The soft sunlight of a late afternoon streams into the atelier, dapples the 20-foot-high walls, and rests on a paint-stained blue smock draped over an upholstered chair. A carved oak case contains the artist’s tools: small bottles of pigments, paint tubes, palettes, brushes. Beside it is a cushioned wooden pole to support the artist’s arm when it tired.

Perched on an easel is a vast unfinished canvas, showing horses running in frantic motion. The artist, Rosa Bonheur, has filled in the animals in the foreground and some of the sky and the sun-parched ground. Horses on the periphery are silhouettes in brown. Bonheur was working on the painting at the time of her death in 1899.

The richest and most famous female artist of 19th-century France, Marie-Rosalie Bonheur lived and worked here at her small Château de By, above the Seine River town of Thomery, for almost 40 years. The atelier is a reflection of her life, frozen in time. Her worn brown leather lace-up boots, matching riding gaiters and umbrella sit on the chair with her artist’s smock. The walls are cluttered with her paintings, animal horns and antlers, a Scottish bagpipe, and taxidermied animals—a small stuffed crocodile, the heads of deer and antelope and of her beloved horse. Stuffed birds sit atop a cupboard, while a stuffed black crow with flapping wings looks as if it is about to take flight.

Next to the easel on the parquet floor sprawls the golden skin of Fathma, Bonheur’s pet lioness, who roamed freely throughout the chateau and died peacefully here. Two portraits of Bonheur look out at the viewer. In one, dressed in her uniform of a knee-length blue smock over black trousers, she poses with her artist’s palette and a painting she is working on. Her dogs Daisy and Charlie sit at her feet. In the other, she is portrayed as a young androgynous-looking woman; with the permission of Édouard Dubufe, the artist, she painted in a bull where he had painted a table. Her wire-rimmed eyeglasses rest on a low wooden desk; her sheet music sits on the grand piano. But the walls are streaked with water from a leaking roof, and horsehair stuffing spills out of some of the chairs.

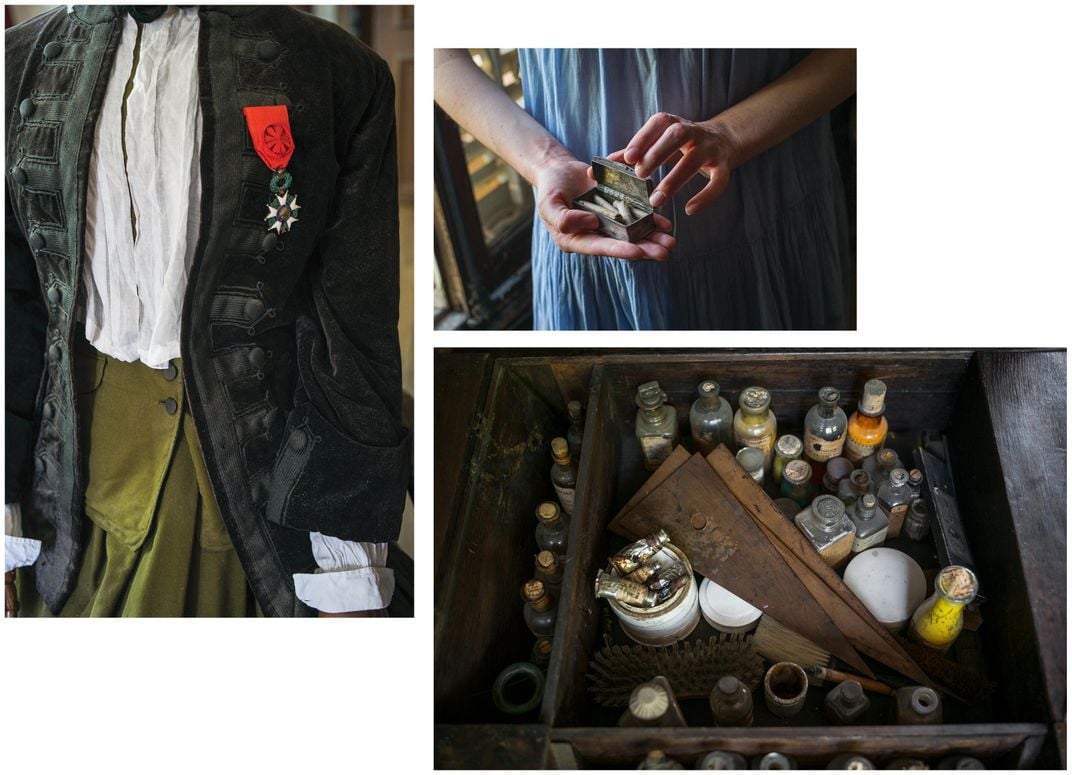

There were other female painters in her day, but none like Bonheur. Shattering female convention, she painted animals in lifelike, exacting detail, as big and wild as she wanted, studying them in their natural, mud-and-odor-filled settings. That she was a woman with a gift for self-promotion contributed to her celebrity—and her notoriety. So did her personal life. She was an eccentric and a pioneer who wore men’s clothes, never married and championed gender equality, not as a feminist for all women but for herself and her art. Her paintings brought her colossal fame and fortune during her lifetime. She was sought after by royals, statesmen and celebrities. Empress Eugénie, the wife of Napoleon III, arrived unannounced at the chateau one day and was so impressed with Bonheur’s work that she returned to pin the medal of Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur on the painter’s bosom. Bonheur was the first woman to receive the honor for achievement in the arts. “Genius has no sex,” the empress declared. (In 1894, Bonheur was raised to the rank of Officier.)

Emperor Maximilian of Mexico and King Alfonso XII of Spain also decorated her. Czar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra of Russia met her at the Louvre. Queen Isabella of Spain came to visit. Eugène Delacroix, France’s leading Romantic painter and a contemporary, appreciated her work. The composer Georges Bizet is said to have commemorated her with a cantata, although it is now lost. John Ruskin, England’s leading art critic, debated the merits of watercolors with her. A porcelain doll was made in her image and sold at Christmas. A variegated red rose was named after her.

Today she is largely forgotten. Mention her name to Parisians and they are likely to evoke the sites in the city named after her—a nightclub-boat on the Seine, a creperie in the Jardin des Tuileries, and a bar-restaurant in the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. Her chateau is not cited in most guidebooks of the area, even though the vast royal chateau at Fontainebleau, one of the country’s top tourist attractions, is only a few miles away. Her painting Haymaking in the Auvergne, in the Fontainebleau chateau, sits in a room open to the public for only a few hours a month.

But Bonheur’s legacy is now in the hands of another Frenchwoman, Katherine Brault, a 58-year-old former communications specialist who bought the chateau in 2017. With limitless passion and very little money, she is dedicating her life to painstakingly transforming the site into a museum that will honor and promote the life of Rosa Bonheur. Every day brings new discoveries of works by and about Bonheur that have been crammed into the attics and cupboards for more than a century.

Bonheur once called her art “a tyrant” that “demands heart, brain, soul, body.” The same passion could be said of Brault. “By the time Bonheur was 40, she was rich and famous around the world,” Brault said. “A woman without a husband, a family, children, a lover—imagine!” She went on, “In a deeply misogynistic century, she was a woman who had brilliant success without the help of a man. Without having been ‘the muse of...,’ ‘the wife of....’ It is my mission to restore her to the greatness she deserves. I didn’t have a choice. Really, I didn’t have a choice.”

* * *

Bonheur wasn’t destined for greatness. Her father, a struggling art teacher and artist, moved the family from Bordeaux to Paris when she was 7. There, he went to live with members of the utopian socialist Saint-Simonian movement, leaving his wife and four children to survive mostly on their own. Her mother struggled to support the family with piano lessons and sewing, but she died when Bonheur was 11. The family was so poor she was buried in a pauper’s grave. By some accounts, Bonheur vowed she would never marry and have children—a promise she kept.

A tomboy from childhood, Bonheur was called a “boy in petticoats” by her grandfather. From an early age, she focused on painting animals, which she believed had souls, just like humans. As a teenager, with training from her father, Bonheur began copying paintings in the Louvre, and she learned how to draw and paint animals in motion and with photographic precision.

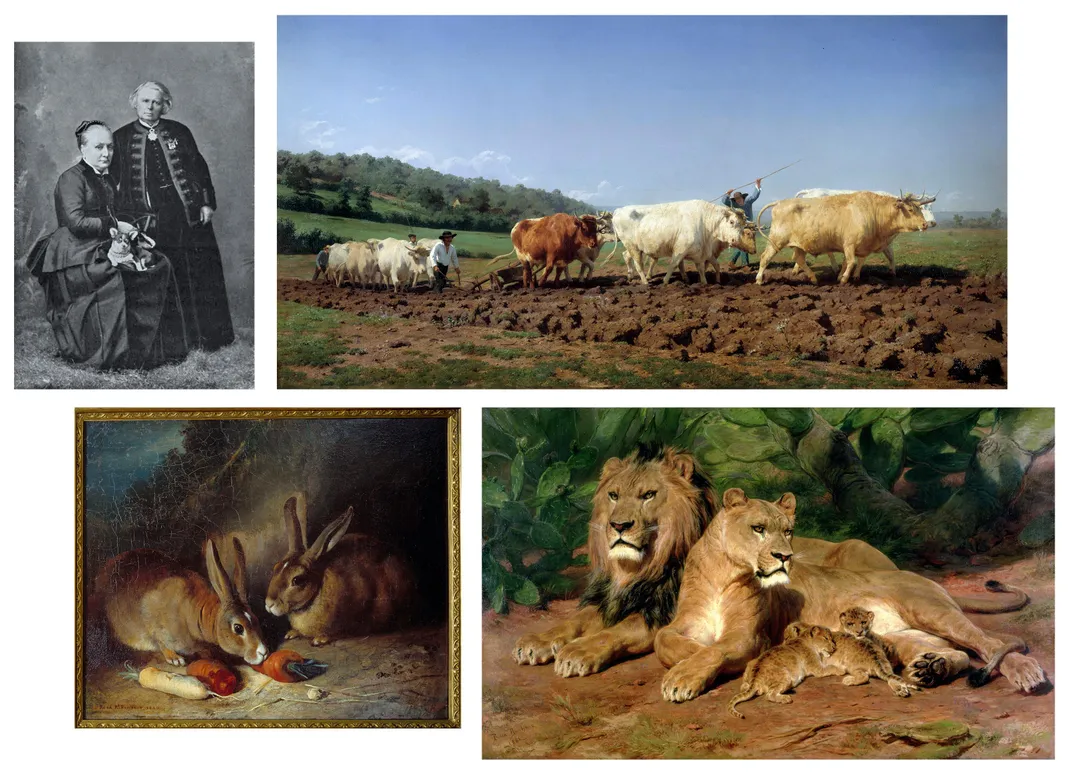

At 19, she showed two small paintings at the prestigious Paris Salon—one of two rabbits nibbling on a carrot, the other of goats and sheep. In 1848, she won a special prize from the committee that included the celebrated painters Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Soon after, she received a generous commission from the state.

The result was Ploughing in the Nivernais, a vast canvas that shows two teams of oxen pulling heavy plows during the autumn ritual of turning over the soil before winter sets in. The heroic beasts of burden dominate the painting, their white, tan and russet coats shining in the pale, luminous light. The cowherds go almost unnoticed. When it was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1849, one critic called the painting “a masterpiece.” Another proclaimed that the painting showed “much more vigor...than you normally find in the hand of a woman.” (Today it hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, in Paris, one of the few museums in France where her work is on permanent display.)

Broad-chested but small in stature, Bonheur liked to paint big. Her largest and most famous painting, The Horse Fair, measures 8 feet tall and 16½ feet wide. It shows the horse market held in Paris on the tree-lined Boulevard de l’Hôpital. The horses gallop and rear with such realism and frenzy the viewer feels compelled to jump out of the way. One American periodical called it “the world’s greatest animal picture.”

The painting caught the attention of a Belgian art dealer named Ernest Gambart, who bought it and took Bonheur on as a client. Queen Victoria received a private viewing of The Horse Fair when it was shown during a much-publicized trip Bonheur took to England. “She has taken London by storm by her skill and happy talent,” the New York Times wrote of the visit. The painting was reproduced in smaller versions and prints that were sold all over Britain, continental Europe and the United States. The original changed hands twice, then sold at auction to Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1887 for the eye-popping sum of $53,000. He immediately donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where it hangs today.

“There is something that strikes you with awe when you stand in front of this painting,” said Asher Miller, a curator in the Department of European Paintings at the Met. “There is an ambitious spirit of modernity that is undeniable and resonates today. You don’t have to know anything about art history to appreciate it. It is undoubtedly one of the most popular paintings in the Met.”

The money from the painting was enough for Bonheur to buy the Château de By, about 50 miles south of Paris—a three-story 17th-century manor house with lofts, garages for carriages, stables and a greenhouse, built on the vestiges of a 1413 chateau. She used the billiard room as her studio until she built herself the much grander atelier with floor-to-ceiling windows facing north. The chateau, built of brick and stone, was solid, if not grand. It sat on nearly ten acres of forested parkland surrounded by high stone walls and bordered the royal forest of Fontainebleau.

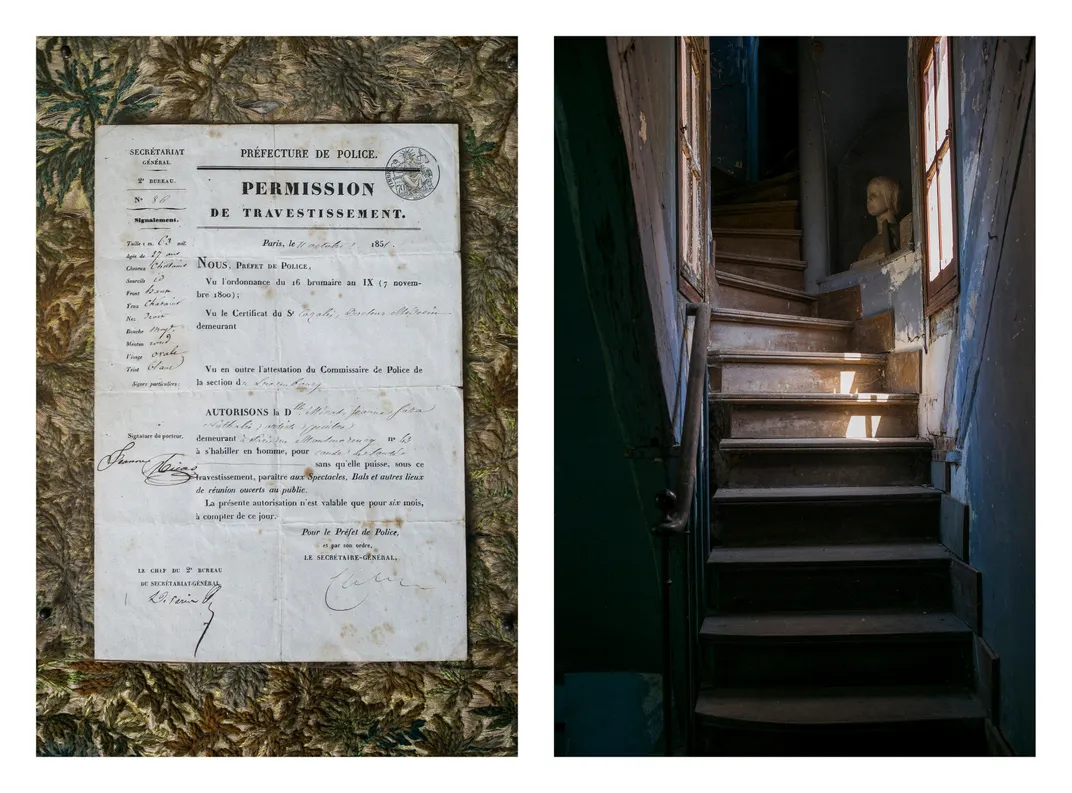

Bonheur started her day at sunrise. She went for long walks and took excursions in her horse-drawn carriage through the forest, where she sometimes painted. She kept dozens of species of animals on the property, including sheep, horses, monkeys, dogs, cages of birds, and even at times lions and tigers. She was obsessed with studying animals up close, often in all-male settings of slaughterhouses and animal fairs. That meant abandoning the cumbersome long skirts of the day and putting on pants. To do so, she received a special “cross-dressing permit” from the Paris police, renewable every six months. A copy of a permission de travestissement, filled out in longhand by her doctor “for reason of health,” hangs on the wall of the small drawing room in the chateau.

Bonheur wore her hair short, rode astride instead of sidesaddle, learned how to shoot a gun and occasionally hunted rabbits. She rolled her own cigarettes to feed a voracious smoking habit at a time when smoking was considered so degrading for women it was associated with prostitution. She cracked bawdy jokes and suffered from mood swings. She was sometimes mistaken for a man.

Asked more than once why she never married, at one point she answered, “I assure you I have never had the time to consider the subject.” Another time she said, “Nobody ever fell in love with me.” But she lived for four decades with Nathalie Micas, a childhood friend and fellow painter, who looked like a younger version of her mother, according to Catherine Hewitt, author of a 2021 biography of Bonheur.

Hewitt writes that Bonheur’s personal life exposed her to “the cruelest form of ridicule.” Hewitt herself avoids conclusions about her sex life. “That Rosa and Nathalie each represented the other’s closest relationship, there could be no doubt,” she writes. “Their affection and tender care for each other was that of a married couple....No human would ever witness what occurred between Rosa and Nathalie once their door had been pushed closed and they were alone.” Bonheur herself preferred ambiguity to clarity. At one point, Bonheur wrote of Micas, “Had I been a man, I would have married her, and nobody could have dreamed up all those silly stories. I would have had a family, with my children as heirs, and nobody would have any right to complain.”

Micas died in 1889, and Bonheur, then 67, was desperately lonely. Eventually, she invited Anna Klumpke, an American painter 34 years her junior, to live with her. Their relationship would be the “divine marriage of two souls,” she wrote in extending the invitation to the young woman, later calling her the daughter she never had. She wrote to Klumpke’s mother that her affection was “wholly virtuous,” yet in at least one letter referred to Klumpke as her “wife.” Klumpke, who wrote an authorized pseudo-autobiography of Bonheur, quoted her as saying that she swore she had stayed “pure” in her life.

What is clear about Bonheur’s relationship with the two women is that she was married, but not to them. “I wed art,” she once said. “It is my husband—my world—my life-dream—the air I breathe. I know nothing else—feel nothing else—think nothing else. My soul finds in it the most complete satisfaction.”

* * *

Klumpke brought joy and companionship to Bonheur’s later years. The younger woman played the piano and was also an accomplished portraitist, and the duo painted together. (Klumpke’s portrait of Bonheur is in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum.) As Bonheur’s health suffered and her eyesight began to fade, Klumpke stayed beside her. She cradled Bonheur in her arms as Bonheur died of pulmonary influenza in 1899 at the age of 77.

After Bonheur’s death, Klumpke became the sole heir of her estate, including the chateau and all of its contents. Bonheur’s family was shocked. “Anna was portrayed as a money-hungry American sorceress,” Brault told me. To resolve the crisis, Klumpke organized a spectacular auction in Paris that lasted more than a week—the catalog listed 4,700 items for sale—gave half the proceeds to Bonheur’s family, and bought back whatever items she could from other buyers and returned them to the chateau.

Klumpke dedicated the rest of her life to promoting Bonheur’s legacy, but Bonheur’s hyper-realistic art was already falling out of fashion. Even during her lifetime, the subject of animals never enjoyed the same status as historical art and portraiture, and her work was soon overshadowed by the formal and cultural innovations of Impressionism. “Once Impressionism pervaded people’s psyches and imaginations and became the benchmark of what was considered ‘good’ in art, much of what went before was filtered out in the eyes of tastemakers,” says Miller, of the Metropolitan Museum. “Artists were now judged and appreciated for being cutting edge in the march toward the triumph of modern art.”

Klumpke continued to paint landscapes and portraits, dividing her time between the chateau and San Francisco, where she died in 1942 at the age of 85. Over time, the Château de By fell into disrepair. Klumpke’s heirs held on, using it as an occasional residence, preserving Bonheur’s atelier and workrooms and opening them from time to time to the public.

* * *

Brault first visited Bonheur’s chateau as a child on a school outing. “We were told she was a local woman who painted, nothing about her international reputation,” Brault recalled to me. “The chateau was dusty, dark and rundown. It was scary. After that, when we’d drive by the place with our parents, we’d say, ‘Ah, there’s the witch’s house!’”

After living and working in Paris, where she had studied law and then, years later, art history at the École du Louvre, Brault returned to Fontainebleau in 2014 with the idea of creating a cultural tourism business. She visited the Bonheur chateau on a frigid January day, and with just one look at the kitchen, with its hanging copper pots and old stove, she was captivated. “I quickly felt her presence,” she said. “I had planned to find a small house. Instead, I got a big monster.”

The family was eager to sell. But the house was expensive, and Brault didn’t have the money. “Banks didn’t want to lend,” she said. “A restaurant, a creperie, a bar, yes. A museum, no. I was divorced. I had no company behind me. Some bankers would ask, ‘But Madame, where is your husband?’”

It took three years before a banker—a woman—at a small bank gave her a loan; the regional government followed with a grant. In 2017, Brault bought the property for about $2.5 million. Klumpke’s family agreed to be paid in installments. “I had to prove that this was not just the dream of a crazy woman,” she said.

The heating, electrical and water systems were old but intact. She made only the essential repairs. A year later, she opened the site to visitors. But she has struggled to raise the money for needed repairs. Most urgent were the leaky roofs, which were causing the walls to crumble. She applied for financial help under a governmental program that uses profits from a national lottery to help preserve the patrimoine, or heritage, of France.

Stéphane Bern, France’s best-known creator and host of radio and television shows on France’s cultural heritage, was seduced. “The minute the dossier arrived, I said to myself, ‘Ah, this is for us, we can help!’” he told me. Bern discovered that Bonheur’s paintings hang in the Prado in Madrid and the National Gallery in London as well as museums in the United States. “There’s a French expression: You are never a prophet in your own country. To think that Americans know Rosa Bonheur better than we do—incredible, what a scandal!”

The lottery awarded Brault €500,000, about $590,000. Not only that, but Bern persuaded first lady Brigitte Macron to visit with President Emmanuel Macron. “I told her that Rosa Bonheur was the first woman artist to receive the Legion of Honor and that the Empress of France had said, ‘Talent has no gender,’” Bern said. “Isn’t that the most beautiful declaration of equality?”

The Macrons, joined by two ministers and Bern, delivered the check personally to Brault in September 2019. They toured the chateau and walked through the garden and the adjoining woodlands. “We are entering the life of Rosa Bonheur,” Brigitte Macron said during the visit. “What an incredible woman, just like Katherine Brault. They found each other.” The president praised Brault’s courage, saying, “You have to be crazy to do what you do.”

Brault runs the chateau with the help of her three adult daughters. In addition to the atelier, other rooms have been preserved exactly the way they were upon Bonheur’s death. Brault showed me the small, semicircular second-floor salon off a winding wooden staircase where Bonheur received most of her visitors, which is anchored by a desk with a foldaway typewriter. A glass-doored cupboard contains mementos of her everyday life: colored Baccarat drinking glasses, large white teacups and saucers, several of her cigarette butts in an ashtray, and a scrapbook with comic-book-like caricatures.

An adjoining room where Bonheur did the initial studies for her paintings contains a glass-doored armoire with an authentic costume of Rocky Bear, a chief of the Oglala Sioux tribe, given to her by William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody, whom she befriended when he performed his “Wild West” show in Paris during the Universal Exposition in 1889. The pants are in orange suede, the embroidery-trimmed, fringed shirt in yellow and turquoise, the sleeves adorned with feathers. Bonheur visited Buffalo Bill in his encampment, and she sketched the Native Americans who had traveled with him to France. He came to see her at her chateau, where she painted him seated on his white horse; the painting hangs today in the Whitney Western Art Museum in Cody, Wyoming. In the same room is a seated mannequin wearing the outfit Bonheur donned when she dressed like a woman: a lace-trimmed, military-style black jacket, with matching waistcoat and skirt, to which her Légion d’Honneur cross is fixed.

Outside is a large garden bordering woods filled with elm, beech and oak trees, some of them hundreds of years old. There are vestiges of the stone basins Bonheur built where her animals could bathe and drink, and a wooden wall that she used for target practice. A tiny crumbling stone building with traces of painted murals on the walls dates from the 18th century. It was here that Bonheur would come to study her animals up close.

In the chateau, Brault has created a room painted in celadon green and brick red where tea and cakes are served to visitors on old mismatched bone china. Paying guests can stay in the large bedroom where Bonheur slept; two large halls can be rented for conferences and weddings, although such bookings have been canceled or delayed until next year because of the coronavirus pandemic.

One of the walls of the chateau is covered in metal scaffolding: A roof is undergoing major repairs. A greenhouse is awaiting restoration. The spaces open to the public show just how much work there is to do, with cracks in plaster walls, hooks with nothing hanging on them, outdated lighting, slivers of wood missing from the old parquet floors.

Leading visitors on a recent tour of the chateau, Lou Brault, Katherine’s 26-year-old daughter, answered questions about Bonheur’s art and life, and why she fell out of favor. She said Bonheur had not supported a painting school or aligned herself with any artistic movement, such as the Barbizon landscape painters who also worked in the Fontainebleau forest. Bonheur was also eclipsed by Impressionism. Paul Cézanne savaged her painting Plowing in the Nivernais, saying, “It is horribly like the real thing.”

“I always get a question about her sexuality,” Lou Brault said. “And I respond, ‘It’s not so easy to say. There are doubts.’”

The French Ministry of Culture takes a definitive stance on the subject. Its entry on Bonheur says, “If today her work has fallen into oblivion, she is remembered as one of the figures of the homosexual and feminist cause.”

* * *

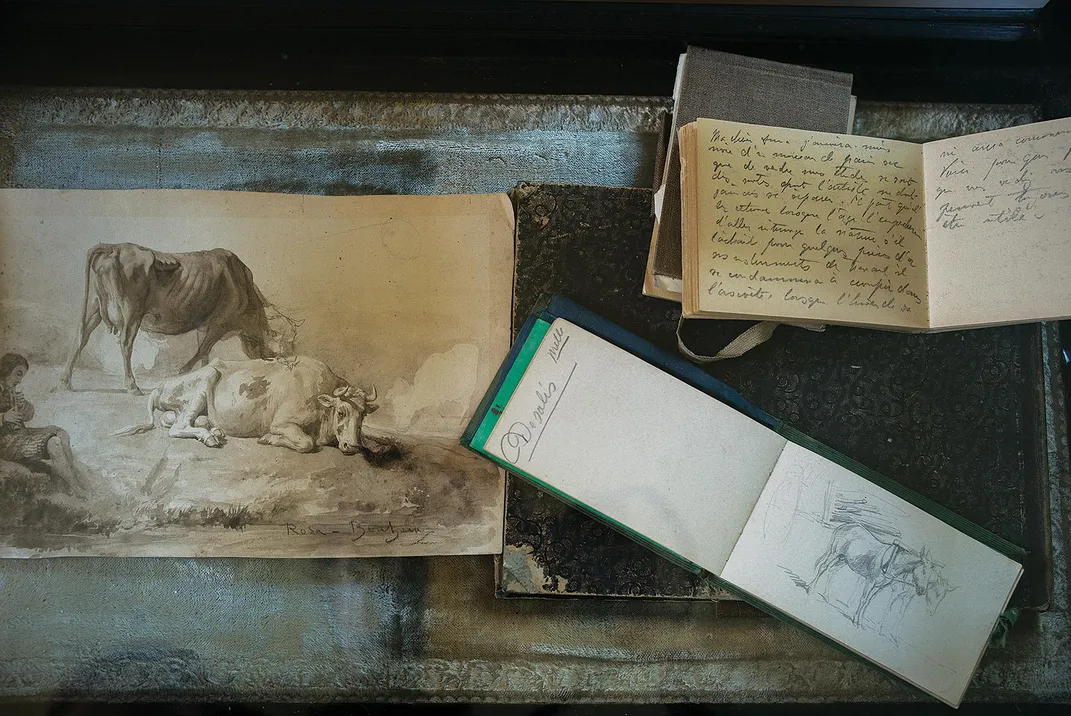

When France went into lockdown during the early stages of the pandemic, Brault transformed months of confinement into a treasure hunt. She told me that the four attics on two floors became an obsession. Clutter lined the floors; dust choked the air. She threw out debris, opened boxes, sifted through heavy-cardboard portfolios, lined up framed drawings and engravings leaning haphazardly against the walls. “I went in day after day, losing track of time, not even stopping to eat or drink,” she said. She donned a miner’s lamp so she could work in the attics at night.

During my visit, Brault and I mounted narrow staircases and entered the unlit spaces, which smelled of decades of dust. She showed me some of the treasures she has uncovered: paintings, sketches, auction catalogs, news clippings, books, notebooks, account records, photographs, letters and other writings, plus bits of lace, embroidered ribbon and decorative buttons from Bonheur’s clothing. She opened a box to reveal an enormous, white, realistically detailed plaster head of a lioness sculpted by Bonheur.

One scrapbook was filled with dozens of Bonheur’s humorous caricatures, so unlike the earnest and realistic animal paintings that they feel as if they could have been drawn today. Another box contained a study for a landscape painted on wood, still another a pencil portrait of Bonheur’s mother. Brault showed me a pile of drawings of donkeys and sheep found under a stack of china plates. In an adjoining room, cardboard boxes were filled with envelopes holding thousands of glass photo plates, awaiting identification and organization. Passionate about early experiments with photography, Bonheur had built a darkroom for herself.

Brault estimates there are more than 50,000 works of art, objects and documents in the chateau. She has dedicated two rooms to studying and archiving the old and the newly discovered works. Scholars and art historians have been invited to visit and work in the archives. A new edition of Klumpke’s “autobiography” of Bonheur and a catalogue raisonné that will list all of her works are underway. Twice a week, Michel Pons, a self-taught historian who lives nearby, comes in to work on the archives. He recently published a short illustrated book on the genesis of The Horse Fair, incorporating the studies and sketches found at the chateau.

“We are seeking patrons to help us develop conservation areas, archive consultation rooms and residences for researchers,” said Brault.

Last year, the Musée d’Orsay featured a small exhibition of Bonheur’s little-known caricatures. Isolde Pludermacher, chief curator of paintings at the museum, told me she is seeing signs of renewed interest in Bonheur’s work. “We are discovering new things about her that have so much resonance today,” she said. “It’s time to study her in a new light.”

“Rosa Bonheur is being reborn,” says Lou Brault. “She is finally coming out of the purgatory into which she was unjustly thrown.”

Her mother takes me back into the atelier. “I was all alone, cleaning out the attics one day, and I found this,” she says, holding a ten-foot-long roll of heavy paper. She lays it on the floor, and slowly unrolls it. It is a preparatory work in charcoal, featuring a man on a rearing horse, and a very unusual figure for Bonheur: a woman smack in the center, on horseback, riding so fast that the scarf covering her hair blows in the wind. I am one of the first outsiders to see it. “It took my breath away,” says Brault. “I was like an excited child. I yelled for my daughters to come quick.” Lou says, “We were screaming with joy.”

Brault has one more thing to show me: a photograph of Bonheur, seated, in her artist’s smock and pants. She is holding a large white teacup in her hands, one of the teacups that sits in the cabinet in her study. “My daughters and I are tea drinkers, and suddenly, it brought her into our family,” said Brault. “She made her presence known. I sometimes have the impression that she is talking to me. I hear her voice telling me: Try harder. You haven’t tried hard enough.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/c6/fdc631bd-92f2-4a7e-a772-3b06d20b3b3a/mobileopener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/73/56734683-4ec7-4663-9882-6bfb43182c25/opener.jpg)