Private Eye

Noted for her sensitive photojournalism in postwar magazines, Esther Bubley is back in vogue

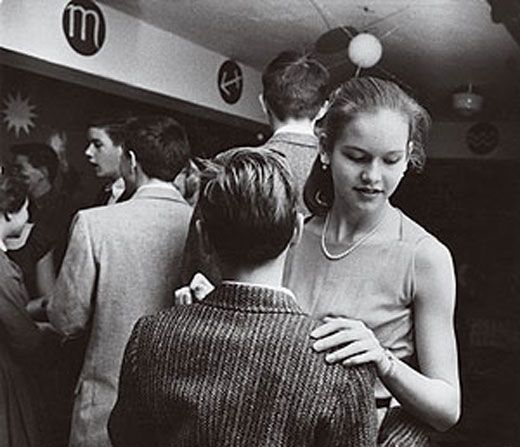

Esther Bubley was among the best-known photographers of her time, and for three decades blazed trails, especially for women, with her work for the government, corporations and magazines such as Life, Look and Ladies' Home Journal. Though she photographed celebrities—Albert Einstein, Marianne Moore, Charlie Parker—her talent was for ordinary life. "Put me down with people," she said, "and it's just overwhelming." Bubley's photographs of Americans in the 1940s and 1950s—sailors on liberty, bus riders, boardinghouse residents, hospital patients, teenagers at a birthday party—are so plain and yet so evocative they have long been included in museum exhibitions that try to convey something of the nation's character in those days. Her 1947 color photograph of a man in a fedora standing on a train platform in New York City, a painterly picture of long shadows and sooty red bricks, calls to mind the distracted loneliness of an Edward Hopper canvas. The movie scholar Paula Rabinowitz even theorizes that Bubley's photographs of women working in offices and factories in World War II contributed to a staple of the film noir genre—the strong-willed independent female freed from household drudgery by the war effort.

Since Bubley's death from cancer at age 77 in 1998, her reputation has only grown. The Library of Congress selected Bubley's work to inaugurate a website, launched last month, about female photojournalists. Jean Bubley, a computer systems consultant, runs a Web site highlighting her aunt's career. Major exhibitions of her work were held in Pittsburgh last year and in New York City in 2001, and a book of her journalism is scheduled for publication next year.

Born in Phillips, Wisconsin, in 1921 to Jewish immigrants—her father was from Russia, her mother from Lithuania—Bubley started making and selling photographs as a teenager. After college in Minnesota, she went to Washington, D.C. and New York City seeking work as a photographer, but found none. Still, she showed her pictures to Edward Steichen, future photography curator at the Museum of Modern Art, who encouraged her (and would later exhibit her work). In 1942, she landed in the nation's capital, shooting microfilm of rare books at the National Archives and, later, printing photographs at the Office of War Information, successor to the historical section of the Farm Security Administration, which had supported such celebrated documentary photographers as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and GordonParks. In her off hours, Bubley took pictures of single working women. Her break came in 1943, when the photography office's director, Roy Stryker, sent her on a six-week cross-country bus trip to capture a nation at war. Her late 1940s photographs of Texas oil towns for Standard Oil (New Jersey), a project also overseen by Stryker, are postwar landmarks.

Bubley was a successful freelancer and, in 1954, the first woman awarded top prize in Photography magazine's competition for international work, for a photograph of women in Morocco made for UNICEF. She produced a dozen photo essays between 1948 and 1960 on "How America Lives" for Ladies' Home Journal. As the magazine's editor, John G. Morris, put it in 1998, "Bubley had the ability to make people forget she was even around; her pictures achieved incredible intimacy."

A private woman, Bubley, whose marriage in 1948 to Ed Locke, an assistant to Stryker, lasted barely two years, spent her later decades in New York City, making pictures of her Dalmatians and of Central Park, among other things. She did not have fancy theories about her calling. At age 31, she made an entry in a journal that caught the essence of her approach—direct, unadorned, essentially American and deceptively simple: "I am quite humble & happy to be one of those people who work because they love their work & take pride in doing it as best they can."