Presenting China’s Last Empress Dowager

The early 20th-century photograph of Empress Dowager Cixi captures political spin, Qing dynasty-style

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Object-Empress-Cixi-631.jpg)

Spin doctoring—the art of turning bad news into good and scoundrels into saints—goes back a long way. How far back is subject to debate: To the bust of Nefertiti? Roman bread and circuses? Jacques-Louis David’s heroic paintings of Napoleon? An exhibition of photographs from the dawn of the 20th century, now at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, provides a look at spin, Qing dynasty-style.

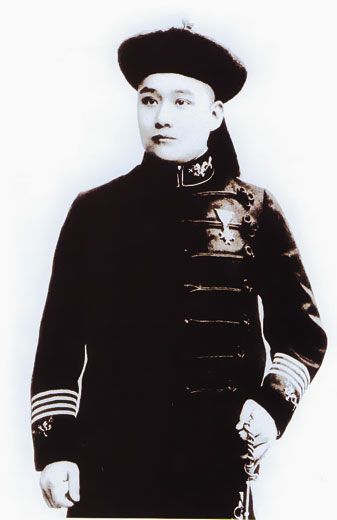

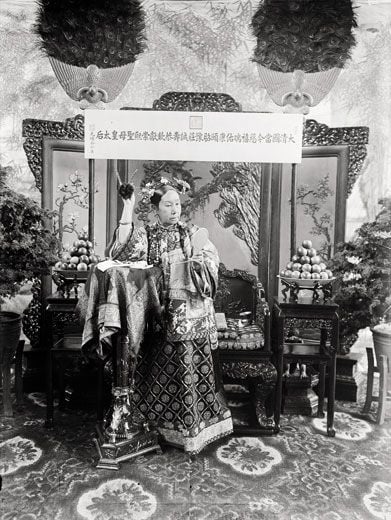

The photographs’ primary subject is Empress Dowager Cixi, the dominant figure in the Qing court for more than 45 years until her death in 1908, at age 72. The photographer was a diplomat’s son named Xunling. Though not a charmer, even by the somber photographic portrait standards of the day, the empress dowager seemed to like the camera and imagined that the camera liked her, says David Hogge, head of archives at the gallery and curator of the show. “She thought about self-representation, and—out of the norm for Chinese portraiture—she sometimes posed in staged vignettes that alluded to famous scenes in court theater. Sometimes she looked like a bored starlet.”

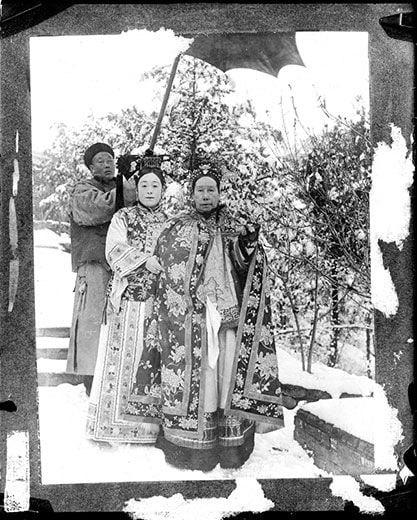

Vicki Goldberg, a New York-based historian of photography, points out that Xunling’s style was a bit behind the times, though “there was still plenty of traditional portrait work being done.” In the West, she says, group portraits were often made for family albums; a Xunling photograph of, say, Cixi and attendants at the top of some steps in a palace garden “may have been the photographer’s way of putting the empress dowager on a pedestal.”

By 1903, the year Cixi posed for Xunling, she needed a boost. True, she had been the de facto ruler of China since 1881, maneuvering her way out of concubinage by bearing Emperor Xianfeng a male heir and then engineering a palace coup. But the imperial court was isolated from both its subjects and the foreign powers then building spheres of influence in China, and eventually she made a miscalculation that brought her grief.

In 1900, Chinese insurgents known as the Righteous Fists of Harmony (and dubbed the Boxers by foreigners) rose against both the Qing dynasty and Western influences. Christian missionaries and Chinese Christians were slain, as were foreign diplomats and their families. To blunt the Boxers’ threat to the dynasty, Cixi sided with them against the Westerners. But troops sent by a coalition of eight nations, including England, Japan, France and the United States, put down the Boxer rebellion in a matter of months.

Cixi survived, but with a reputation for cruelty and treachery. She needed help dealing with the foreigners clamoring for greater access to her court. So her advisers called in Lady Yugeng, the half-American wife of a Chinese diplomat, and her daughters, Deling and Rongling, to familiarize Cixi with Western ways. With them came their son and brother, Xunling, who had learned photography in Japan and France. He began making a series of glass-plate negative portraits.

The empress dowager probably directed the photographer, not the other way around. Archivist Hogge says she may have taken the camera-friendly Queen Victoria as her role model. Sean Callahan, who teaches the history of photography at Syracuse University, agrees: “Xunling’s pictures bear little evidence of his having much feeling for Chinese art history traditions”but resemble those of the court of Queen Victoria, “to whom...Cixi bore a certain physical resemblance.”

Cixi used the portraits as gifts for visiting dignitaries—Theodore Roosevelt and his daughter Alice received copies. But soon, Hogge says, they showed up for sale on the street, which happened more commonly with photographs of prostitutes and actresses. How the portraits leaked is not known, but Hogge says, “it’s possible that the Yugeng family, having lived abroad, had a different idea of how images could be used.”

If their intent was to rehabilitate Cixi’s reputation, they failed. In the Western press, she was portrayed as something like the mother of all dragon ladies, and the impression remained long after she died in 1908, having appointed China’s last emperor, Puyi.

After Xunling’s sister Deling married an American who worked at the U.S. embassy in Beijing, she moved to the United States (where she was known as Princess Der Ling). When she died, in 1944, the Smithsonian Institution purchased 36 of Xunling’s glass-plate negatives, the largest collection of them outside the Palace Museum in Beijing, from a dealer for $500. Of the 19 prints on display, two are originals and 17 are high-resolution images made from scans of the negatives.

Xunling remained in China, suffering from ailments probably brought on by the photographic chemicals he used. He died in 1943, during World War II, when he may have been unable to get necessary medicine. He was in his early 60s.

“Xunling’s photographs are significant less because they are important historical documents of the last regent of China, but more because of what they say about the willful use of photography to shape history,” says Callahan. “The Dragon Lady may have been behind the curve when it came to political reform, but she was ahead of it when it came to using the medium to control her image.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)