What Frankenstein Can Still Teach Us 200 Years Later

An innovative annotated edition of the novel shows how the Mary Shelley classic has many lessons about the danger of unchecked innovation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/15/0815181b-10a6-4f56-9eaf-fe371038b2eb/frankenstein_pg_7.jpg)

In movies, television shows and even Halloween costumes, Frankenstein’s monster is usually portrayed as a shuffling, grunting beast, sometimes flanked by Dr. Victor Frankenstein himself, the OG mad scientist. This monstrosity created in the lab is now part of our common language. From Frankenfoods to the Frankenstrat, allusions to Mary Shelley’s novel—published 200 years ago this year—and its many descendants are easy to find in everyday language. And from The Rocky Horror Show to the 1931 film that made Boris Karloff’s career, retellings of Shelley’s story are everywhere. Beyond the monster clichés, though, the original story of Frankenstein has a lot to teach modern readers–especially those grappling with the ethical questions science continues to raise today.

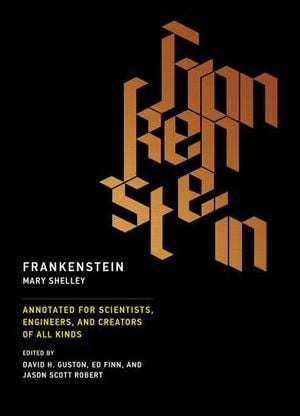

It was this idea that drove a creative new edition of the novel for readers in STEM fields. Published last year by MIT Press, Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers and Creators of All Kinds is specifically aimed at college students, but has a broad appeal to those looking to explore the past and future of scientific innovation. When Shelley published Frankenstein, it was considered a graphic book with shocking portrayals of mental illness and ethically fraught science—two qualities that lay at the heart of why the story has endured. “It is hard to talk about Frankenstein without engaging with questions of science and technology,” says Gita Manaktala, MIT Press’s editorial director. From the electricity that Dr. Frankenstein uses to animate his discovery to the polar voyage that frames the narrative, science is integral to the novel.

Then there’s Mary Shelley’s personal history, as the editors note in their introduction. When she wrote the first draft of Frankenstein she was just 19, about the age of the students this volume was intended for. She had already lost a child, an unnamed daughter who died days after her birth, fled her family home to elope with poet Percy Shelley and undergone an education far more rigorous than most women—or indeed men—of her time. But for all that, she was still very young. “If she had turned up at [Arizona State University] or any other school,” write book editors and ASU professors David Guston and Ed Finn, “she would have been labelled an ‘at-risk student’ and targeted for intervention.”

Instead, she went to Lake Geneva with Lord Byron and Shelley to engage in the story-writing contest where she composed the first version of Frankenstein, drawing on material from her education and her life experiences. Her story contains “A very adaptable set of messages and imagery, but it still has at its core this incredibly profound question, that again goes back to Prometheus, goes back to Genesis, ‘What is our responsibility for the things or entities that we create?’” Guston says. That question can as easily be examined in the context of scientific innovations like gene editing and conservation as it could in the context of industrialization and electricity in Shelley’s time.

The book’s editors wanted to tease out those questions by having a wide range of commentators– from science fiction writers and psychologists to physicists–annotate the text with their explanations and related commentary. The annotations range from an explanation of alchemy from Columbia University historian of science Joel A. Klein to an examination of technology’s place in state executions from ASU gender studies scholar Mary Margaret Fonow. This treatment “offers a really distinctive perspective on the novel and directly aims it at an audience that we think is really important to the book but that might not otherwise think that the book is really meant for them,” Finn says.

Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds (Mit Press)

This edition of Frankenstein pairs the original 1818 version of the manuscript with annotations and essays by leading scholars exploring the social and ethical aspects of scientific creativity raised by this remarkable story.

The editors also commissioned essays looking at everything from gender and nature in the book to the idea of “technical sweetness”—that is, the idea of a technical problem having an inevitable, perfect solution.

The resulting paperback is its own kind of stitched-together creature: behind a dramatic graphic cover, the reader finds many of the trappings of a traditional book, including a footnoted editors’ preface and introduction, the annotated novel, the essays, and a historical timeline of Shelley’s life. It’s still Frankenstein, one of the most commonly assigned books in university classrooms according to Manaktala, but it’s Frankenstein anatomized, laid bare on a dissection table with a number of its scientific, philosophic and historical entrails pulled out for readers to examine.

Frankenstein presents an excellent vehicle for introducing readers to a broader conversation about scientific responsibility, says Finn. In contrast to the pejorative use of Frankenstein’s name in terms like “Frankenfood” for GMOs, the novel is “actually quite thoughtful and takes a much more nuanced and open stance on this question of scientific freedom and responsibility,” he says.

“It’s a book that’s relentlessly questioning about where the limits are and how far to push, and what the implications are of what we do in the world,” Manaktala says. For students learning about subjects like gene editing and artificial intelligence, those questions are worth exploring, she says, and science fiction offers a creative way to do that.

As part of an effort to keep the book accessible to a wide scholastic audience, the editors created the Frankenbook, a digitally annotated website version of the book where they plan to expand the annotations of the print version. Hosted by MIT Press, the site also has a community annotation function so students and teachers can add their own comments.

Manaktala says the publisher is looking for other seminal works of fiction to annotate in a similar fashion, though nothing has been settled on yet. “It’s a way to keep great works of literature relevant for a wide readership,” she says. As for the annotated Frankenstein and the online Frankenbook, they remain, like the story they tell, a cultural work in progress.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.