Recalling Robert Rauschenberg

On the artist’s innovative spirit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/rauschenberg-631.jpg)

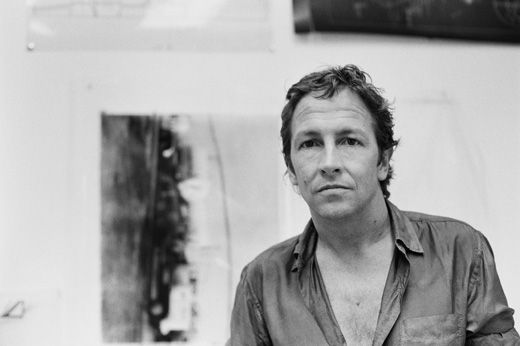

At Bob Rauschenberg's the television was always on. This was as true in the hulking former orphanage that became his Greenwich Village pied-à-terre as it was in the cottages scattered like coconuts amidst the palm groves of Captiva Island, Fla., his real home in the last decades of his life. He died last week at the age of 82, an American artist whose "hybrid forms of painting and sculpture changed the course of American and European art between 1950 and the early 1970s," according to the Los Angeles Times.

It was winter, sometime late in the 1970s, when I went to Captiva Island with Tatyana Grosman, the legendary printmaker who'd introduced Rauschenberg as well as Jasper Johns and a who's who of artists of their era to the infinitely experimental possibilities of printmaking. She and I and her master printmaker Bill Goldston settled into one of the cottages that Bob had bought from aging pensioners (to whom he offered free rent for the rest of their lives). Bob lived in another cottage, on a sandy beach. There was the painting studio cottage, the printmaking cottage, and on and on—many more now, since Bob became the big landowner on the island. We traveled between cottages under high trees on what felt like jungle paths.

Bob rose late, mid-afternoon. He'd reach for the glass of Jack Daniels which he was only without during short-lived binges of sobriety, then hang out with the menagerie of people who were usually around—friends, a lover, dealers, collectors, visitors from up North. There was plenty of laughter while someone prepared dinner, which I remember as being ready sometime around midnight. Bob held the stage with his actor's baritone and theatrical chuckle, his eyes crinkled and sharply alert. He was present and paying attention, but in the background, and under it all was the TV, its staccato images of breaking news and sitcoms blinking across the screen, carrying indiscriminate messages from the outside world.

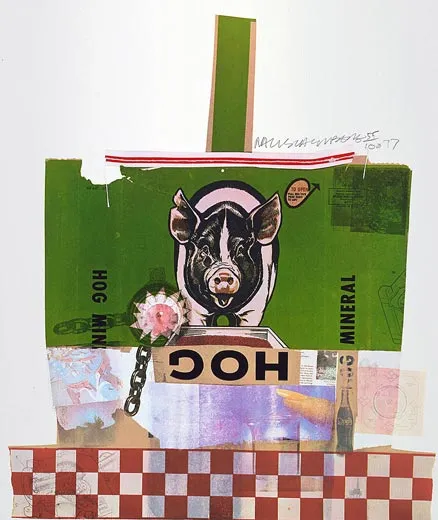

After dinner we all moved into the painting studio, where Bob literally performed his work. His art is inclusive and communal, and so was the making of it. He liked people around, a kind of audience with whom to interact, as the work became an intense version of the before dinner experience. Images not so unlike the ones emanating from the TV became patterns ordered into arcane metaphors, placed among found objects which he had taught the world were beautiful, with a grace and spontaneous exactitude that Tanya Grosman had once compared to the dance of a bullfighter.

He'd invited Tanya down on the pretext of work to be done, he confided, because he thought she needed a winter vacation. Tanya's version was that she'd gone to mother him. He had that gift for intimacy with any number of people. And all of them were always waiting to be surprised, as he had surprised the world with his reshuffling of the relationship between what was then considered High Art and the everyday life of objects and experiences. He famously said that he made art in the gap between art and life. But in his own world there was no gap between the two.

In 1963, when the lithographic stone on which he was printing cracked at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), Tanya's West Islip, N.Y., studio, he tried another stone. When that cracked, too, he had them use the stone and print the lithograph, crack and all, creating Accident, one of the most celebrated of contemporary prints and a metaphor for his art and his life.

I was there in 1978, when Tanya, who had been born in the Ukraine in 1904, introduced him to the Soviet-era poet Andrei Voznesensky, who could fill a Moscow stadium with his discretely apostate verse. The two men bonded over stories about their mothers, and then they began work on a series of prints. Voznesensky's idea of experimentation consisted of delicate riffs on the Russian avant-garde of the turn of the century. Rauschenberg turned it all upside down, inserting clutter, accident and apparent chaos. This is the way we do it here, he said.

He was working in Japan when Tanya died in 1982. He drew on an old photograph of her and printed it on a new material which could withstand time and weather, and brought it to her memorial to place on her grave. Goldston became his partner at ULAE, together with Jasper Johns, and they invited in a new generation of artists. None of them was as protean and profoundly inventive as Rauschenberg, because he had no fear of accidents or of the distraction of constantly inviting the world into his studio.