Remembering the “Eclectic Gusto” of Architect Hans Hollein

A look into what still excites us about the Viennese designer, who died last week at 80

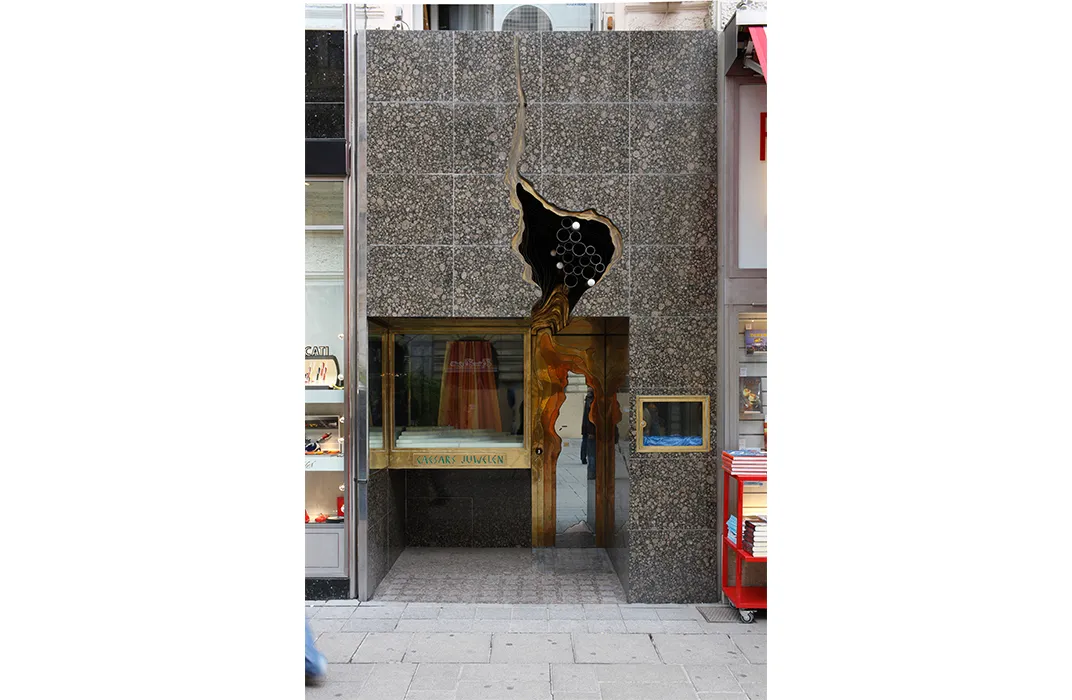

Among the sparkling storefronts, crowded kiosks, and ornate edifices of Vienna’s Kohlmarkt is a tiny shop with silver pipes bursting from a cracked granite facade leaking molten gold over its entry. The building’s jarring though well-crafted design and ostensibly decadent materials denote the wares within - high-end modern jewelry. Though it was built in 1975, the structure continues to inspire debate and discussion over the nature of its stone fragments and oozing opulence as expressions of violence or sexuality or irony or sometimes all three. And yet, despite its aggressively unique design, the Schullin jewelery shop (1975) somehow still feels firmly rooted in Vienna’s architectural traditions. This delightfully challenging little building was designed by architect Hans Hollein, a pioneer of Postmodern architecture who died last week at the age of 80.

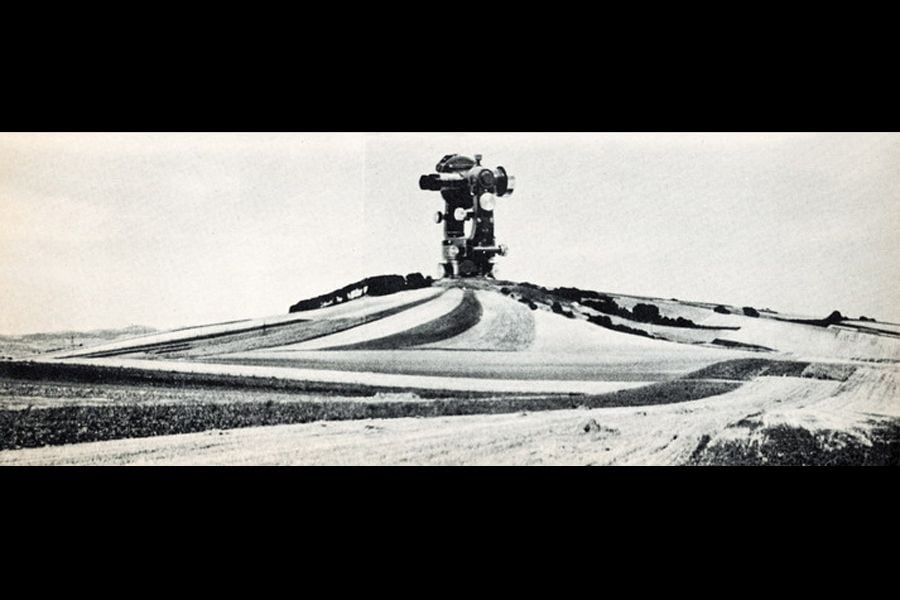

Hollein (1934-2014) was known as a designer of “witty” buildings who valued meaning over function. Born in 1934, Hollein showed an early talent for art and went on to study architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in his native Vienna before continuing his education in the United States - first at IIT in Chicago, then at U.C. Berkeley. As a student, he created satirical drawings undermining the skyscraper (and the Chicago architectural establishment) and, a little later, challenged accepted notions of form and scale with collages depicting building-sized spark plugs and city-sized aircraft carriers in desolate landscapes that call into question the nature of both form and function. During his time in the U.S., Hollein traveled extensively throughout the country in a beat-up old Chevy, famously visiting every city named "Vienna." The purple mountain majesties and fruited plains of America taught him “what it means to make man-made structures in space,” as he said in his 1985 acceptance speech for the Pritzker Prize. “A man-made environment [is] not only...a continuation and a transformation of something already existing, but the creation of something new, the artificial in a dialectic with nature.”

When he returned to the city of waltz, wine, and war in the early 1960s, his first professional commission was for the two-room Retti candle shop (1965). The storefront is clad in polished aluminum--“a true material of our century,” said Hollein-- and painstakingly detailed down to the hinges and product packaging (silver, naturally). Rather than relying on flashing signage or enormous displays, the shop only offers glimpses of its wares to perk curiosity. This modest work earned the architect wide acclaim and similar commissions followed. Though small, Hollein’s storefronts illustrate a profound interest in architectural form, engagement, and provocation. What did not interest Hollein was function. "Form does not follow function,” he wrote in 1963:

Form does not arise out of its own accord. It is the great decision of man to make a building as a cube, a pyramid,or sphere. Today for the first time in the history of mankind, at this moment when immensely developed science and perfected technology offer the means, we are building what we want, making an architecture that is not determined by technique, but that uses technique - pure, absolute architecture. Today, man is master over infinite space.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/fd/3afd0fd4-86ae-45fd-91cd-8fc4d0985421/7-hollein-aircraft-carrier.jpg)

Hollein was not advocating for purely sculptural buildings designed on a whim, he was advocating a pure, meaningful architecture. A building must of course function but its form need not be determined by that function.

As his reputation grew, so did his buildings. Hollein became known for large museums and cultural buildings, like his Haas Haus (1990), a controversial stone and glass building that seems to be stuck in a kind of stylistic transformation and yet is strangely at home in historic central Vienna. Like his earliest work, it illustrates a reverence for detailing and an irreverence for cold functionalism. Hollein’s eclectic designs embrace both modern technological capabilities and architectural history. Rather than making obscure, specific historic references, his thoughtful and often playful riffs on traditional architectural symbols and elements--the column being a particular favorite-- invite a multitude of associations and, more than anything, evoke a sense of history as a shared human experience. As the 1985 Pritzker Prize jury described him, Hollein truly was " a master of the profession who with wit and eclectic gusto draws upon the traditions of the New World as readily as upon those of the Old."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/a4/97a41310-95c9-4cfe-b902-890ef0d8aab0/1-hans-hollein-42-57035609.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/2a/7f2a0724-f5f0-49db-a8e3-9ae8bb3f482e/4-hans-hollein-wien-haas-haus.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)