Return to the Marsh

The effort to restore the Marsh Arabs’ traditional way of life in southern Iraqvirtually eradicated by Saddam Hussein faces new threats

The British Royal Air Force helicopter sweeps low over a sea of marsh grass, then banks sharply to the left, hurling me off my seat and onto the chopper’s rough metal floor. Fifty feet below, pools of silver water speckled with rust-colored flora and lush reed islands in cookie-cutter shapes extend in every direction. Women swathed in black veils and black robes called abayas punt long boats past water buffalo lolling in the mud. Sparkles of light dance off a lagoon, and snowy herons glide over the wetlands.

I'm traveling with a unit of British soldiers deep into Al Hammar Marsh, a 1,100-square-mile freshwater sea located between the southern Iraqi cities of An Nasiriyah and Basra, the country's second largest after Baghdad. Saddam Hussein's engineers and soldiers turned it into a desert after the Persian Gulf war of 1991, but during the past three years—thanks to a dismantling of dikes and dams built on Saddam's orders in the early 1990s—the marshlands have been partially rejuvenated. Now this fragile success is facing new onslaughts—from economic deprivations to deadly clashes among rival Shiite militias.

The Merlin chopper touches down in a muddy field beside a cluster of mud-brick and reed houses. A young Romanian military officer with a white balaclava around his head rushes up to greet us. He's part of a "force protection" group dispatched from An Nasiriyah in armored personnel carriers to make sure that this British reconnaissance team—scouting villages for an upcoming World Environment Day media tour—gets a warm reception from the local population. As we climb out of the muck and onto a dirt road, the Merlin flies off to a nearby military base, leaving us in a silence I've never before experienced in Iraq. A few moments later, two dozen Iraqi men and boys from a nearby village, all dressed in dishdashas—gray traditional robes—crowd around us. The first words out of their mouths are requests for mai, water. As Kelly Goodall, the British Army's interpreter, hands out bottles of water, a young man shows me a rash on his neck and asks if I have anything for it. "It comes from drinking the water in the marshes," he tells me. "It isn't clean."

The villagers tell us they haven't seen a helicopter since the spring of 1991. That was when Saddam sent his gunships into the wetlands to hunt down Shiite rebels and to strafe and bomb the Marsh Arabs who had supported them. "We came back from An Nasiriyah and Basra after the fall of Saddam, because people said it was better to go back to the marshes," the village chief, Khathem Hashim Habib, says now. A hollow-cheeked chain smoker, Habib claims to be only 31 years old, but he looks 50, at least. Three years after the village reconstituted itself, he says, there are still no paved roads, no electricity, no schools and no medicine. Mosquitoes swarm at night, and nobody has come to spray with insecticide. The nearest market for selling fish and water-buffalo cheese, the economic mainstays, is an hour away by truck; during the rainy months, the Euphrates River rises, washing out the road, swamping the village and marooning everyone in the muck.

"We want help from the government," Habib says, leading us down the road to his home—four sheets of tightly woven reeds stretched over a metal frame. "The officials in Basra and Nasiriyah know that we're here, but help isn't coming," he tells a British officer.

"We're here to see exactly what needs to be done," the officer, fidgeting, assures the chief. "We'll work with the Basra provincial council, and we’ll make some improvements."

Habib doesn't appear convinced. "We haven't seen anything yet," he calls after the troops as they head down the road to await the Merlin's return. "So far it's been just words." As the British hustle me along, I ask Habib if he would prefer going back to live in the cities. He shakes his head no, and his fellow villagers join in. "Life is difficult now," he tells me, "but at least we have our marshes back."

A complex ecosystem created by the annual flooding of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, Iraq's marshes have sustained human civilization for more than 5,000 years. Some of the earliest settlements of Mesopotamia—"the land between the rivers"—were built on floating reed islands in these very wetlands. This was one of the first places where human beings developed agriculture, invented writing and worshiped a pantheon of deities. In more recent times, the remoteness of the region, the near-absence of roads, the difficult terrain and the indifference of Baghdad's governing authorities insulated the area from the political and military upheavals that buffeted much of the Arab world. In his 1964 classic, The Marsh Arabs, British travel writer Wilfred Thesiger described a timeless environment of "stars reflected in dark water, the croaking of frogs, canoes coming home at evening, peace and continuity, the stillness of a world that never knew an engine."

Saddam Hussein changed all that. Construction projects and oilfield development in the 1980s drained much of the wetlands; the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88) forced people to flee from border areas to escape mortar and artillery attacks. By 1990 the population had fallen from 400,000 to 250,000. Then came the gulf war. After the U.S.-led coalition routed Saddam's army in March 1991, President George H.W. Bush encouraged the Kurds and Shiites to rebel against Saddam, then, when they did so, declined to support them. Saddam reconstituted his revolutionary guard, sent in helicopter gunships and slaughtered tens of thousands. Shiite rebels fled to the marshes, where they were pursued by tanks and helicopters. Iraqi ground troops torched villages, set fire to reed beds and killed livestock, destroying most of the region's economic viability.

In 1992, Saddam began the most insidious phase of his anti-Shiite pogroms. Workers from Fallujah, Tikrit and other Baathist strongholds were transported to the south to construct canals, dams and dikes that blocked the flow of rivers into the marshes. As the wetlands dried up, an estimated 140,000 Marsh Arabs were driven from their homes and forced to resettle in squalid camps. In 1995, the United Nations cited "indisputable evidence of widespread destruction and human suffering," while a report by the United Nations Environmental Program in the late 1990s declared that 90 percent of the marshes had been lost in "one of the world's greatest environmental disasters."

After the overthrow of Saddam in April 2003, local people began breaching the dikes and dams and blocking the canals that had drained the wetlands. Ole Stokholm Jepsen, a Danish agronomist and senior adviser to the Iraqi Minister of Agriculture, says that "recovery has happened far faster than we ever imagined"; at least half of the roughly 4,700 square miles of wetland has been reflooded. But that's not the end of the story. Fed by the annual snowmelt in the mountains of Anatolia, Turkey, the marshes were once among the world's most biologically diverse, supporting hundreds of varieties of fish, birds, mammals and plant life, including the ubiquitous Phragmites australis, or ordinary marsh reed, which locals use to make everything from houses to fishing nets. But Saddam's depredations, combined with ongoing dam projects in Turkey, Syria and northern Iraq, have interfered with the natural "pulsing" of floodwaters, complicating restorative processes. "Nature is healing itself," said Azzam Alwash, a Marsh Arab who immigrated to the United States, returned to Iraq in 2003 and runs the environmental group Nature Iraq, based in Baghdad. "But many forces are still working against it."

I first visited the marshes on a clear February day in 2004. From Baghdad I followed a stretch of the mighty, 1,100-mile-long Tigris River southeast to the predominantly Shiite town of Al Kut, near the Iran border. At Al Kut, I headed southwest away from the Tigris through the desert to An Nasiriyah, which straddles the banks of the 1,730-mile-long Euphrates. The ziggurat of Ur, a massive stepped pyramid erected by a Sumerian king in the 21st century b.c., lies just a few miles west of An Nasiriyah. To the east, the Euphrates enters the Al Hammar Marsh, reappearing north of Basra, where it joins the Tigris. The Bible suggests that Adam and Eve's Garden of Eden lay at the confluence of the two rivers. Today the spot is marked by a dusty asphalt park, a shrine to Abraham, and a few scraggly date palm trees.

I was joined in An Nasiriyah, a destitute city of 360,000 and the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the ongoing war, by a former Shiite guerrilla who uses the name Abu Mohammed. A handsome, broad-shouldered man with a gray-flecked beard, Abu Mohammed fled An Nasiriyah in 1991 and spent five years hiding in the marshes following the rebels' defeat. In mid-1996, he and a small cell of Shiite conspirators plotted the assassination of Uday Hussein, Saddam's psychopathic son. Four of Abu Mohammed's comrades gunned down Uday—and left him paralyzed—on a Baghdad street that December. Saddam's Republican Guards pursued the conspirators through the marshes, burning rushes and reeds, knocking down eucalyptus forests and bulldozing and torching the huts of any local villagers who provided shelter to the rebels. Abu Mohammed and his comrades fled across the border to Iran. They didn't begin filtering back to Iraq until U.S. forces routed Saddam in April 2003.

After half an hour's drive east out of An Nasiriyah, through a bleak, pancake-flat landscape of stagnant water, seas of mud, dull-brown cinder-block houses, and minarets, we came to Gurmat Bani Saeed, a ramshackle village at the edge of the marshes. It is here that the Euphrates River divides into the Al Hammar Marsh, and it was here that Saddam Hussein carried out his ambition to destroy Marsh Arab life. His 100-mile-long canal, called the Mother of All Battles River, cut off the Euphrates and deprived the marshes of their prime water source. After its completion in 1993, "not a single drop of water was allowed to go into Al Hammar," Azzam Alwash would later tell me. "The entire marsh became a wasteland."

In April 2003, Ali Shaheen, director of An Nasiriyah's irrigation department since the late 1990s, cranked open three metal gates and dismantled an earthen dike that diverted the Euphrates into the canal. Water washed across the arid flats, reflooding dozens of square miles in a few days. Almost simultaneously, local people 15 miles north of Basra tore down dikes along a canal at the south end of the marsh, allowing water to flow from the Shatt-al-Arab, the waterway at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. In all, more than 100 dams and embankments were destroyed in those first exhilarating days when everything seemed possible.

Abu Mohammed led me down narrow causeways that ran past newly formed seas dappled by mud flats and clumps of golden reeds. Choruses of frogs warbled from lily pad clusters. "This used to be a dry part of the marsh," he said. "We used to walk over it, but you see it is filling up." The returning Marsh Arabs had even formed a rudimentary security force: rugged-looking men armed with Kalashnikovs, who were both protecting visitors and trying to enforce fatwas issued by the Grand Ayatollah Ali Al Sistani, the preeminent religious leader of Iraq's Shiite Muslims. With coalition troops stretched thin and no effective police or judicial system in place, the local guardsmen served as the only law and order in the region. One patrol was combing the marshes for fishermen who violated Sistani’s prohibition against "electroshock fishing": using cables connected to a car battery to electrocute all the fish in a three-foot radius. The prohibited method was threatening the marsh's resuscitation just as it was getting under way.

When I returned to the marshes in May 2006, southern Iraq, like the rest of the country, had become a far more dangerous place. An epidemic of kidnappings and ambush killings of Westerners had made travel on Iraq’s roads highly risky. When I first announced that I hoped to visit the marshes without military protection, as I had done in February 2004, both Iraqis and coalition soldiers looked at me as if I were crazy. "All it takes is one wrong person to find out that an American is staying unprotected in the marshes," one Shiite friend told me. "And you may not come out."

So I hooked up with the 51 Squadron RAF Regiment, a parachute- and infantry-trained unit that provides security for Basra's International Airport. When I arrived at their headquarters at nine o'clock on a May morning, the temperature was already pushing 100 degrees, and two dozen soldiers—wearing shoulder patches displaying a black panther, a Saracen sword and the regimental motto, "Swift to Defend"—were working up a sweat packing their armored Land Rovers with bottled water. Flight Lt. Nick Beazly, the patrol commander, told me that attacks on the British in Basra had increased the past six months to "once or twice a week, sometimes with a volley of five rockets." Just the evening before, Jaish al-Mahdi militiamen loyal to renegade Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, had blown up an armored Land Rover with a wire-detonated artillery round, killing two British soldiers on a bridge on Basra's northern outskirts. Kelly Goodall, the British interpreter who had joined me several days earlier on the helicopter trip to the marshes, had been called away at the last minute to deal with the attack. Her absence left the team with nobody to translate for them—or me. Every last local translator, I was told, had resigned during the past two months after getting death threats from Jaish al-Mahdi.

We stopped beside a wire-mesh fence that marks the end of the airfield and the beginning of hostile territory. Grim-faced soldiers locked and loaded their weapons. At a bridge over the Shatt al-Basra Canal, the troops dismounted and checked the span and surrounding area for booby traps. Then, just over a rise, the marshes began. Long boats lay moored in the shallows, and water buffalo stood half hidden in the reeds. As we bounced down a dirt road that bordered the vast green sea, the soldiers relaxed; some removed their helmets and put on cooler light blue berets, as they are sometimes allowed to do in relatively safe areas. After a 30-minute drive, we reached Al Huwitha, a collection of mud-and-concrete-block houses strung along the road; a few homes had satellite dishes on their corrugated tin roofs. Children poured out of the houses, greeting us with thumbs up and cries of "OK." (The British battle for hearts and minds has actually paid off in Al Huwitha: after the reflooding, troops dumped thousands of tons of earth on waterlogged terrain to raise land levels for housing construction in certain spots, then improved electrification and water purification. "We're happy with the British," said one local man. "We have no problems with them, hamdilullah [thanks to God].")

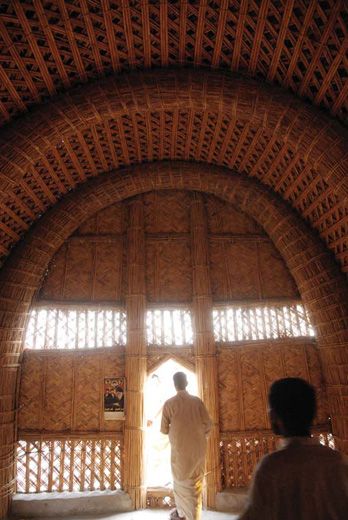

In the center of Al Huwitha rose a large mudheef, a 30-foot-high communal meetinghouse made entirely of reeds, with an elegant curving roof. Some local men invited me inside—I was able to talk to them in rudimentary Arabic—and I gazed at the interior, which consisted of a series of a dozen evenly spaced, cathedral-like arches, tightly woven from reeds, supporting a curved roof. Oriental carpets blanketed the floor, and at the far end, glowing in the soft natural light that seeped in through a doorway, I could make out richly colorful portraits of Imam Ali, son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad, and his son, Imam Hussein, the two martyred saints of Shiite Islam. "We built the mudheef in 2003, following the old style," one of the men told me. "If you go back 4,000 years, you will find exactly the same design."

Al Huwitha's biggest problem stems from an unresolved tribal feud that goes back 15 years. The people of the village belong to a tribe that sheltered and fed the Shiite rebels just after the gulf war. In the summer of 1991, some 2,500 members of a rival tribe from Basra and wetlands to the north showed Saddam's Republican Guards where the Al Huwitha men were hiding. The Guards killed many of them, a British intelligence officer told me, and there’s been bad blood between the two groups ever since. "Al Huwitha's men can't even move down the road toward Basra for fear of the enemy group," the officer went on. "Their women and children are allowed to pass to sell fish, buffalo cheese, and milk in Basra markets. But the men have been stuck in their village for years." In 2005, a furious battle between the two tribes erupted over a love affair—"a Romeo and Juliet story," the officer added. The fighting lasted for days, with both sides firing rocket-propelled grenades, mortars and heavy machine guns at each other. The officer asked the sheik of Al Huwitha "if there was any chance of a truce, and he said, 'This truce will happen only when one side or the other side is dead.'"

The violence among Shiite groups in and around Basra has escalated sharply in recent months. In June Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki declared a state of emergency and sent several thousand troops to the area to restore order. In August supporters of an assassinated Shiite tribal leader lobbed mortar rounds at bridges and laid siege to the governor's office to demand that he arrest their leader's killers.

Driving back toward Basra, we passed a settlement being built on a patch of wasteland within sight of the airport's control tower. The settlers, Marsh Arabs all, had abandoned their wetlands homes two months earlier and were constructing squat, ugly houses out of concrete blocks and corrugated tin. According to my British escorts, the part of the marshes where they had lived is owned by sayeds, descendants of the prophet Muhammad, who forbade them from building "permanent structures," only traditional reed houses. This was unacceptable, and several hundred Marsh Arabs had picked up and moved to this bone-dry patch. It is a sign of the times: despite reconstruction of a few mudheefs, and some Marsh Arabs who say they would like to return to the old ways, the halcyon portrait of Marsh Arab life drawn by Wilfred Thesiger half a century ago has probably disappeared forever. The British officer told me he had asked the settlers why they didn't want to live in reed huts and live off the land. "They all say they don't want it," the officer said. "They want sophistication. They want to join the world." Ole Stokholm Jepsen, the Danish agronomist advising the Iraqis, agreed. "We will have to accept that the Marsh Arabs want to live with modern facilities and do business. This is the reality."

Another reality is that the marshes will almost certainly never recover completely. In earlier times, the Tigris and Euphrates, overflowing with snowmelt from the Turkish mountains, spilled over their banks with seasonal regularity. The floods flushed out the brackish water and rejuvenated the environment. "The timing of the flooding is vital to the health of the marshes," says Azzam Alwash. "You need fresh water flowing in when the fishes are spawning, the birds are migrating, the reeds are coming out of their winter dormancy. It creates a symphony of biodiversity."

But these days, the symphony has dwindled to a few discordant notes. Over the past two decades, Turkey has constructed 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric power plants on the Euphrates and Tigris and their tributaries, siphoning off water before it ever crosses Iraq's northern border. Before 1990, Iraq got more than three trillion cubic feet of water a year; today it's less than two trillion. The Central and Hammar marshes, which are dependent upon the heavily dammed Euphrates, get only 350 billion cubic feet—down from 1.4 trillion a generation ago. As a result, only 9 percent of Al Hammar and 18 percent of the Central Marsh have been replenished, says Samira Abed, secretary general of the Center for Restoration of the Iraqi Marshes, a division of Iraq's Water Resources Ministry. "They are both still in a very poor state." (The Al Hawizeh Marsh, which extends to Iran and receives its water from the Tigris, has recovered 90 percent of its pre-1980 area.)

Linda Allen, an American who serves as senior consultant to the Iraqi Ministry of Water, told me that getting more water from Turkey is essential, but despite "keen interest among Iraqis" to strike a deal, "there is no formal agreement about the allocation and use of the Tigris and Euphrates." Iraq and Turkey stopped meeting in 1992. They met once earlier this year, but meanwhile the Turks are building more upstream dams.

Azzam Alwash believes that intransigence on both sides dooms any negotiations. His group, Nature Iraq, is promoting an alternative that, he claims, could restore the marshes to something like full health with three billion cubic meters of additional water per year. The group calls for constructing movable gates on Euphrates and Tigris tributaries to create an "artificial pulse" of floodwater. In late winter, when Iraq's reservoirs are allowed to flow into the Persian Gulf in anticipation of the annual snowmelt, gates at the far end of the Central and Al Hammar marshes would slam shut, trapping the water and rejuvenating a wide area. After two months, the gates would reopen. Though the plan would not exactly replicate the natural ebb and flow of floodwaters of a generation ago, "if we manage it well," Alwash says, "we can recover 75 percent of the marshes." He says that the Iraqi government will need between $75 million and $100 million to build the gates. "We can do this," he adds. "Bringing back the marshes is hugely symbolic, and the Iraqis recognize that."

For the moment, however, Alwash and other marshlands environmentalists are setting their sights lower. In the past three years, Nature Iraq has spent $12 million in Italian and Canadian government funds to monitor salinity levels of marsh water and to compare "robust recovery" areas with those in which fish and vegetation have not thrived. Jepsen, working with the Iraqi Agriculture Ministry, is running fisheries, water-buffalo breeding programs and water-purification schemes: both agriculture and water quality, he says, have improved since Saddam fell. In addition, he says, the "maximum temperatures during the summer have been significantly reduced" across Basra Province.

Sitting in his office in Saddam's former Basra palace, Jepsen recalls his first year—2003—in Iraq wistfully. In those days, he says, he could climb into his four-by-four and venture deep into the marshes with only an interpreter, observing the recovery without fear. "During the last six months, the work has grown extremely difficult," he says. "I travel only with the military or a personal security detail. I am not here to run a risk on my life." He says discontent among the Marsh Arabs is also rising: "In the days after reflooding, they were so happy. But that euphoria has worn off. They are demanding improvements in their lives; the government will have to meet that challenge."

In the marshlands, as in so much of this tortured, violent country, liberation proved to be the easy part.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)