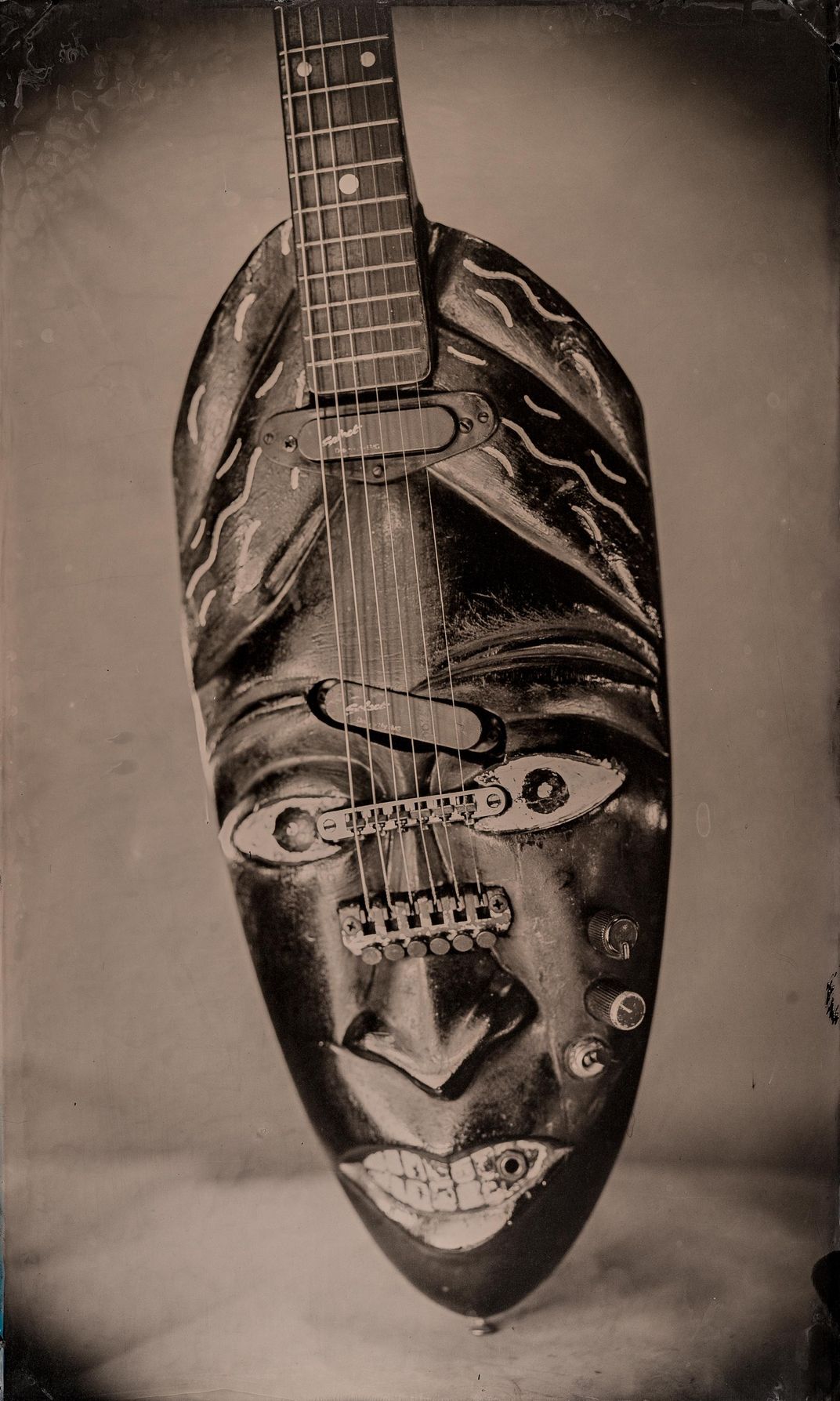

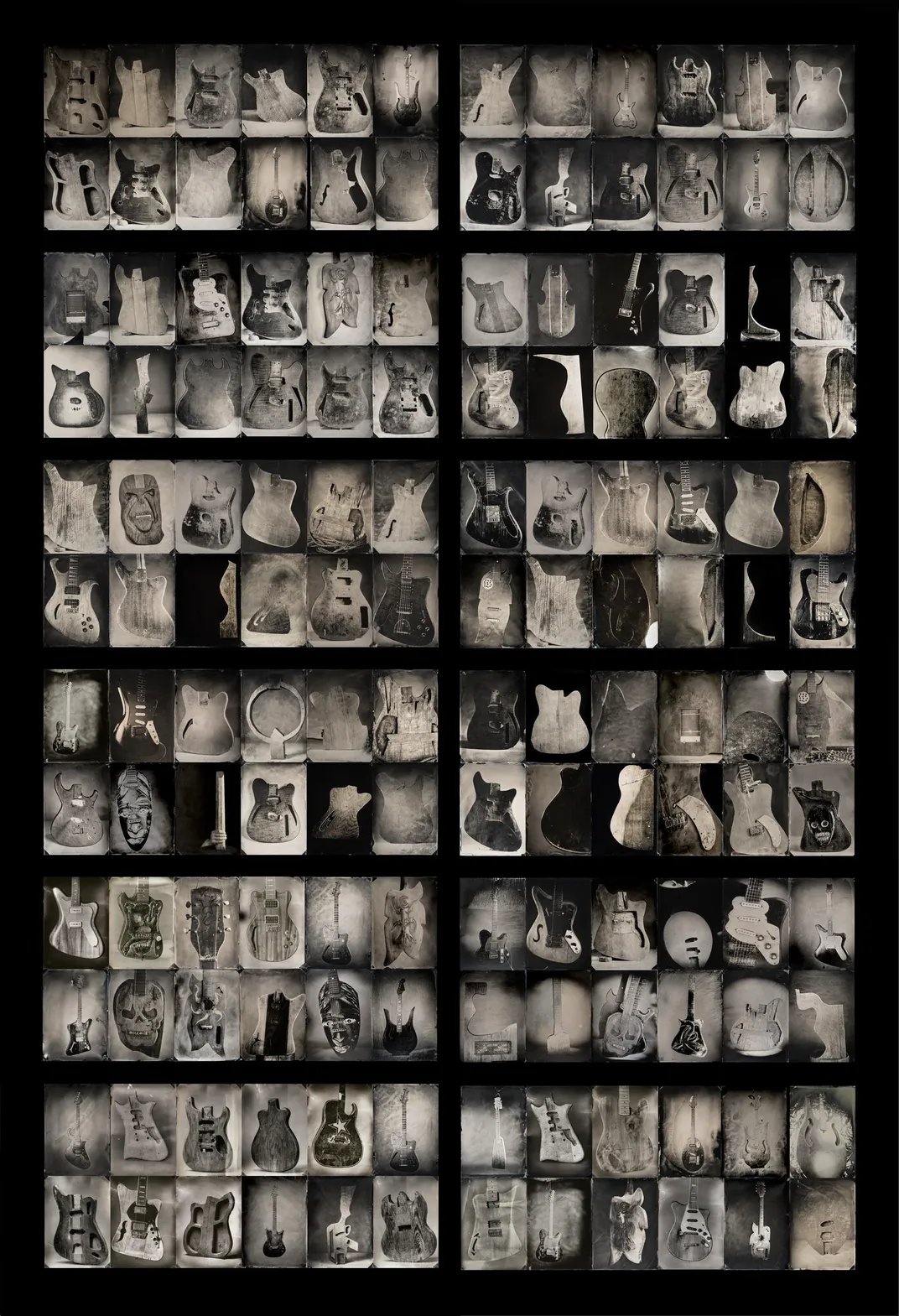

Freeman Vines has spent almost half a century creating the most distinctive guitars in America. No two look or sound the same. A few of the 78-year-old’s guitars are carved to look like African masks; others partake in the famously boxy Bo Diddley style, and others resemble nothing so much as the leaf off a tree, or the flat part of a well-used oar. For materials, Vines works with wood salvaged from unlikely places: the soundboard of a discarded piano, the front step of an old tobacco barn, the plank from a mule’s trough. Vines is on a quest. He’s trying to build a guitar with an eerily perfect tone that he first heard as a young man, and which he hasn’t been able to wring out of any of the dozens of guitars he’s crafted.

“It’s a tone where you become part of the sound—it turns you into a part of the music, like a string vibrating,” he tells me during a Zoom call from his home, which he shares with an unspecified number of dogs and guitars, in eastern North Carolina, the same area where his family has lived ever since they were enslaved.

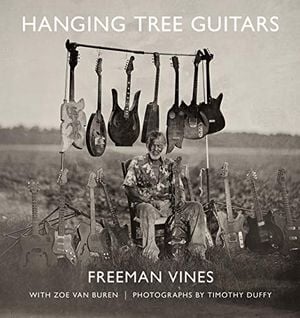

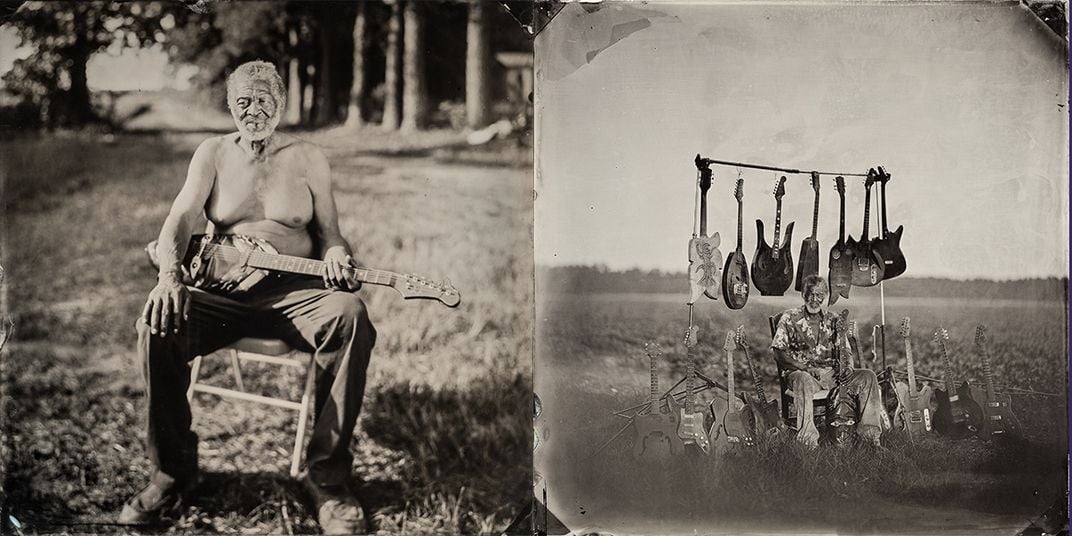

Now, with coauthor Zoe Van Buren, who serves as folklife director at the North Carolina Arts Council, Vines has released Hanging Tree Guitars, an impressionistic memoir with photographs by Timothy Duffy, founder of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, who spent five years chronicling Vines’ process. Duffy’s remarkable photographs take up roughly half of the book, interspersed with detailed storytelling from Van Buren, snippets of conversation between Duffy and Vines and prophetic-sounding soliloquies from the veteran luthier. The book is packed with fascinating details about Vines’ idiosyncratic approach to guitar-making, and about his early life in Jim Crow North Carolina, where a legacy of racist violence shaped his view of the world, and continues to exert a deep influence over his guitar designs.

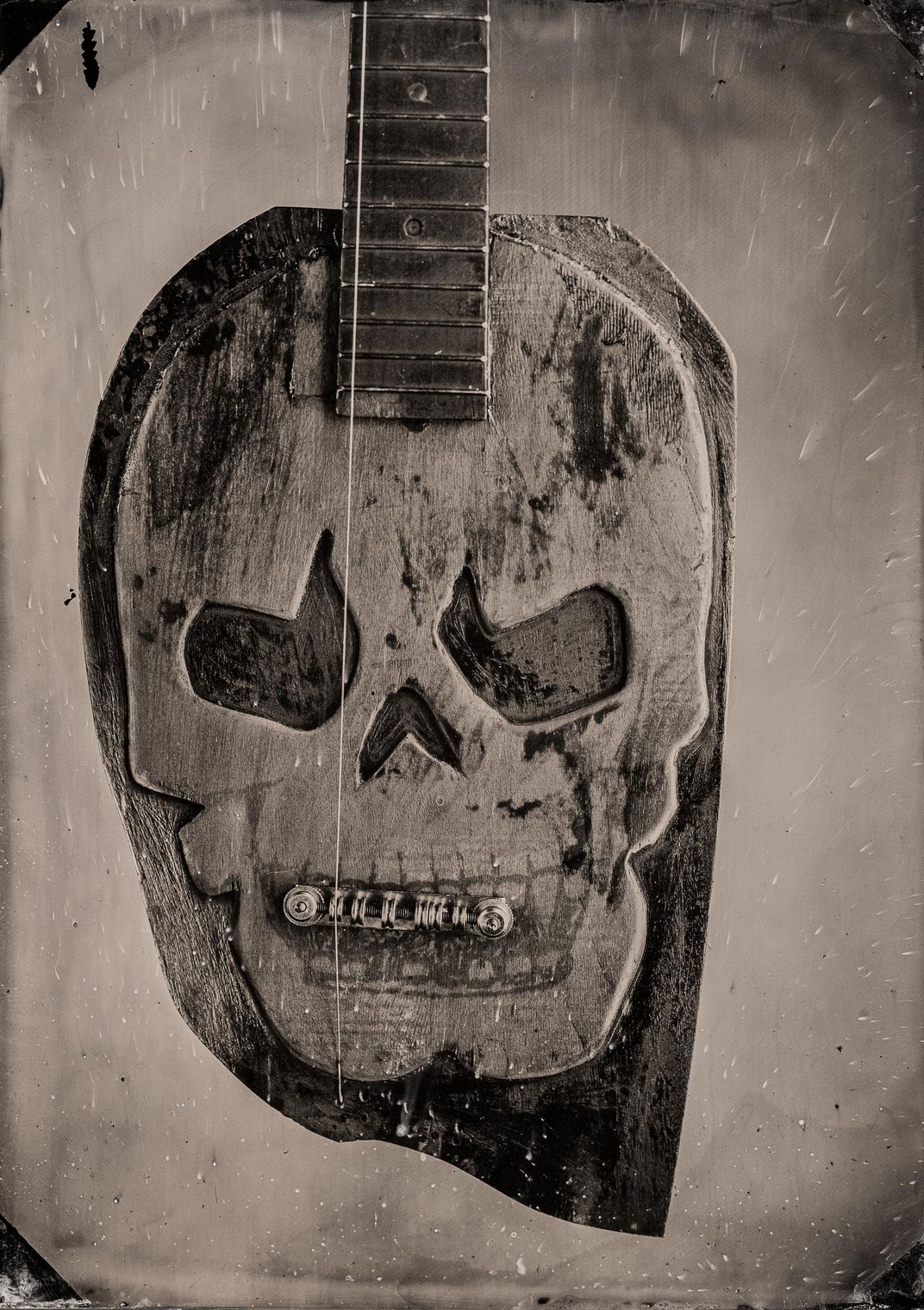

Perhaps the most notable found wood that Vines has used in his instruments comes from a black walnut “hanging tree” that used to stand a few short miles from Vines' current home. Vines has now turned its wood into four guitars.

“More than one man had been hung on that tree,” Vines writes early in the book. “Who they hung, or how many they hung, I don’t know.”

Vines grew up in Greene County, North Carolina, and worked on a plantation under Jim Crow for poverty wages on a good day. Sometimes he received no wages at all: “You go to the white man and ask for some doggone money, you’d get your head busted open,” Vines recalls in the book. Somewhere in those early days, perhaps from a guitar played at church, or an animal howling at night outside his window—Vines can’t quite recall—he heard the timbre that he would spend his life trying to elicit from the guitars he builds.

For a period, Vines toured as a guitarist with various artists on the famed Chitlin Circuit, and has played many shows with gospel groups such as the Blind Boys of Alabama and the Vines Sisters. He also did a little prison time here and there—the longest spell was in the 1960s, for moonshining—and has practiced witchcraft, particularly during the years he lived in rural Louisiana. But otherwise he’s spent his life looking for the wood that will give him the special sound he’s been seeking so long .

When Duffy first visited Vines, in 2015, Vines was considering quitting his guitar-making work on account of his diminishing eyesight and the swelling and pain in his hands that wouldn’t go away. Duffy began visiting every other week, sometimes more often, for five years, to document Vines’ process—and to marvel at the beauty of the guitars. “The wood itself was alive with its exposed texture,” Duffy writes in the book. “They were unpainted, and the wood grain of each body was as singular and varied as skin.” Vines, for his part, drew energy from Duffy’s presence. His eyesight and joint pain persisted, but instead of quitting the luthier game, he ended up embarking on one of his most ambitious projects yet: building the hanging tree guitars.

Duffy and Vines grew close, and Duffy canvassed local white families to learn more about the tree that Vines had wrought into those four guitars. Eventually, Duffy got the answers: In August 1930, Oliver Moore, a 29-year-old black tenant tobacco farmer was accused of molesting two of his white boss’ daughters and imprisoned in the Edgecombe county jail. Soon after, 200-odd white men kidnapped Moore from the prison, carried him to a spot near where Wilson and Edgecombe Counties meet and hanged him while shooting over 200 bullets into his body.

“Two hundred damn people to kill one man,” Vines writes after learning Moore’s story.

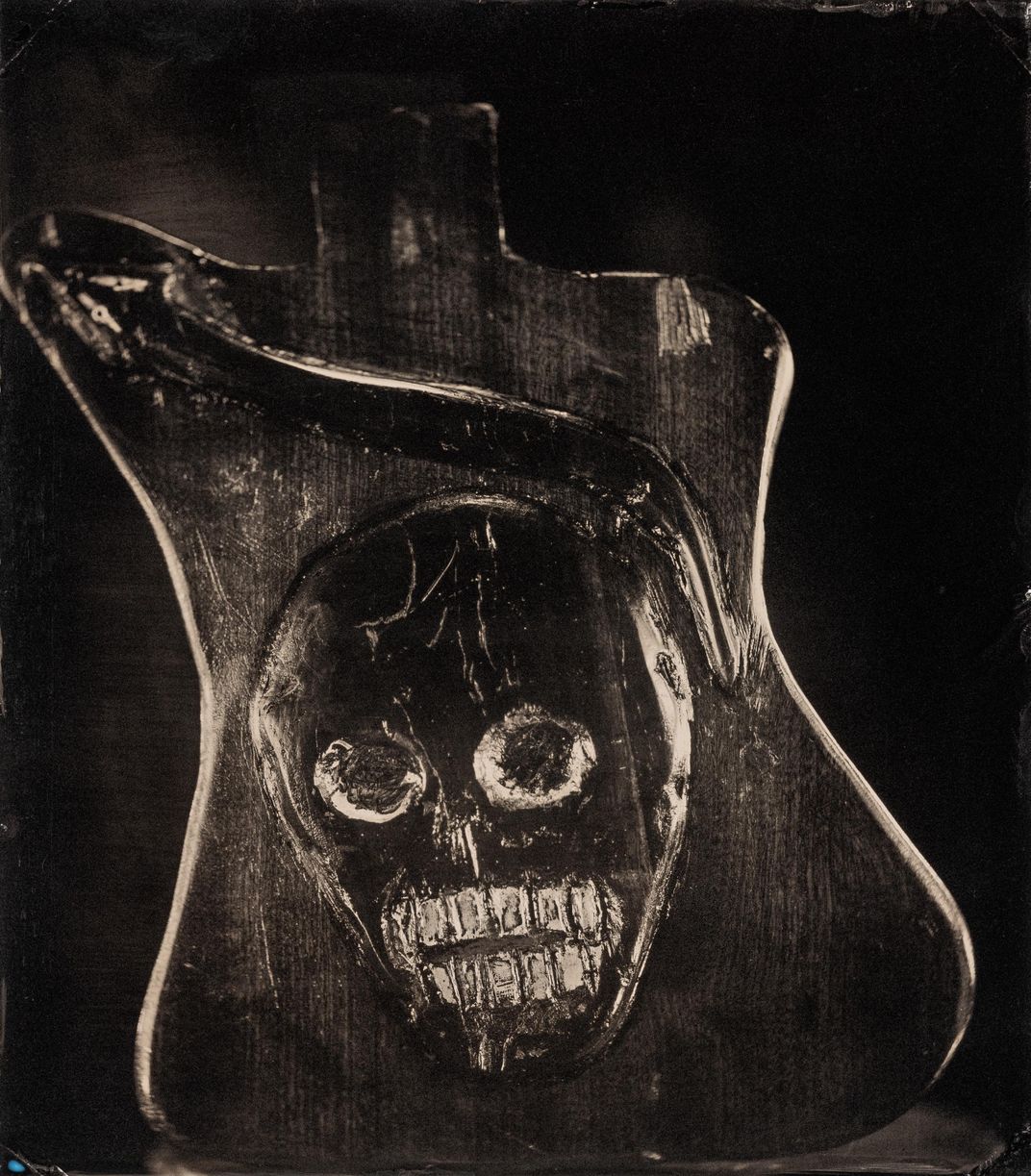

Following the Moore revelation, Vines’ guitar designs took a grimmer turn, as Van Buren, Vines’ coauthor, notes: “A series of guitars with haunting skull and snake imagery followed the revelation.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/cd/96cde965-beff-4740-bbad-b6de1497e185/celtic_hollowbody_1974.jpg)

Of the resulting photographs, Duffy would say: “I attempted to capture the horror Freeman felt from the blood that was in that wood. Of course, it is in the wood. It terrifies me.”

When I ask Vines what it feels like to play the guitars from that black walnut, Vines recalls that “the sound was awesome” when they first put one of the instruments through an amplifier. It’s “something strange and supernatural,” Vines says, as though the wood itself is trying to tell you a story when you pick on the strings. (Like nearly all of Vines’ creations, the hanging-tree guitars are not for sale, though if you visit Vines’ workshop, he might let you strum one.)

Despite the swollen hands, the dwindling eyesight and the ghosts who can’t stop tugging on his sleeve, Vines is playful and gregarious in conversation, clearly energized by the new book, and by the new guitars that he’s been making. Collectors looking to buy a Freeman Vines original won’t have much luck if they show up on his property; he tends to turn away prospective buyers even when they make the pilgrimage. Still, those curious still have ample opportunities to inspect Vines’ work. A selection of his guitars went on view earlier this year at a gallery in Kent, England, and while Covid-19 has delayed the stateside exhibitions meant to accompany the release of the Hanging Tree Guitars book, the Music Maker Relief Foundation has created a digital exhibit of Vines’ work. Now, people all over the world can marvel at the instruments crafted by this singular man, and how each of his creations seems to embody a dance between life and death.

Toward the close of Hanging Tree Guitars, Duffy asks Vines: “Do you think the spirits are in the hanging tree wood?”

Vines responds: “You know they are. They’ve got to be. They’ve got nowhere else to go.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/3a/543a20c7-881d-4641-90c2-a26b80d4253f/mobile-hands-guitar.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/88/47/8847ac92-6b3c-4cca-a574-6699289b2bdf/opener-ted-piece.jpg)