatist religious organization and three years before he was assassinated. "This image tells us that because of his commitment to the cause, Malcolm had the ability to be of the community, or of the organization, but still apart from it," says Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Muhammad Ali is framed almost heroically in a photograph from 1966, a year before the World Boxing Association stripped him of his heavyweight title and he was convicted for refusing induction into the Army on religious grounds during the Vietnam War. "The sense of courage and isolation that is the life of Ali is captured in this picture," says Bunch. "It speaks volumes about his ability to take a path other people wouldn't take." Indeed, Ali's determined stance during four years of legal battles at the height of his athletic career—the Supreme Court overturned his conviction and he later regained his title—would largely enhance his status as an international hero. Both the Malcolm X and Ali photographs were taken by Gordon Parks, who died in 2006, and who is himself the subject of a portrait. Parks, standing with a camera in 1945 at age 33, would mark the coming decades as a photographer, movie director, novelist and musician.

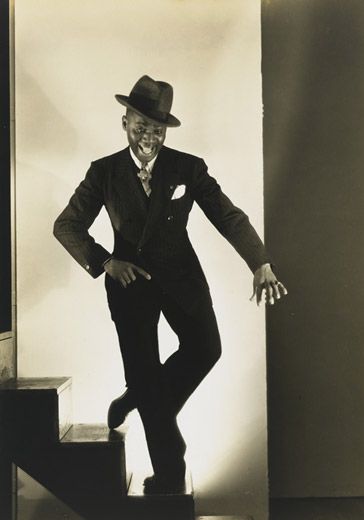

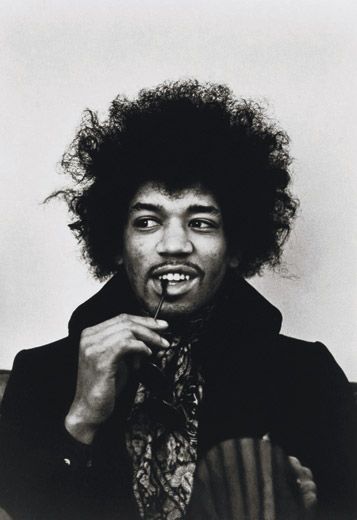

Most of the artists in the exhibition found creative ways to express adversity, celebrate their culture and expand their respective genres. A 1944 picture of tenor saxophonist Lester Young soloing with the Count Basie band is a discovery. Linda McCartney's playful 1967 portrait of guitarist Jimi Hendrix is, well, electric. In 1978, Helen Marcus captured a pensive Toni Morrison, whose novels ingeniously intertwine the wealth of black culture and the heart-rending power of black history.

"When I looked at these images, I saw almost the whole history of race in America," Bunch says. "I saw the pain of slavery and the struggle for civil rights, but I also saw the optimism and resiliency that has led to an America that is better than America was when we were born. It is very powerful to remember." Ultimately, the story these photographs tell is of the will of African-Americans who allowed no legal, physical or psychological depredations to suppress the joy and artistry inside them—and who changed the world in the process.

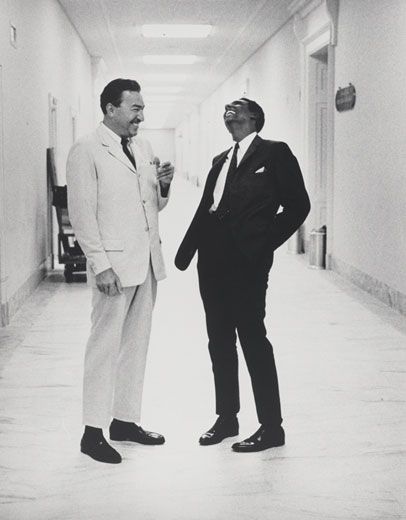

Perhaps the most engaging moment is provided by New York Times photographer George Tames. In his photograph of New York City's first black congressman, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and the young black-power advocate Stokely Carmichael, the two are laughing in the corridors of a Congressional office building circa 1966. The colorful, controversial Powell had spent decades working to end segregation and to pass civil rights legislation, while Carmichael was known for the fiery speeches he delivered principally on the streets. The image can be read to suggest that no matter how divergent the strategies of African-Americans engaged in the fight for equality, most were united by a dream more powerful than their differences.

Lucinda Moore is an associate editor of Smithsonian.