Renoir’s Controversial Second Act

Late in life, the French impressionist’s career took an unexpected turn. A new exhibition showcases his radical move toward tradition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Renoir-The-Farm-at-Les-Collettes-631.jpg)

In October 1881, not long after he finished his joyous Luncheon of the Boating Party, probably his best-known work and certainly one of the most admired paintings of the past 150 years, Pierre-Auguste Renoir left Paris for Italy to fulfill a long-standing ambition. He was 40 and already acclaimed as a pioneer of Impressionism, the movement that had challenged French academic painting with its daring attempts to capture light in outdoor scenes. Represented by a leading gallery and collected by connoisseurs, he filled the enviable role of well-respected, if not yet well-paid, iconoclast.

His ambition that fall was to reach Venice, Rome, Florence and Naples and view the paintings of Raphael, Titian and other Renaissance masters. He was not disappointed. Indeed, their virtuosity awed him, and the celebrated artist returned to Paris in a state approaching shock. “I had gone as far as I could with Impressionism,” Renoir later recalled, “and I realized I could neither paint nor draw.”

The eye-opening trip was the beginning of the end of the Renoir most of us know and love. He kept painting, but in an entirely different vein—more in a studio than in the open air, less attracted to the play of light than to such enduring subjects as mythology and the female form—and within a decade Renoir entered what is called his late period. Critical opinion has been decidedly unkind.

As long ago as 1913, the American Impressionist Mary Cassatt wrote a friend that Renoir was painting abominable pictures “of enormously fat red women with very small heads.” As recently as 2007, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith bemoaned “the acres of late nudes” with their “ponderous staginess,” adding “the aspersion ‘kitsch’ has been cast their way.” Both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City have unloaded late-period Renoirs to accommodate presumably more significant works. In 1989, MOMA sold Renoir’s 1902 Reclining Nude because “it simply didn’t belong to the story of modern art that we are telling,” the curator of paintings, Kirk Varnedoe, said at the time.

“For the most part, the late work of Renoir has been written out of art history,” says Claudia Einecke, a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Renoir was seen as an interesting and important artist when he was with the Impressionists. Then he sort of lost it, becoming a reactionary and a bad painter—that was the conventional wisdom.”

If the mature Renoir came to be seen as passé, mired in nostalgia and eclipsed by Cubism and Abstract art, a new exhibition aims to give him his due. After opening this past fall at the Grand Palais in Paris, “Renoir in the 20th Century” will go to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art February 14 and the Philadelphia Museum of Art June 17. The exhibition, the first to focus on his later years, brings together about 70 of his paintings, drawings and sculptures from collections in Europe, the United States and Japan. In addition, works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Aristide Maillol and Pierre Bonnard demonstrate Renoir’s often overlooked influence on their art.

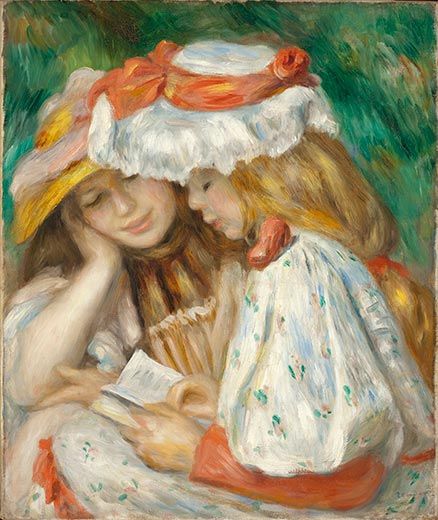

On display are odalisques and bathing nudes (including Reclining Nude, now in a private collection), Mediterranean landscapes and towns, society figures and young women combing their hair, embroidering or playing the guitar. Quite a few are modeled on famous pieces by Rubens, Titian and Velázquez or pay homage to Ingres, Delacroix, Boucher and classical Greek sculpture. “Renoir believed strongly in going to museums to learn from other artists,” says Sylvie Patry, curator of the Paris exhibit. She paraphrases Renoir: “One develops the desire to become an artist in front of paintings, not outdoors in front of beautiful landscapes.”

Curiously, though expert opinion would turn against his later works, some collectors, notably the Philadelphia inventor Albert Barnes, bought numerous canvases, and major artists championed Renoir’s efforts. “In his old age, Renoir was considered by the young, avant-garde artists as the greatest and most important modern artist, alongside Cézanne,” says Einecke.

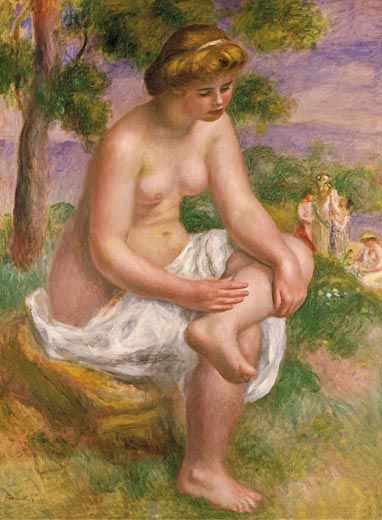

Take his 1895-1900 painting Eurydice. Based on a classical pose, the seated nude is endowed with disproportionately large hips and thighs against a diffusely painted Mediterranean landscape of pastel green and violet hues. “It was just this free interpretation of a traditional subject, this sense of liberty, that captivated Picasso,” Patry says. Eurydice was one of seven Renoir paintings and drawings Picasso collected, and, the curator adds, it was a likely inspiration for his 1921 canvas Seated Bather Drying Her Feet. (Despite attempts by Picasso’s dealer Paul Rosenberg to introduce them, the two artists never met.) Einecke remembers her art history professors dismissing Eurydice and similarly monumental Renoir nudes as “pneumatic, Michelin-tire girls.” She hopes today’s viewers will identify them with the classical mode that regarded such figures as symbols of fecundity—and see them as precursors of modern nudes done by Picasso and others.

Renoir’s late embrace of tradition also owed a great deal to settling down after he married one of his models, Aline Charigot, in 1890. Their first son, Pierre, had been born in 1885; Jean followed in 1894 and Claude in 1901. “More important than theories was, in my opinion, his change from being a bachelor to being a married man,” Jean, the film director, wrote in his affectionate 1962 memoir Renoir, My Father.

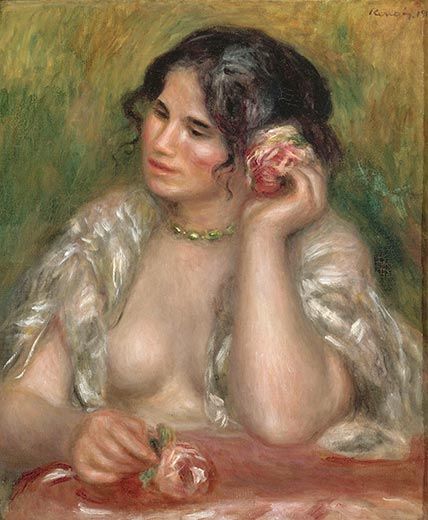

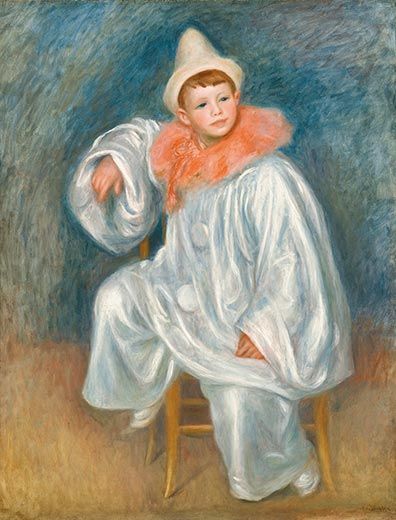

Jean and Claude Renoir were dragooned into service as models from infancy. For an 1895 painting, Gabrielle Renard—the family’s housekeeper and a frequent model—tried to entertain 1-year-old Jean as the rambunctious child played with toy animals. “Painting Gabrielle and Jean was not exactly a sinecure,” the artist quipped. Claude—who sat for no fewer than 90 works—had to be bribed with promises of an electric train set and a box of oil paints before he would wear a hated pair of tights for The Clown, his father’s salute to Jean-Antoine Watteau’s early 18th-century masterpiece Pierrot. (Years later, Picasso painted his son Paulo as Pierrot, although that work is not in the current exhibition.)

Renoir’s later portraits make little attempt to analyze the sitter’s personality. What most interested him was technique—specifically that of Rubens, whose skill with pigments he had admired. “Look at Rubens in Munich,” he told the art critic Walter Pach. “There is magnificent color, of an extraordinary richness, even though the paint is very thin.”

Renoir was also becoming less interested in representing reality. “How difficult it is to find exactly the point where a painting must stop being an imitation of nature,” he said late in his life to the painter Albert André, whom he served as a mentor. Renoir’s 1910 portrait of Madame Josse Bernheim-Jeune and her son Henry presents an expressionless mother holding her equally expressionless child. When she appealed to Auguste Rodin to persuade Renoir to make her arm look thinner, the sculptor instead advised the painter not to alter a thing. “It’s the best arm” you’ve ever done, Rodin told him. He left it alone.

Renoir, a sociable character with a sharp sense of humor, ran a lively household with his wife in the Montmartre neighborhood of Paris. Claude Monet and the poets Stéphane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud were among the dinner guests.

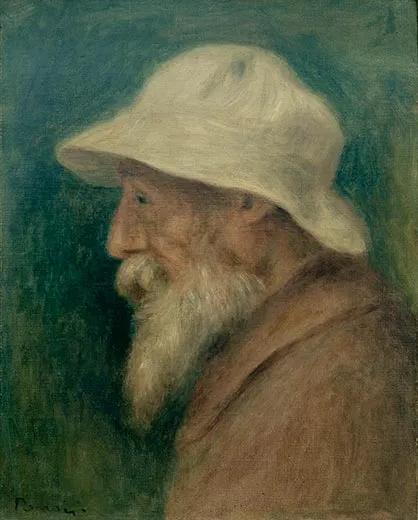

Diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis in 1897, Renoir followed his doctor’s recommendation to spend time in the warmer climate of the South of France. He bought Les Collettes farm in Cagnes-sur-Mer in 1907. Renoir’s disease would slowly cripple his hands and, ultimately, his legs, but the “threat of complete paralysis only spurred him on to renewed activity,” Jean Renoir recalled. “Even as his body was going into decline,” Matisse wrote, “his soul seemed to become stronger and to express itself with a more radiant facility.”

In 1912, when Renoir was in a wheelchair, friends enlisted a specialist from Vienna to help him walk again. After a month or so on a strengthening diet, he felt robust enough to try a few steps. The doctor lifted him to a standing position and the artist, with an enormous exertion of will, managed to wobble unsteadily around his easel. “I give up,” he said. “It takes all my willpower, and I would have none left for painting. If I have to choose between walking and painting, I’d much rather paint.”

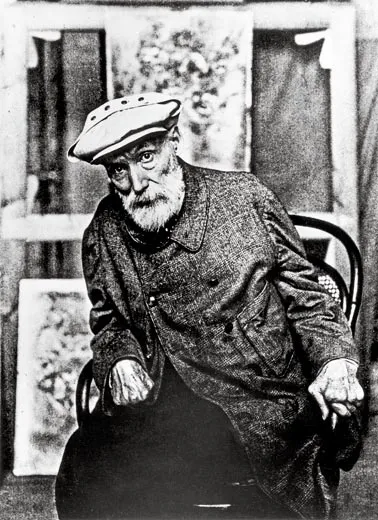

And so he did. In 1913, he announced he was approaching the goal he had set for himself after his trip to Italy 32 years before. “I’m starting to know how to paint,” the 72-year-old artist declared. “It has taken me over 50 years’ labor to get this far, and it’s not finished yet.” An extraordinary three-minute silent film clip in the exhibition captures him at work in 1915. Renoir grips his brush nearly upright in his clenched, bandaged fist and jabs at the canvas. He leans back, cocks an eye to peer at the painting, then attacks it again before putting the brush down on his palette.

It could not have been an easy time—his two elder sons had been wounded early in World War I, and his wife died that June. While millions were perishing in the trenches, in Cagnes, Renoir fashioned an Arcadia, taking refuge in timeless subjects. “His nudes and his roses declared to the men of this century, already deep in their task of destruction, the stability of the eternal balance of nature,” Jean Renoir recalled.

Auguste Renoir worked until the day he died, December 3, 1919. At the time, his studios contained more than 700 paintings (his lifetime total was around 4,000). To paint one of his final efforts, The Bathers, from 1918-19, he had had the canvas placed on vertical rollers that allowed him to stay seated while working in stages. “It’s a disturbing painting,” Patry says. The two fleshy nymphs in the foreground are “very beautiful and graceful,” she says, while the background landscape “resembles an artificial tapestry.”

Matisse anointed it as Renoir’s masterpiece, “one of the most beautiful pictures ever painted.” On one of his visits to Cagnes, he had asked his friend: Why torture yourself?

“The pain passes, Matisse,” Renoir replied, “but beauty endures.”

Longtime contributor Richard Covington writes about art, history and culture from his home near Paris.