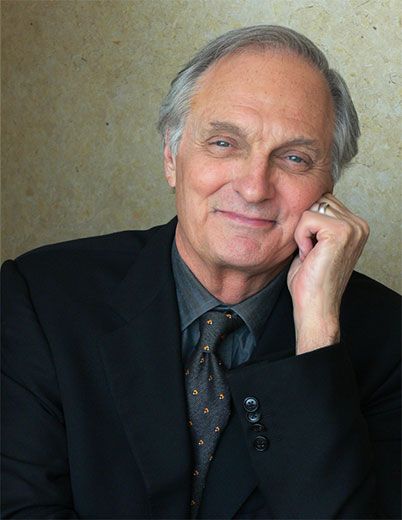

Q & A with Alan Alda on Marie Curie

A new play explains how despite the many challenges, the famous scientist didn’t stop trailblazing after her first Nobel

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Alan-Alda-Marie-Curie-Radiance-631.jpg)

After a long career in movies, theater and television shows including “M*A*S*H*” and “Scientific American Frontiers.” Alan Alda has written his first full-length play, Radiance: The Passion of Marie Curie. It debuts at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles on November 9.

What got you interested in Marie Curie?

What got me interested was that this part of her life is such a dramatic story. But what kept me interested and what kept me going for the four years I’ve been working on the play was her amazing ability not to let anything stop her. The more I learn, the more I realize what she had to struggle against, and she has become my hero because of that. For most of my life, I couldn’t say I had any heroes—I never really came across somebody like this who was so remarkable in her ability to keep going no matter what. It really had an effect on me.

How did you decide to write a play about her life?

I started out thinking it would be interesting to have a reading of her letters at the World Science Festival in New York, which I help put on every year. Then, I found out that the letters were radioactive—they are all collected in a library in Paris and you have to sign a waiver that you realize you’re handling radioactive material. I just wasn’t brave enough to do it. So [in 2008] I put together a nice one-act play about Einstein. But I became so interested in researching Curie that I really wanted to write about her in a full-length play.

What part of her life does the play focus on?

You could write three or four plays or movies about different parts of her life, but Radiance focuses on the time between the Nobel Prizes, 1903 to 1911. When she won her first Nobel Prize, they not only didn’t want to give it to her, but once they relented and decided to award her the prize along with Pierre Curie and Henri Becquerel, they wouldn’t let her get up on stage to receive it. She had to sit in the audience while Pierre got up to receive it for the both of them. It’s hard to believe.

How did Curie react?

By the time she won the second Nobel Prize, this one in chemistry (the first one was in physics), Pierre had died and she had gone into a deep depression after his death. What probably pulled her out of it was an affair with another scientist who was also a genius: Paul Langevin. The affair got into the papers and Langevin even fought a duel with the journalist who printed it, which is in the play. The Nobel committee said to her, “Don’t come to Stockholm to get your award, tell us you’re turning it down. You’re not taking it until you can clear your name.” And she said, in effect, “No, I’m coming to Stockholm, I’m taking the prize, so get ready!” So that makes a dramatic progression in her character, and it’s really nice to see her struggle through that to independence.

How much of Radiance is factual?

A surprising amount. All the characters are based on real people, but I haven’t tried to be biographical about it—except for Marie and Pierre. Other characters’ conversations are imagined based on what I know of their actions and what I’ve seen from their letters. For instance, there’s a character in the play who is a journalist who is really a combination of two journalists of the time, and when you encounter what they said in print, it’s verbatim. It’s unbelievable how vicious it is—it’s misogynistic, anti-Semitic and anti-scientific. It’s ugly.

You wrote for the TV series “M*A*S*H*” and “The Four Seasons” and movies like Betsy’s Wedding. How is writing a play different from writing for TV or movies?

My background is on the stage, so when I’d write movies, they’d be a lot like plays. On the stage, the characters express themselves more through words than images. So the arguments of the characters and the tension between characters—words have to be used to express that, and I love that about theater. I’ve stood there on stages all my life, holding the attention of the audience through the words, so I think that way.

What was your favorite moment in writing the play?

One of the most thrilling moments for me was the first time I saw the actors all in costume in Seattle at the workshop we did there. I had the same feeling today when I saw Anna Gunn come out on the stage dressed as Marie; I had to do a double take because she looked just like photographs of Marie. Best of all, she has Marie’s soul. She got inside her.

You’re very active in helping advance science communication and advocating public science literacy. How does Radiance tie in?

I really think it’s important for all of us who are just ordinary citizens to understand a little bit more about science and how scientists think. For instance, if we’re trying to protect ourselves against mistakes and overaggressive research programs that might be dangerous, it’s really important to know enough about it to ask questions that really will protect you. It doesn’t help to say, “I don’t ever intend to eat engineered food.” You’d have to give up corn and a whole lot of other things you didn’t realize were engineered.

What do you hope the audience takes away from the play?

I hope they have some feeling that she’s their hero, too. She’s such a remarkable woman.

Casey Rentz is a science writer and artist living in Los Angeles.