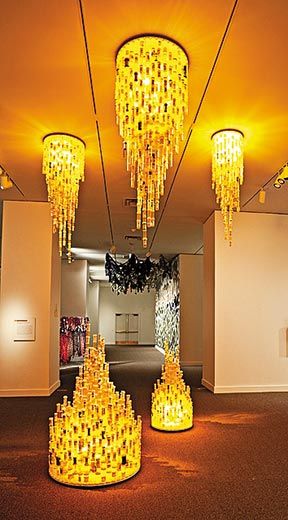

Q and A: Sculpture Artist Jean Shin

The artists creates sculptures from castaway objects such as old lottery tickets and broken umbrellas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jean-Shin-Common-Threads-388.jpg)

Jean Shin creates sculptures from castaway objects such as old lottery tickets and broken umbrellas. Megan Gambino spoke to her about her new show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, "Jean Shin: Common Threads."

How did this idea begin?

I'm always attracted to objects that have the potential to be reimagined differently from their current use or value in our society. I collected cuffs from my own pants, which I have to typically roll up about two and a half inches or cut off. In a way, the accumulation of cuffs over the years mapped my own body.

How do you collect enough?

I always start from my base, which is my friends and family. They are accustomed to getting these odd requests. But over the course of months, sometimes years, in which a project lives, I really do need to tap into a larger pool of people. If it's prescription pill bottles, it's nursing homes. It's brokering with the person who is embedded into that community, who is interested in my work and who realizes that it could fulfill an important purpose for me in the art making process.

Someone's trash is another's treasure?

Yeah, it's funny. That statement makes it seem like it's literally trash. But these castaway objects are sometimes things that people hold onto throughout their lives and have a hard time parting with, like trophies.

You collected 2,000 trophies in and around Washington, D.C.

The project [Everyday Monuments] grew out of my interest in Washington as a city planned around monuments. I wanted to choose a symbolic, everyday object that was a modest version of public monuments.

Your installations are sometimes described as group portraits.

I see every object as a part of that person's identity and personal history. Someone asked me why I didn't just buy 2,000 trophies, and that would have been a lot easier. But it really wouldn't have embodied people's lives.

For Everyday Monuments, you altered the trophies so that the figures were everyday people at work—stay-at-home moms, restaurant workers, janitors and mailmen. Manipulating the objects is part of your work. Why?

For me, it's a chance to get to know my materials because unlike a painter who knows his paint, his brushes and his canvas, I don't have that opportunity every single time I shift material. When you deconstruct something, you understand it, and you're able to put it back together and make wise decisions in the construction of the work. I feel compelled to have them be noticed differently, so I think it's important for me to take it apart and slightly tweak it. I've gone too far if I've made it into something totally unrecognizable. I want it to be something on that line between familiar and new.

You use hundreds if not thousands of the same type of found object in any one piece. What affect does the repetition have?

I love the contrast that it can simultaneously be about the minute and intimate and individual while at the same time looked at as the universal, the collective, the variations, the macro and the micro being seen at once.

What commentary are you making about consumerism, or excess?

Maybe just that it exists. My work wouldn't exist if I felt negativity toward that.

What makes the whole process so exciting for you?

It is an art of negotiating how to get my hands on so much of these materials that are in people's lives. So it keeps me outside the studio trying to figure out who my next participants and donors are. It's a certain part of activism for me, as opposed to the lonely artist who paints away in her studio.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)