Return of a Virtuoso

Following a debilitating stroke, the incomparable jazz pianist Oscar Peterson had to start over

He was playing “Blues Etude” when it happened. It was the first show of the night at New York City’s Blue Note club. May 1993. Oscar Peterson, then 67 and one of the greatest jazz pianists ever, found his left hand flubbing the boogie-woogie passages that climax the arrangement. He brushed the difficulty off, completed the set and went backstage with the rest of the trio.

The bassist, Ray Brown, who’d been playing with Peterson off and on for four decades, took him aside and asked if something was wrong. Peterson said it was nothing. Still, he felt dizzy, and he found his dressing room going in and out of focus. The second set was worse. He fumbled again, his left hand stiff and tingling, and now he couldn’t play the notes he’d managed just an hour before. For the first time in an international career that had begun with a surprise debut at Carnegie Hall at age 24, Peterson—known for such spectacular shows of keyboard mastery that Duke Ellington called him the “maharajah of the piano”—struggled to play.

After Peterson had returned to his home in the Toronto suburb of Mississauga, Ontario, he saw a doctor and learned that he had had a stroke, which had rendered his left side nearly immobile. It seemed that he would never perform again, and he says he soon became depressed. His ailment was all the more poignant given that his greatest asset, in addition to his astonishing dexterity, was his ability to do things with his left hand that most pianists could only dream of. Once, while performing, he reportedly leaned over and lit a cigarette for a woman in the front row with his right hand while his left scampered up and down the ivories without missing a beat.

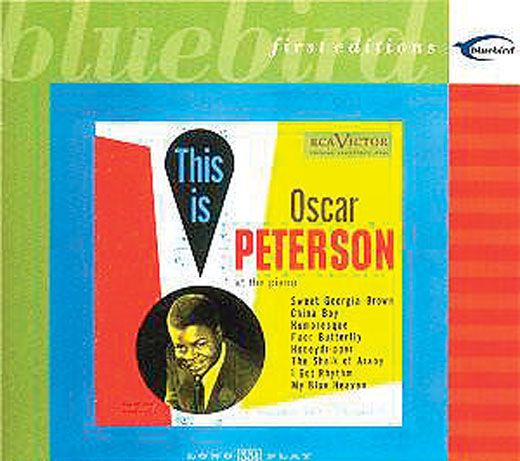

Few jazz pianists have been as widely celebrated. Anative of Montreal, Peterson received his nation’s highest cultural honor, the Order of Canada, in 1972. He was inducted into the International Academy of Jazz Hall of Fame in 1996. Though he dropped out of high school (to pursue music), he has been granted 13 honorary doctorates and, in 1991, was appointed Chancellor of York University in Toronto. He has garnered 11 Grammy nominations and seven wins, including a lifetime achievement award, and he has won more Downbeat magazine popularity polls than any other pianist.

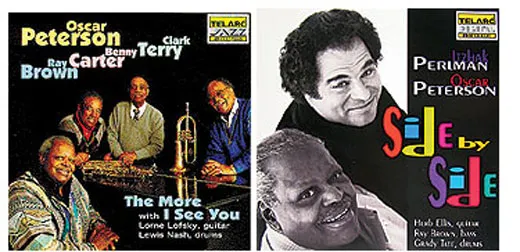

His swinging, precise, clear-as-spring-water virtuosity has been recorded on upwards of 400 albums, and the people he has played with over the decades—from Louis Armstrong to Charlie Parker to Ella Fitzgerald—are jazz immortals. Peterson “came in as a young man when the great masters were still active,” says Dan Morgenstern, director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at RutgersUniversity. “He’s a living link to what some might consider the golden age of jazz. It’s not that there aren’t many wonderful young jazz musicians around today, and the music is still very much alive. But in every art form, there are times when it reaches a peak, and that was the case with jazz at that particular time. And Oscar got in on that and he contributed to it.”

“He has the most prodigious facility of anyone I’ve ever heard in jazz,” says Gene Lees, author of a 1988 biography of Peterson, The Will to Swing. “It continued to evolve, and became more controlled and subtle—until he had his stroke.”

Born in 1925, Oscar Emmanuel Peterson was one of five children of Daniel and Olive Peterson. His father, a train porter and avid classical music fan, was from the Virgin Islands, and his mother, a homemaker who’d also worked as a maid, from the British West Indies. Oscar began playing the piano at age 5 and the trumpet the next year. His older sister Daisy, who would become a renowned piano teacher, worked with him in his early years. But it was his brother Fred, a deeply gifted pianist six years older than Oscar, who introduced him to jazz. The family was devastated when Fred died of tuberculosis at age 16. To this day Peterson insists that Fred was one of the most important influences in his musical life, and that if Fred had lived, he would have been the famous jazz pianist and Oscar would have settled for being his manager.

During their high-school years, Oscar and Daisy studied with Paul de Marky, a noted music teacher who’d apprenticed with a student of the 19th-century Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt. The link seems significant: Liszt, like Peterson, was sometimes criticized for composing music that only he could play because of his agility and sheer technical genius. Peterson, under de Marky’s tutelage, began to find his crisply swinging style.

Peterson was still a teenager when he had what he calls his first “bruising” with Art Tatum, considered by many the father of jazz piano. “I was getting perhaps a little full of myself, you know, playing for the girls at school, thinking I was quite something,” Peterson recalls. “And my father returned from one of his trips with a record. He said, ‘You think you’re so great. Why don’t you put it on?’ So I did. And of course I was just about flattened. I said, ‘That’s got to be two people playing!’ But of course it wasn’t, it was just Tatum. I swear, I didn’t play piano for two months afterward, I was so intimidated.” Only a few years later, Art Tatum himself would hear Peterson play live with one of his early trios. After the show, he buttonholed him. “It’s not your time yet,” the great man said. “It’s my time. You’re next.”

In the summer of 1949, as the story goes, Norman Granz—one of jazz’s most important producers—was in a Montreal taxicab headed for the airport when he heard Peterson’s trio playing live on the radio from the city’s Alberta Lounge. He told the cabbie to turn around and drive him to the club. Granz then invited Peterson to appear at a Carnegie Hall performance by his Jazz at the Philharmonic all-star band. Peterson accepted. As a Canadian, he didn’t have a work visa, so Granz planted him in the audience, then brought him onstage unannounced. Peterson stunned the audience playing “Tenderly” accompanied only by Ray Brown on bass. They received a standing ovation.

News of the dazzling debut traveled quickly. Peterson had “stopped” the concert “dead cold in its tracks,” Downbeat reported, adding that he “displayed a flashy right hand” and “scared some of the local modern minions by playing bop ideas in his left hand, which is distinctly not the common practice.” Peterson began touring with Granz’s band, and he soon formed his renowned trios, featuring Ray Brown on bass and first Barney Kessel and then Herb Ellis on guitar. In 1959, Peterson and Brown were joined by drummer Ed Thigpen. Which of the Peterson-led combos was the greatest is a matter of spirited musicological debate. Peterson himself says he doesn’t have a favorite group or even album, though he guesses that his 1956 At the Stratford Shakespearean Festival, with Ellis and Brown, is his bestselling recording.

Peterson, now 79, is serene, soft-spoken and wry. When he chuckles, which he frequently does, his whole body curves inward, his shoulders shake and a huge grin explodes on his face. He is elaborately courteous, in the manner of men and women of an earlier era, and full of memories. “Let me tell you a story about Dizzy Gillespie,” he says, recalling his years on the road in the 1950s. “Dizzy was wonderful. What a joy. We loved each other. Dizzy’s way of telling me he enjoyed what I did was, he’d come backstage and say, ‘You know what? You’re crazy.’ Anyway, we were traveling down South, in some of the bigoted areas. So it was two o’clock in the morning, or something like that, and we pulled up to one of those roadside diners. And I looked, and there was the famous sign: No Negroes. And the deal was, we all had duos or trios of friendship, so one of the Caucasian cats would say, ‘What do you want me to get you?’ And they’d go in, and they wouldn’t eat in there, they’d order and come back on the bus and eat with us. But Dizzy gets up and walks off the bus and goes in there. And we’re all saying, ‘Oh my God, that’s the last we’ll see of him.’ And he sits down at the counter—we could see this whole thing through the window. And the waitress goes over to him. And she says to him, ‘I’m sorry, sir, but we don’t serve Negroes in here.’ And Dizzy says, ‘I don’t blame you, I don’t eat ’em. I’ll have a steak.’ That was Dizzy exactly. And do you know what? He got served.”

In 1965, Peterson recorded Oscar Peterson Sings Nat King Cole. “That album was made under duress,” Peterson recalls. “Norman Granz talked me into doing it. And I’ll tell you a story about that. Nat Cole came in to hear me in New York one night. And he came up and said to me, ‘Look, I’ll make you a bargain. I won’t play the piano if you won’t sing.’ ” Peterson cracks himself up. “I love Nat so much. I learned so much from him.”

Over the years, the criticism that would dog Peterson more than any other was that his virtuosity, the source of his greatness, masked a lack of true feeling. Areviewer in the French magazine Le Jazz Hot wrote in 1969 that Peterson “has all the requisites of one of the great jazz musicians. . . . Save that élan, that poesy, . . . that profound sense of the blues, all that is difficult to define but makes the grandeur of an Armstrong, a Tatum, a Bud Powell, a Parker, a Coltrane or a Cecil Taylor.”

Peterson fans and many fellow musicians insist it’s a bad rap. “Oscar plays so cleanly that nobody can believe he’s a jazz guy,” says jazz pianist Jon Weber. “Maybe the expectation is that jazz is going to be sloppy or clumsy, but it’s not. There are going to be times when a down-and-dirty blues is exactly what you’ve gotta do, like this—” he pauses and lays down a riff on his piano that heats up the phone lines—“and it might sound sloppy to the uninitiated. But Oscar plays with such flawless technique that it makes people think, ‘Well, it’s too clean to be jazz.’ What has a guy got to do to convince them that he’s playing with emotion? From the first four bars, I hear his heart and soul in every note.”

Morgenstern compares the criticism of Peterson’s work to the complaint that Mozart’s music had “too many notes.” “Just virtuoso displays of technical facility are relatively shallow and meaningless,” Morgenstern says. “But with Oscar, it’s not like that. He obviously has such a great command of the instrument that he can do almost anything. The thing about Oscar is that he enjoys that so much, he has so much fun doing it. So sure, he’s all over the keyboard, but there’s such a zest for it, such a joie de vivre, that it’s a joy to partake of that.”

Herb Ellis once said of Peterson, “I’ve never played with anybody who had more depth and more emotion and feeling in his playing. He can play so hot and so deep and earthy that it just shakes you when you’re playing with him. Ray and I have come off the stand just shook up. I mean, he is heavy.”

In an interview, Downbeat’s contributing editor, John McDonough, once asked Peterson about a critic’s complaint that he was a “cold machine.” “

So sue me,” Peterson said. “I am the kind of piano player I am. I want to address the keyboard in a certain way. I want to be able to do anything my mind tells me to do.”

Summer 1993. Peterson sits at the kitchen table in his house in Mississauga. His daughter Celine, then a toddler, sits across from him, shooting toy trucks at him across the table. He catches them with his right hand. Celine says, “No, Daddy! With the other hand! Use your other hand!”

Peterson says it was the darkest time of his life. The frustration of daily physical therapy wore on him, and when he sat down at the piano, that full sound, his sound, no longer filled the room. His left hand lay mostly limp on the keyboard.

Not long after he was stricken, the bassist Dave Young called Peterson and announced that he was coming over with his instrument. Peterson said, “Dave, I can’t play.” “

What do you mean, you can’t play?” “

I can’t play no more.”

“You’re gonna play. I’m coming over.”

Young came over, and Peterson remembers, “he called all these tunes that required both hands. He said, ‘See, there’s nothing wrong with you. You should play more often.’ ”

After about 14 months of intensive physical therapy and practice, one of the world’s greatest jazz pianists made his comeback debut at his daughter’s elementary school. Soon he moved on to local clubs. “The piano field’s very competitive,” Peterson says. “And at different times, players would come to hear me, and that little gnome would tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘So-and-so’s out there. Are you going to miss tonight?’ ”

Benny Green, a pianist influenced by Peterson’s work, “wouldn’t accept me walking away. He said, ‘If you’ve got one finger, you’ve got something to say, so don’t even go that way. We can’t accept that loss.’ I just figured, take me as I am. If this is what I’m going to be, then this is what I’m going to be. If I couldn’t express myself with whatever is left—and I’m not saying my playing is what it used to be— but if I can’t express myself, I wouldn’t be up there. If I can’t speak to you in a discernible voice, I wouldn’t bother having the conversation.”

“Of course, Norman [Granz] was alive at that time, and he’d call me up every day. He’d say, ‘How’re you doing?’ And I’d say, ‘Aw, I don’t know.’ And he’d say, ‘Don’t give me that sob story. I don’t want to hear it. When are you going to play?’ ” Granz, Peterson’s manager and longtime friend, wanted to book him, and Oscar finally agreed. “I distinctly remember standing in the wings at a concert in Vienna,” Peterson says. “And I had that last wave of doubt.” Niels Pederson, his bassist, asked how he was doing. Peterson said,

“Niels, I don’t know if I can come up with this one.”

“ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘now’s a hell of a time to back out. You better play, because I’m going to be running up one side of you and down the other if you don’t.’ And I managed to get through the concert. We went out to eat afterward, and I was sitting in the restaurant. And I felt Norman’s arms around me, and he said, ‘I’ve never been more proud of you than I am tonight.’ ”

Peterson slowly makes his way into the sunroom at the back of his house. The room is alive with afternoon light and crowded with plants and flowers. Elsewhere in the house are Peterson’s wife of 18 years, Kelly, and their 13-year-old daughter, Celine. He also has six children from two of his other three marriages, and he relishes his role as father and grandfather. His family, he says, is the reason he keeps playing— that, he adds, and “the man upstairs.”

He continues to tour and compose, he says, because he loves the piano. “It’s such a vast instrument I play. I approach it with a very humble attitude—you know, are we going to be able to talk today? I believe that this music is a very important part of our worldly culture. I’ve always believed that. And because of the improvisational nature of jazz, and the emotional aspect of it, I believe it’s one of the most truthful voices in the arts. I don’t see myself as a legend. I think of myself as a player that has emotional moments, musically speaking, that I want to bring forward. And jazz gives me the opportunity to do that.”

Downbeat’s McDonough recalls seeing Peterson perform after the stroke: “I thought he was performing wonderfully. And it wasn’t until the second or third concert that I happened to see that he was not using his left hand. But his right hand was working so hard, and giving so much, it just didn’t occur to me that I was listening essentially to a one-handed pianist. With all the accolades that came to Peterson during his prime years, it seemed to me that even greater accolades should be afforded him, because he could do what he could do with one hand. He had skill to burn. He lost half his resources, and it’s astonishing what he can still produce.”

These days Peterson spends most of his musical time composing, a process that was not hindered by his stroke and that is aided by his love of gadgets. He has a studio in his home, and often starts out “doodling” on keyboards hooked up to computers. “Most of my writing is spontaneous,” he says. “In jazz, it comes directly from your inner feelings at that exact moment in time,” he says. “I don’t necessarily start out with anything. Most of it is built on one thing—emotion. And I say that not being maudlin. Inwardly, I’m thinking of something in particular, something I like or something that’s getting to me. And at some point it comes out musically.”

Peterson’s talents as a composer, which have been largely overshadowed by his strengths as a performer, began with a dare. “My bassist Niels Pederson said, ‘Why don’t you write something?’ I said, ‘Now?’ He said, ‘Yeah! You’re supposed to be so big and bad. Go ahead.’ I figured he was getting a little uppity so I’d face this challenge. So I wrote ‘The Love Ballad’ for my wife.” Likewise for Canadiana Suite, which he recorded in 1964. “That was started on a bet,” he says, chuckling. “I had been messing with Ray Brown”—Peterson is a notorious practical joker, and Brown was one of his favorite victims— “I would go steal his cuff links and what have you. And he said, ‘Why don’t you make good use of your time instead of messing with me? Why don’t you go write something?’ I said, ‘What do you want me to write?’ I was in a very cavalier mood. He said, ‘You know, Duke [Ellington] has written a “this suite” and a “that suite,” why don’t you go write a suite?’ I said, ‘OK, I’ll be back.’ ” Peterson chuckles. “The first piece I wrote was ‘Wheatland,’ and I started on ‘Blues of the Prairies.’ And I called Ray over. He said, ‘Well, when are you going to finish it?’ I said, ‘Ray, we gotta go to work! I would, but’—and he said, ‘Well, finish the so-and-so thing. Two pieces is not a suite. Canada’s a big, big country. What’re you gonna do about that?’ ” Asweeping musical meditation on the grandeur of the Canadian landscape, Canadiana was hailed by one critic as a “musical journey.”

Summer 2004. Tonight Peterson is decked out in a bluespangled tux with satin lapels and a bow tie, cuff links the size of quarters, and blue suede shoes. The audience is on its feet the moment he rounds the corner and heads slowly, painfully, onto the stage at the legendary Birdland in New York City. Peterson nods to the cheering crowd. Gripping the Boesendorfer piano as he goes, he grins and finally settles himself before the keyboard. With bass, drums and guitar behind him, he glides into “Love Ballad.” The room seems to swell with a sigh of pleasure. Here in New York, where he emerged as an entirely new force in jazz half a century before, Peterson sweeps through a set of ballads and swing, Dixieland and blues, bringing the crowd to its feet as he closes with “Sweet Georgia Brown.” Backstage between sets, Peterson eats ice cream. “Whew!” he says. “Well, it got very heavy. I had a ball.”

As he makes his way onstage for his second set, Peterson grins and nods to the audience, which stands and cheers the second he rounds the corner. He settles himself onto the piano bench, shoots a glance at Niels Pederson, and the music rolls into the room like a wave: the slow, steady lick of Alvin Queen’s brush on the snare, the resonant voice of the bass thrumming up from the depths, the easy, rhythmic tide of Ulf Wakenius’ guitar, and then, like raindrops on water, the delicate sound of Oscar’s elegant right hand on the keys. Later he is asked what he played in the second set. He chuckles, saying, “Anything I could remember.”