The Radical Conservatism of Bluegrass

At MerleFest, the banjo-pickers and guitar strummers bridge the old and new

Between the twang of the banjo and the genre’s unplugged sound, bluegrass carries the sensibility of an ancient musical tradition handed down from the distant mists of time. But in reality, the genre's only 10 years older than rock 'n' roll and was considered a radical innovation in its day. Bluegrass, as performed by its earliest practitioners, was faster, more precise and more virtuosic than any of the old-time mountain music that had preceded it.

Some folks mark bluegrass’s birth year as 1940, when Bill Monroe & the Bluegrass Boys made their first recordings for RCA. Most observers prefer 1945, when Monroe hired Earl Scruggs, whose three-finger banjo roll made the music quicker and leaner than ever. In either case, Monroe’s musical modernism proved as revolutionary in country music as the concurrent bebop did in jazz.

The progressive nature of Monroe’s music, though, was camouflaged by the conservative cast of his lyrics. His music echoed the power of the radios and telephones that were reaching into isolated Appalachian communities and connecting them to the rest of the world. His music reflected the speed of the trains and automobiles that were carrying young people out of those farms and small towns into Atlanta and Northern cities. The lyrics, though, assuaged the homesickness of those people on the move with nostalgia for a vanishing way of life.

This tension between radical music and nostalgic lyrics has pushed and pulled at bluegrass ever since. This was obvious at MerleFest, held last weekend in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, nestled in the state’s western mountains, where the early azaleas and rhododendron were in bloom. MerleFest was founded in 1988 by the legendary singer-guitarist Doc Watson to honor his son and longtime accompanist Merle Watson, who died in a 1985 tractor accident. The festival reports that they had 78,000 entries over this past weekend.

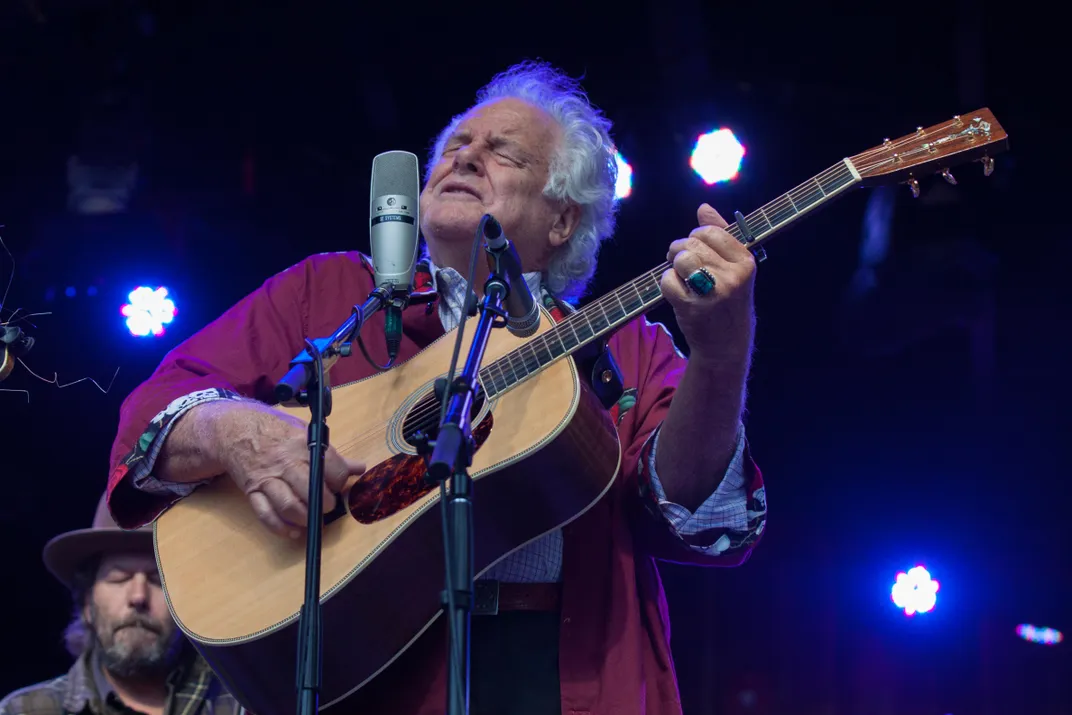

Wiry- and silver-haired bluegrass legend Peter Rowan should know, for he was one of Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys from 1965 through 1967. The fact that the Father of Bluegrass, as Monroe was known, would hire a 23-year-old kid from Boston to be his singer-guitarist revealed the old man’s openness to change—and also his crafty eye for the commercial possibilities of the emerging college audience for bluegrass. Now here was Rowan, half a century later, singing and yodeling on one of Monroe’s signature pieces, “Muleskinner Blues.” Rowan has never driven a mule team in his life, but he understands the link between hard work and suffering, and he pushed the blue notes to the foreground and made the song sound new rather than traditional.

Rowan sang “Blue Moon of Kentucky” the way Monroe first recorded it in 1946—as a melancholy waltz. Halfway through the song, however, Rowan's terrific quintet shifted into the uptempo, 2/4 version that Elvis Presley recorded in 1954. In that transition you could hear country music changing as radically as it had when Monroe and Scruggs first joined forces; Presley made the music faster and punchier still.

After the song, Rowan pointed out that Monroe incorporated Presley’s arrangement whenever he played the song after the mid-50s. “A journalist once asked Bill if he thought Elvis had ruined ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky,’” Rowan told the crowd. “Without cracking a smile, Bill said, ‘Them were powerful checks.’” It was also powerful music, and Monroe was always open to anything that would add muscle to his sound.

Not everyone in bluegrass is so open. At a lot of bluegrass festivals, you see one group after another, all dressed in dark suits and ties, all adhering to the instrumentation (mandolin, banjo, acoustic guitar, acoustic bass, fiddle and maybe dobro) and sound of Monroe’s early bands. Even when these bands write new songs, they tend to emphasize the comforting nostalgia of the lyrics over the revolutionary aggression of the music. Some of these bands are very good and serve a valuable purpose in capturing in music the longing for a simpler time, but they’re preserving only one part of Monroe’s original vision. Bands such as the Gibson Brothers, the Spinney Brothers and the Larry Stephenson Band filled this role at MerleFest. They see the classic Monroe recordings as a template to follow rather than an inspiration to change.

The Del McCoury Band had the dark suits and the classic instrumentation, and Del was once a Bluegrass Boy himself. His tall, patrician profile; his stiff, silver hair, and his “aw-shucks” demeanor make him seem conservative, but he’s always been as open to innovation as his one-time mentor. After all, McCoury’s band turned Richard Thompson’s “1952 Vincent Black Lightning” into a bluegrass hit. On Friday night, the quintet unveiled its newest project: adding new music to old forgotten Woody Guthrie lyrics, in much the same way that Billy Bragg and Wilco did on the 1998-2000 “Mermaid Avenue” albums. Because Guthrie grew up in the hillbilly/string-band tradition, the old stanzas fit McCoury’s new melodies as if they had been written at the same time.

But Guthrie’s lyrics do not look wistfully back at the past. Instead they skeptically interrogate the present and look forward to a better future. The six songs that the McCoury Band previewed from a 12-song album due in the fall took aim at cheating car dealers, greedy lovers and expensive restaurants. When Del sang “Cornbread and Creek Water,” he wasn’t praising simple country meals of “red beans and thin gravy” or “salt pork and hard biscuits”; he was complaining that the poor man’s diet wasn’t good enough for him and his family. Here at last was bluegrass with words as provocative and as rural as the music. And with McCoury’s two sons—mandolinist Ronnie and banjoist Rob—pushing the rhythm as hard as Monroe and Scruggs ever did, the urgency of the picking matched the impatience of the words.

Earl Scruggs and Lester Flatt, who left Monroe in 1948 to form their own legendary bluegrass band, were remembered at MerleFest by the Earls of Leicester, an all-star band dressed in high-crown hats and black-ribbon ties and devoted to the Flatt & Scruggs repertoire. The Earls of Leicester may well be the greatest band-name pun in modern music (rivaled only by the folk trio, the Wailin’ Jennys). Lead singer Shawn Camp imitated Flatt’s broad drawl, and Flatt & Scruggs’ longtime fiddler Paul Warren was remembered by his son Johnny, who skillfully handled his father's original violin and bow. But the band’s leader Jerry Douglas couldn’t stop himself from expanding Uncle Josh Graves’ original dobro parts into wild, jazz-informed solos, reminding everyone that the music can’t remain frozen in 1948. He suggested what Flatt & Scruggs might have sounded like if they’d been called Flatt & Graves.

Douglas sat in with Sam Bush and the Kruger Brothers at MerleFest’s Sunset Jam Friday evening. The German-born, Swiss-raised Kruger Brothers, banjoist Jens and guitarist Uwe, demonstrated how Monroe’s innovations have spread even to Europe. Their instruments chased fellow-musician Bush’s vocal around the track on Monroe’s racehorse song, “Molly and Tenbrooks.” They then proved how bluegrass can add color and drive to a country/folk song like Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee.” On Sunday afternoon, they further proved how Monroe’s music can add something even to classical music. “Lucid Dreamer,” Jens Kruger’s superb concerto for banjo, guitar, bass and string quartet, was performed by the Kruger Brothers and the commissioning Kontras Quartet from Chicago. Here was a rare instance where the fusion of two genres was founded in mutual respect and understanding, not in a desperate, gimmicky grab for attention.

Rowan roamed the festival grounds all weekend, adding his vocals to Robert Earl Keen’s set and to the Avett Brothers’ set. The Avett Brothers are the most popular of the latest earthquake in mountain music: the emergence over the past dozen years of former punk-rockers forming string bands. If Monroe’s bluegrass roared like high-powered freight trains, these bands zoom like fiber-optic internet connections. The Avett Brothers’ songwriting and arrangements are a bit too gimmicky and self-indulgent for my taste, but MerleFest also offered a blistering appearance by a like-minded but more focused band, Trampled by Turtles. Their headlining set on the big stage Thursday night seemed like an extension of everything Monroe was after: good songs set in rural America but geared up for a new era.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/geoff-vancouver-bio-lightened.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a4/9b/a49b3525-1c00-4c60-9821-cd80f94997ee/17263584752_24ec42e0b1_o.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/geoff-vancouver-bio-lightened.jpg)