Recasting Shakespeare’s Stage

Designing a Globe Theatre for the 21st century

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/shakes_virtualglobe_388.jpg)

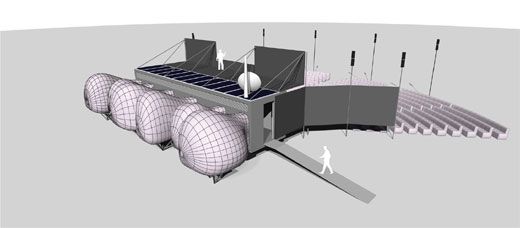

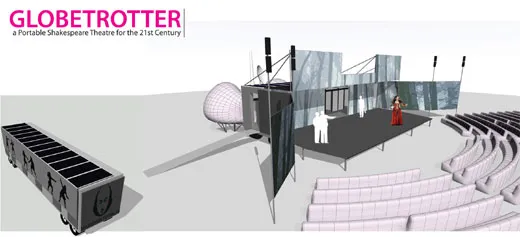

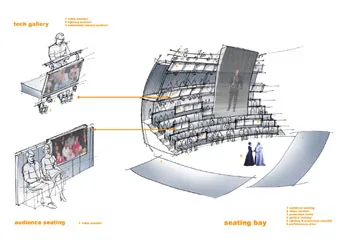

The tractor-trailer planted firmly in the Wal-Mart parking lot did not seem out of place, but the actors who performed Merchant of Venice right beside it sure did. When the vehicle arrived it deployed into a full-size stage. Behind the set, pneumatic pods inflated to become ticket-windows and dressing rooms. Sunlight powered the spotlights and speakers. And when the playhouse folded up and drove off, a screen mounted on the side of the trailer replayed the show for all to see.

This is the Globe Theatre—not the one that housed Shakespeare's best dramas, but one conceived by Jennifer Siegal for a modern audience. Siegal's Globe is part homage to the Elizabethan era's itinerant theatre troupe, part shout-out to today's compact, on-the-go gizmos. The Los Angeles-based architect was one of five designers asked to create a 21st-century Shakespearean theatre for "Reinventing the Globe," a new exhibit at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., that opens January 13 and runs through August 2007.

Given only brief guidance and a few months to finish, these architects created modern Globes that challenge conventional thoughts about dramatic performances and the spaces that accommodate them, says Martin Moeller, the exhibition's curator. "When the words stay the same but all else changes, you realize how much power the words have," he says.

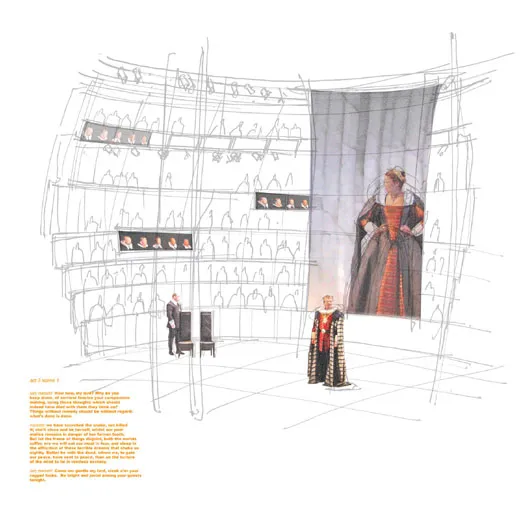

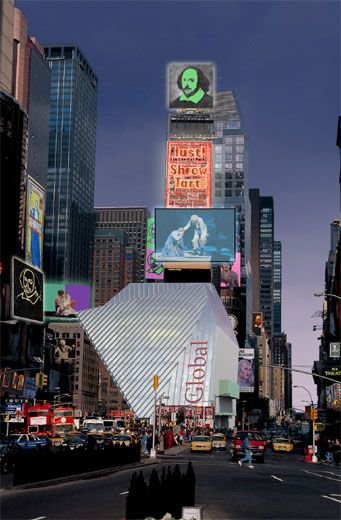

Theatre designer John Coyne delivered a truly virtual Globe. To reflect today's cross-cultural world, Coyne's performances would occur simultaneously in several locations. Gigantic screens with live streaming would hang above the stages, and characters would interact in real time. So, speaking in Russian from Moscow, Polonius offers advice to Laertes in New York; standing oceans away, Hamlet pierces Claudius with a venom-tipped sword.

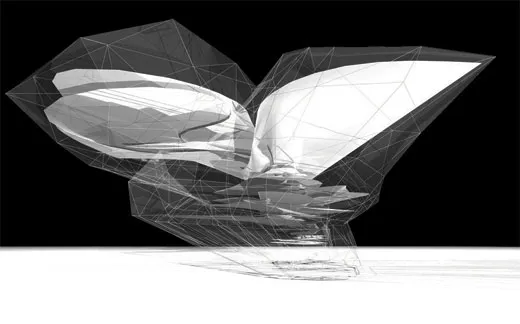

Michele (pronounced Mi-keleh) Saee, who did not have theatre design experience, modeled a Globe that would capture an actor's fluidity in the structure itself. He proposed tracing the movements of an actor throughout a performance using electronic monitors then, with the help of a computer, turning these motions into a three-dimensional image that would become the building. "It's like those photos at night where you see red and white lights streaking down the road," Moeller says. "It's almost like you have a history built into one image."

David Rockwell's transparent Globe is intended to erase the barrier between outdoor and indoor settings. H3, the architectural firm guided by Hugh Hardy, created a floating Globe that could bounce around to various New York City boroughs, like so many bar-hopping hipsters, as a way to increase public access.

Siegel, who is the founder of the Office of Mobile Design, says her portable Globe, dubbed the "Globetrotter," is ready to go into production with the right client.

"We're a mobile society that deals with communication devices in a compact way, and theatre can be represented in a similar take," she says. "It doesn't have to be going to this old, stodgy building. It could be much more accessible, transient and lighter."

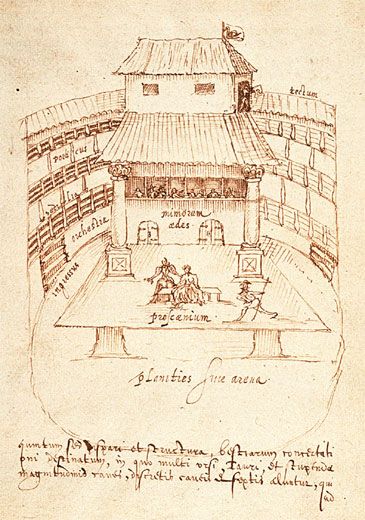

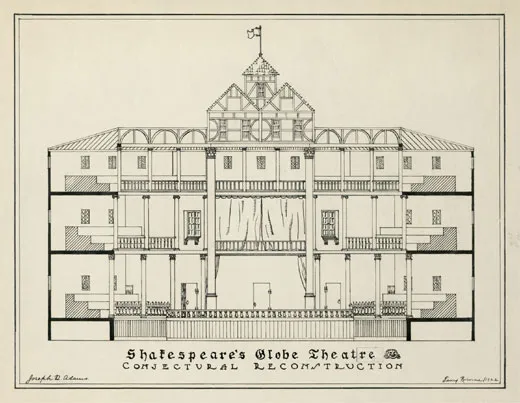

In some ways, conceptualizing a Globe Theatre for the future requires as much imagination as re-creating the one that stood in Shakespeare's day. Despite the playhouse's prominence, historians still argue over many aspects of the theatre, says Franklin J. Hildy of the University of Maryland, an advisor to the London Globe reconstruction that opened in 1997.

Notable uncertainties include the shape of the stage (some say it was rectangular, others square); how many sides the structure had (with ranges from 16 to 24); even the size of the building itself (some call the diameter 100 feet across, others 90).

Globe reconstructions work off evidence from seven maps of London in that day, texts from Shakespeare's plays and a site excavation (the original theatre, built in 1599, burned down in 1613 and was restored in the same place). Perhaps the most crucial historical document is a contract to build the Fortune theatre, a contemporaneous playhouse, which instructs builders to copy many of the Globe's dimensions.

Of the Globe's certainties, the stage that jutted out into the crowd was one of its most impressive attributes, says Hildy. "Everywhere you looked there was life, audience, energy." Standing patrons, known as groundlings, surrounded the stage, often shouting at the actors, cracking hazelnut shells—even sitting on stage.

Though Shakespeare's work also appeared at the Rose and Curtain theatres, the Globe hosted most of his famous dramas—including Hamlet, King Lear and MacBeth—which explains part of its lasting allure, Hildy says.

"The sense has always been that you could feel a closer connection to Shakespeare if you could understand how he saw theatre, how he saw his plays staged," he says. "Shakespeare was working during one of the most successful periods that theatre has ever had. There seems to be a relationship between buildings and that success."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)