Reliving the Ebony Fashion Fair Off the Runway, One Couture Dress at a Time

An exhibition on the traveling fashion show memorializes the cultural phenomenon that shook up an industry

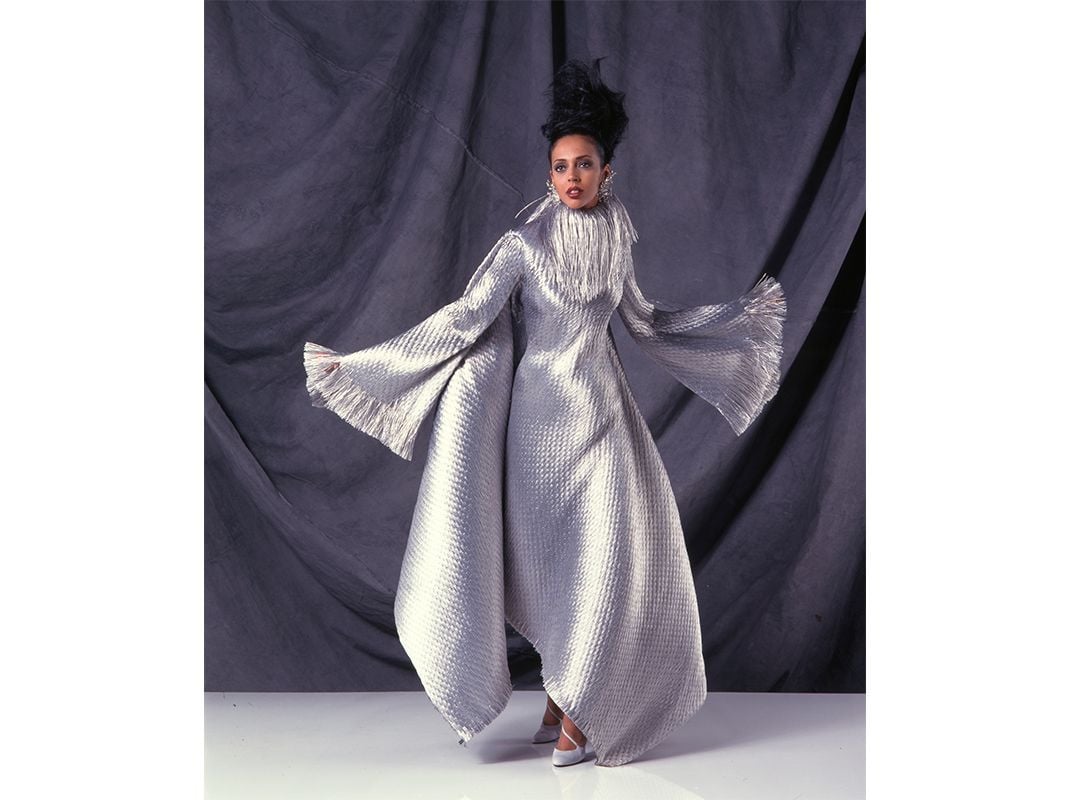

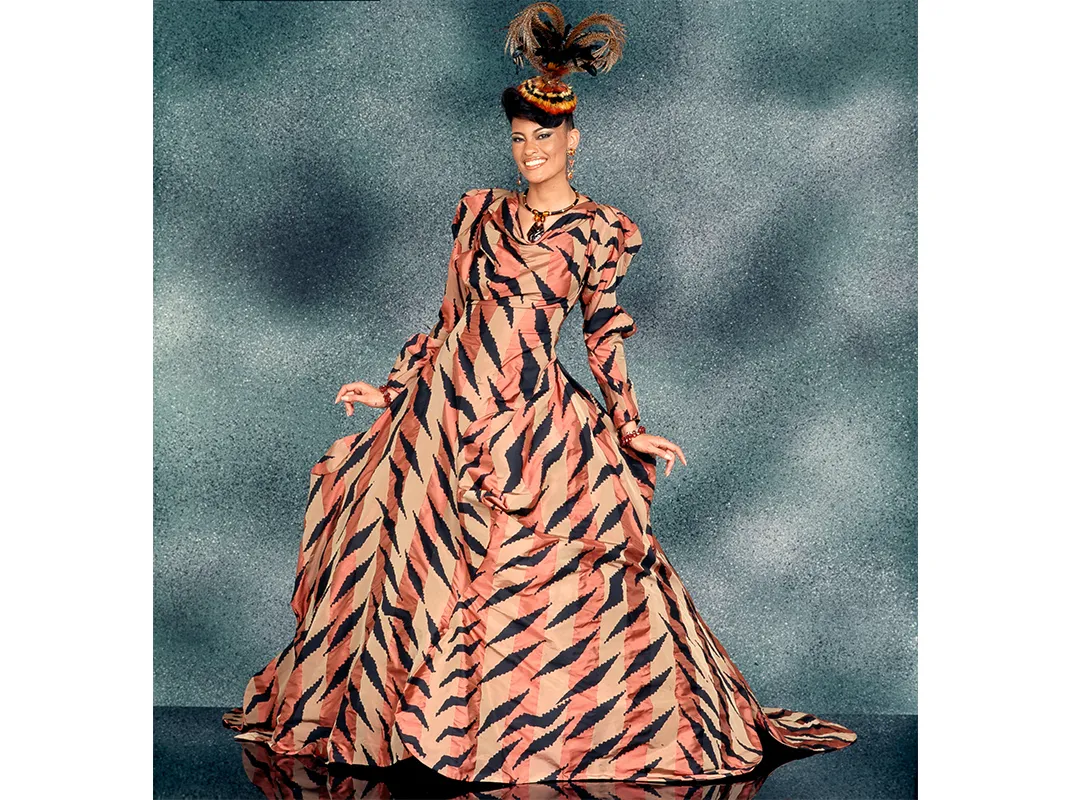

For more than 50 years, a group of African-American models traveled the country by charter bus, bringing haute couture to the masses. They walked the runway, donning outfits from the likes of Yves Saint Laurent and Givenchy, gowns that cost thousands of dollars. These women were a part of the Ebony Fashion Fair, the first fashion show to employ African-American models, shaking up the industry and becoming a cultural phenomenon in the process.

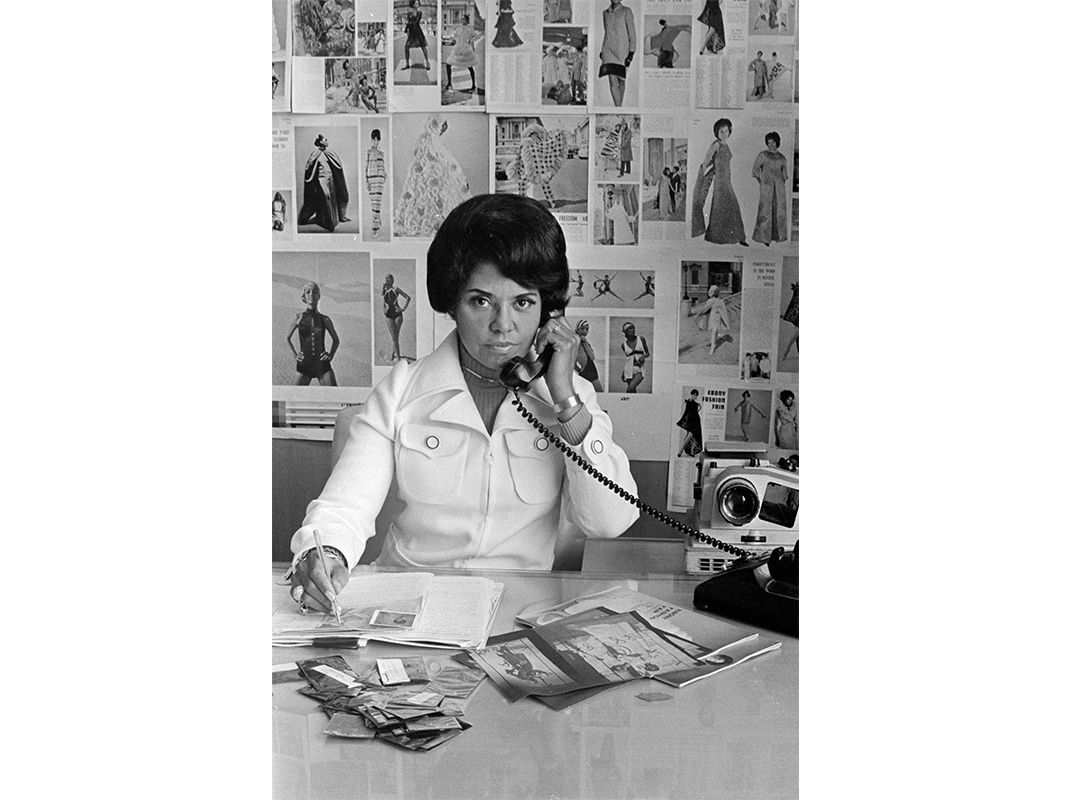

Each year, the models racked up miles performing in more than 180 cities a year in the United States, Canada and the Caribbean, traveling six days a week. And it was much more than a fashion show. Founded by Eunice W. Johnson, of the Johnson Publishing Company, the Ebony Fashion Fair became a galvanizing event known for its live music and choreographed dance numbers, raising $50 million for charities and scholarships over its multi-decade run.

Now, the first-ever exhibition on the show, “Inspiring Beauty: 50 Years of Ebony Fashion Fair” is crisscrossing the country much like the models who gave it life. The traveling exhibition’s most recent stop is at the George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C. It tells the story of the trailblazing show through 40 garments selected from a collection of thousands by designers including Christian Dior, Vivienne Westwood and Naeem Khan, who dressed former first lady Michelle Obama on several occasions.

The exhibition emphasizes “the notion that black is beautiful even before that was a movement in the 1960s,” says Camille Ann Brewer, curator of contemporary art at the museum. That empowering notion is what inspired Eunice Walker Johnson, who co-founded the company that publishes Ebony and Jet magazines, to launch the show back in 1958.

The show’s namesake was a section in Ebony, the magazine about African-American life that Johnson’s husband, John H. Johnson, founded in 1945. The very first show was intended to be a one-time event. At the request of a friend, Eunice organized the show as a fundraiser for a hospital in New Orleans. But the show's success convinced the Johnsons to take it to 10 other cities that year, and for the next 50 years, the show sold out venues across the country. The show presented a new narrative for the African-American community, allowing black Americans to see themselves represented in an industry that excluded them. Each ticket for the show came with a subscription to the magazine or its sister publication, Jet.

In the pages of her magazines and in the fashion fair, Johnson dressed her darker-toned models in the collection’s brightest fashions. Instead of shying away from dark skin like others in the fashion industry, she wholeheartedly embraced it.

Though they sold out venues across the country, the models and their show were not always welcomed with open arms. In cities where Jim Crow laws reigned, their white bus driver carried a pistol. Sometimes they would assign the lightest-skinned model in the group, who could pass as white, the task of walking into stores to purchase snacks for the rest of the bus. And, in the late 1980s, the Ebony Fashion Fair received a bomb threat before a show in Louisville, Kentucky.

When it came to acquiring the latest in European fashion, Johnson was one of the pros. As she traveled to the world’s fashion capitals, she carved a place for herself in the insular community of fashion, sometimes pushing her way past those who tried to keep her out because of the color of her skin. “In his memoir, John H. Johnson writes that at first, Eunice Johnson had to ‘beg, persuade and threaten’ European designers to sell high fashion to a black woman," notes NPR. Johnson eventually became one of the world’s top couture buyers, purchasing an estimated 8,000 designs for the show over the course of her life.

Shayla Simpson, a former model and commentator (a narrator, essentially) for the show, traveled with Johnson to Paris, Rome and Milan to select designs for the Fashion Fair. At one point, when she asked Johnson about her budget, she recalls Johnson uttering, “Have I ever told you there was a limit?”

But Johnson’s runway wasn’t reserved exclusively for the big European ateliers. Just as she opened the doors for African-American models, she highlighted the work of African-American designers, too. At Johnson’s shows, work by black designers including Stephen Burrows, known for using red piping in his color-blocking technique, made its way down the runway. (One of Burrows’ dresses is part of the exhibit.)

The groundbreaking nature of the Fashion Fair extended beyond just clothing. In 1973, they expanded the brand’s reach to a makeup line for African-American women after Eunice observed her models mixing foundations to suit their varying complexions. Though Fashion Fair cosmetics are perhaps less necessary today as more brands diversify their color options, they remain a staple of African-American beauty culture. Most of the Ebony Fashion Fair models embodied the tall, thin look typical to their industry, but the Fair also was ahead of the industry by hiring some of the first plus-size models.

Despite the limitations it faced over the decades, the Ebony Fashion Fair only came to an end when the Great Recession forced the Johnson Publishing Company to cancel the show’s fall 2009 season. And, by that time, its relevance in the fashion world had already begun to wane as the mainstream fashion industry finally began to embrace African-American models and designers.

Ebony Fashion Fair may be over for now, but “Inspiring Beauty” solidifies the show’s legacy. Along the way, it breathes new life into artifacts from a cultural phenomenon that empowered generations of African-Americans—and inspired them to embrace their beauty.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)