This is the story of a singer who grew up among white country folk outside Greensboro, North Carolina, cooing along to Lawrence Welk and giggling to “Hee Haw,” the cornhusk-flavored variety show with an all-white cast. Graced with an agile soprano voice, she studied opera at Oberlin College, then returned to her home state, took up contra dancing and Scottish song, studied Gaelic, and learned to play banjo and bluegrass fiddle. She married (and later separated from) an Irishman and is raising a daughter, Aoife, and a son, Caoimhín, in Limerick. Among her regular numbers is a cover of the 1962 weepie “She’s Got You” by Patsy Cline, the country music matriarch and onetime star of the Grand Ole Opry.

This is also the story of a singer who grew up on the black side of Greensboro, reading the activist poet Audre Lorde and harmonizing to R&B bands like the Manhattans. She started the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a black string band that won a Grammy for its album Genuine Negro Jig. She excavates forgotten songs by anonymous field hands and pays tribute to the pioneers of gospel. One of her regular numbers is “At the Purchaser’s Option,” a haunting ballad written in the voice of a mother waiting with her baby on the slave auction block. She often begins a set with a declaration by the poet Mari Evans: “I am a black woman.”

And because this is America, those two singers are the same person: Rhiannon Giddens, an electrifying artist who brings alive the memories of forgotten predecessors, white and black. She was born in 1977, in a South that was going through spasms of racial transformation. Her parents—a white father, David Giddens, and a black mother, Deborah Jam- ieson, both from Greensboro and both music enthusiasts with wide-ranging tastes—married ten years after the lunch-counter sit-ins of 1960 and just three years after the Supreme Court decided Loving v. Virginia, making interracial marriage legal in every state. When her parents split, Rhiannon and her sister, Lalenja, shuttled back and forth between the two halves of their clan, who lived 20 miles apart in segregated Guilford County. The girls found that those worlds were not, after all, so distant. One grandmother fried okra in flour batter while the other used cornmeal. One parent fired up the record player to accompany a barbecue, the other broke out the guitar. But both families were country people who spoke with similar accents and shared a deep faith in education—and music.

Today, Giddens, 42, is both a product and a champion of America’s hybrid culture, a performing historian who explores the tangled paths of influence through which Highland fiddlers, West African griots, enslaved banjo players and white entertainers all shaped each other’s music. She belongs to a cohort of scholar-musicians who have waded into the prehistory of African-American music, the period before it was commercialized by publishers, broadcasters, dance bands and record producers. “Rhiannon uses her platform as a clearinghouse of source material, so the history can be known,” says Greg Adams, an archivist and ethnomusicologist at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. “Her role is to say: Here’s the scholarly output, here are the primary sources, and here’s my synthesis and expression of all that knowledge. She shows how the historical realities connect to what’s happening today.”

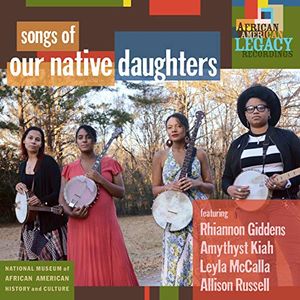

Realizing those noble intentions depends on Giddens’ one essential tool: her gift as a performer. With a galvanizing voice and magnetic stage presence, she sings traditional songs, supplies new words for old tunes, composes fresh melodies for old lyrics, and writes songs that sound fresh yet also as if they have existed for centuries. Her latest recording, Songs of Our Native Daughters, just released on Smithsonian Folkways, uses ravishing music to draw listeners through some of the darkest passages in America’s history, and out to the other side.

* * *

One summer afternoon, I find Giddens in a Victorian house in Greensboro she has rented for the weekend of the North Carolina Folk Festival. A handful of people cluster around a dining room table, rehearsing for that night’s show. Giddens’ sister, Lalenja Harrington, runs a program for students with intellectual disabilities at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, but she’s signed on for a temporary stint as vocalist and tour manager. She looks up from copying out the set list long enough to suggest a change to an arrangement, then checks her phone for festival updates. She’s the designated worrier.

The tap dancer Robyn Watson quietly beats out rhythms with her bare feet under the table. She’s one of Giddens’ relatively recent friends; they laugh ruefully at the memory of grueling sessions when Watson trained Giddens for her abortive Broadway debut in Shuffle Along. (The show closed in 2016, before Giddens could step in for Audra McDonald, the show’s pregnant star.) Jason Sypher, in town from New York, perches on a stool and hugs his double bass. He says little, but his fingers slip into sync as soon as Giddens starts humming.

The musicians improvise intros and try out tempos. “They know my vibe,” Giddens shrugs. “I have a flavor: kind of modal-y, kind of Renaissance-y, kind of eastern-y, trance-y and rhythmic. They get it.”

During rehearsal, just as she’s sliding into “Summertime,” the voluptuous aria in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, Giddens receives a text message asking if she’d like to star in a staged production of the opera. “Cool,” she says, then falls right back into the song.

Bass and piano have started at a tempo so languid you can practically hear the cicadas, and she joins in with a throaty flamenco rasp, which elicits giggles all around. She grins and continues, drawing out the “n” in “cotton” into a nasal hum. It’s almost magical but not quite there, and she loses her way in the words. She nods: It’s OK; everything will come together a couple of hours from now. (It does.) At one point, the pianist, Francesco Turrisi, also Giddens’ boyfriend, improvises a Bach-like two-part invention on the house’s out-of-tune upright. “Did you just make that up?” Giddens asks, and he smiles.

A clutch of folk music scholars shows up. Giddens assigns them each a berth and promises some good post-concert hangout time. This impromptu conclave of musicians and researchers, sharing a couple of bathrooms and a refrigerator stocked with beer, is the kind of extravagance she has been able to indulge in since the MacArthur Foundation awarded her a $625,000 “genius” grant in 2017. (The prize recognized her work “reclaiming African American contributions to folk and country music and bringing to light new connections between music from the past and the present,” the foundation wrote.) Giddens tells me, “My life used to be record, tour, record, tour. You can never say no as a freelance musician. I was on the road 200 days a year. If I wasn’t touring, I wasn’t making money. When I got the MacArthur, I could get off that hamster wheel. It meant I didn’t have to do anything.”

Actually, it liberated her to do a great many things: compose music for a ballet based on the theory that the “Dark Lady” of Shakespeare’s sonnets was a black brothel owner named Lucy Negro (the Nashville Ballet gave the premiere in February); write an opera for Charleston, South Carolina’s 2020 Spoleto Festival, based on the life of the Senegalese-born Islamic scholar Omar Ibn Said, who was later enslaved in the Carolinas; and host a ten-part podcast, produced by the Metropolitan Opera and New York’s WQXR, about operatic arias. Then there is her long-gestating project for a musical theater piece about a horrific but little-known episode in U.S. history: the Wilmington insurrection of 1898, in which a gang of white supremacists overthrew the progressive, racially mixed local government of Wilmington, North Carolina, murdering dozens of blacks. Such distant deadlines and grand ambitions mean months of solitary work in her home in Ireland, a luxury few folk singers can afford.

That evening in Greensboro, Giddens saunters onstage barefoot, magenta-streaked hair hanging past a somber face, and paces a bit as if lost in her own thoughts. An emcee introduces her as “the girl who came home for the weekend,” and the virtually all-white crowd jumps to its feet.

“I don’t know why y’all are trying to make me cry. We haven’t even started,” she says in a Piedmont drawl that comes and goes, depending on whom she’s talking to. Then she strums her banjo and starts on a journey from introverted ballads to moments of rapturous abandon. There’s a buzzing grain of sand in her voice, a signature that allows her to change timbre at will yet remain instantly recognizable. In the course of a single number, she slips from a sassy blues to a trumpeting, indignant holler to a high, soft coo and a low-down snarl. Giddens gives each tune its own distinctive color, mixing luscious lyricism with a dangerous bite. It’s her sense of rhythm, though, that gives her singing its energy, the way she’ll lag just behind the beat, then pounce ahead, endowing simple patterns with shifting drama and doling out charisma with playful, bighearted generosity.

* * *

If the current chapter of Giddens’ career can be said to have a start date, it is 2005, when, a few years out of college and beginning to investigate Appalachia’s intricate musical heritage, she attended the Black Banjo Gathering, a music-and-scholarship conference held at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. There she met two other musicians with a yen to rejuvenate traditions, Dom Flemons and Justin Robinson. Together they formed the Carolina Chocolate Drops, an old-time string band, and declared themselves disciples of Joe Thompson, an octogenarian fiddler from Mebane, North Carolina. These new friendships, along with increasing quasi-academic meet-ups and Thompson’s informal coaching, helped crystallize for Giddens the truth that blacks were present at the birth of American folk music, just as they were at the beginnings of jazz, blues, rock and virtually every other major genre in the nation’s musical history. This reality, though, has long been obscured by habit and prejudice. “There was such hostility to the idea of a banjo being a black instrument,” Giddens recalls. “It was co-opted by this white supremacist notion that old-time music was the inheritance of white America,” Giddens says.

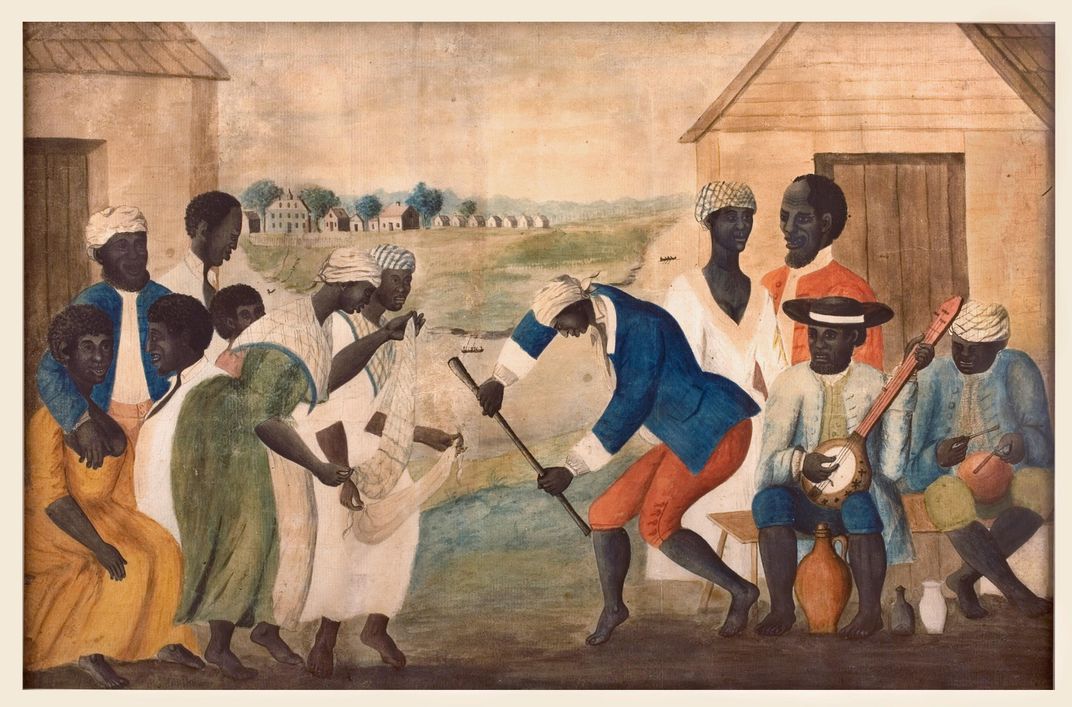

In the early 20th century, when the story of American music was first being codified, researchers and record companies systematically ignored black rural traditions of fiddling and banjo playing. But the banjo’s origins date back at least to late 17th-century Jamaica, where an Irish physician, Sir Hans Sloane, heard—and later drew—an instrument with animal skin stretched over a gourd and a long neck strung with horsehair. The basic design of that homemade banjo, which descended from African forebears, spread quickly, and by the 18th century, versions of these round-bodied, plucked-string resonators were found in black communities along the coast from Suriname to New York City. It was only in the 1840s that the banjo seeped into white culture. By the early 1900s, blacks were moving to cities en masse, leaving the instrument behind. And that’s when white musicians commandeered it as an icon of the nation’s agrarian roots.

Hoping to learn more about African musical traditions and maybe even trace her own sensibility to its origin, Giddens traveled to Senegal and Gambia—only to discover that her musical roots lay closer to home. “When I went to Africa, to them I was white. And I realized, I ain’t African,” she says. “I need to go to my own country.” Around that time, Adams, of the Smithsonian, and a companion, played a replica 19th-century banjo for Giddens. With its wooden hoop covered by animal skin, its fretless neck and gut strings, the minstrel banjo has a mellow, intimate sound, more like a lute or an Arabic oud than the bright, steel-stringed instrument that twangs through the soundtrack of Americana. Eventually, Giddens bought a replica of an 1858 banjo, and it led her forward into the past. “That was her gateway to understanding how interconnected we all are,” says Adams. “She’s legitimized this version of the banjo. Nobody else has been able to do that.”

In the long American tradition of picking up tunes wherever they happen to lie, dusting them off, and making them fresh, Giddens has turned to Briggs’ Banjo Instructor, an 1855 manual collecting the notations of Thomas Briggs, a white musician who reportedly visited Southern plantations and jotted down tunes he heard in the slave quarters. Giddens fitted Briggs’ melody “Git Up in de Mornin” with lyrics that chronicle the struggles of slaves and free blacks to educate themselves; she has renamed the song “Better Git Yer Learnin.’”

The Banjo's Evolution

The centerpiece of America’s musical tradition draws on diverse cultural influences, from West Africa to the Spanish and Portuguese empires (Research by Anna White; illustrations by Elizabeth M. LaDuke)

Akonting | West Africa

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/b2/b5b21b58-fd2d-4184-9332-834caa43d209/mar2019_h15_rhiannongiddens.jpg)

With a long, circular neck, a body made from a hollow calabash gourd and a sound-plane of stretched goat skin, the three-stringed akonting is one of 80 lutes from West Africa that scholars have identified as early banjo predecessors. But unlike many others, it was traditionally a folk instrument, played not by griots, or trained singer-musicians of high social status entrusted with oral traditions, but by regular Jola tribespeople—millions of whom, abducted and sold into slavery from their native Senegambia, brought their traditions to the New World.

Early Gourd Banjo | Caribbean islands

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/15/d5155476-a0ba-45f1-ab76-0ee477f4dbcc/mar2019_h16_rhiannongiddens.jpg)

In the 17th century, Caribbean slaves of West African origin and their descendants began to combine features of lutes like the akonting with those of the 12-stringed vihuela de mano, the guitar-like instrument of Spanish and Portuguese settlers. These new “early gourd banjos” typically had a gourd-and-hide body and three long strings plus a short fourth “thumb string,” but the neck was now flat and crowned with tuning pegs. The new instrument became an early example of Creolization, in which Afro-Carribbean slaves mixed traditions from their captors and colonizers to form their own culture.

Modern Banjo | North America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/e9/f5e9263a-981b-4b12-bf1b-ab3a92ce5e74/mar2019_h14_rhiannongiddens.jpg)

The banjo as we know it emerged on the American mainland in the mid-19th century, around the time that Virginia-born Joel Walker “Joe” Sweeney was popularizing the instrument in blackface performances from the Carolinas to New York. By the 1840s, mostly white instrument-makers began to stretch animal hide over bodies of wood that had been steam-bent into cylinders, producing a range of styles: fretless banjos, four-string “tenor” styles, even a banjo-ukulele hybrid. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the five-string banjo, outfitted with an elaborate, fretted neck, became a mainstay of ragtime, jazz, Dixieland and orchestra in the era before bluegrass.

It’s a testament to Giddens’ willingness to look the past in the eye that she invokes Briggs, one of many whites who performed in minstrel shows. Those wildly popular blackface entertainments relied on a central paradox: The music had to be black enough to seem authentic and sanitized enough to make white audiences comfortable. “His fine features and his genial smile were white through the veil of cork,” one observer wrote of Briggs in 1858.

The minstrel tradition, cartoonish and offensive as it was, still has plenty to offer the contemporary scholar and musician. Giddens takes out her phone and scrolls through images of mid-19th-century posters and covers of song collections. Even 150 years later, the illustrations are shockingly racist, but Giddens appears to hardly even see that. Instead, she’s hunting for clues to the local traditions that minstrel shows exploited and satirized: banjo, tambourine and fiddle tunes and techniques, dances and rituals that varied from county to county or even from one plantation to its neighbor. “The method books took something that was different for everyone and standardized it,” she says. The nasty iconography of minstrel music may be one reason why black musicians were not eager to celebrate the old songs and the banjo, and instead largely moved on to new styles and instruments. “Blacks have not clung to minstrelsy for obvious reason, so some of this stuff gets missed.”

By the 20th century, the classic five-string banjo had faded from African-American culture as an increasingly professional generation of black musicians migrated to guitar, brass and piano. Whites continued to play the banjo as part of a broadly nostalgic movement, but blacks couldn’t muster much wistfulness for the rural South. A few black groups, such as the Mississippi Sheiks, kept the string band tradition alive in the 1920s and ’30s, but white-oriented hillbilly bands, even those with black fiddlers, guitarists and mandolinists, included virtually no black banjo players. One rare standout was Gus Cannon, an eclectic entertainer who played blues and ragtime on the vaudeville circuit, navigating treacherous waters where art and satire mixed. But even Cannon’s performances were layered with racial and cultural ironies. Dom Flemons, of the Chocolate Drops, admiringly refers to Cannon as a “black man in blackface performing as Banjo Joe.”

Another holdover was Uncle John Scruggs, who is known almost completely from a short film shot in 1928. The elderly Scruggs sits on a rickety chair in front of a collapsing shack and plucks out a quickstep tune, “Little Log Cabin in the Lane,” while a passel of barefoot children dance. It all looks very spontaneous so long as you don’t intuit the presence of a Fox Movietone News crew behind the camera, ushering a few more picturesquely bedraggled kids into the frame. By this time, the music business’s apparatus was so well developed that it was hard for even genuine traditions to be pure. Cannon’s recordings and the film of Scruggs fed the minstrel revival of the 1920s, twice removed from the reality of rural music in the 19th century. But they’re all we’ve got.

* * *

Giddens steps into this speculative void with her own idiosyncratic brand of folklore. The vintage sound of her instrument and the old-time tinge in her voice can make it difficult to tell the difference between her excavations and her creations. But her sensibility is unmistakably 21st century. One of her best-known songs is “Julie,” drawn from an account she read in The Slaves’ War, a 2008 anthology of oral histories, letters, diaries and other first-person accounts by slaves of the Civil War. The song features a deceptively amiable dialogue between two Southern women on a veranda watching Union soldiers approach. The panicked white woman urges her chattel to run, then changes her mind: No, stay, she begs, and lie to the Union soldiers about who owns the trunkful of treasure in the house. But the black woman, Julie, won’t have it. “That trunk of gold / Is what you got when my children you sold,” she sings. “Mistress, oh mistress / I wish you well / But in leavin’ here, I’m leavin’ hell.”

For Giddens, the banjo is not just a tool for remembering the past but a way to project herself back into it, to try on the identities of ancestors whose lives she can reach only through musical imagination. “I’m interested in the interiors of these characters,” she says. “I don’t worry about whether it sounds authentic.” More precisely, Giddens treats authenticity as a quality to be pursued but never achieved. That interplay of history and imagination has also yielded Songs of Our Native Daughters, which gathers the banjo-playing African-American singer-songwriters Amythyst Kiah, Allison Russell and Leyla McCalla (also a veteran of the Carolina Chocolate Drops) to pay tribute to history’s forgotten women—slaves, singers, resisters, Reconstruction-era teachers. One song tells the story of black folk hero John Henry’s wife, Polly Ann, also a steel driver. Another takes the perspective of a child who watches his enslaved mother hanged for killing her overseer after she was repeatedly raped. At the intersection of racism and misogyny, Giddens writes in the liner notes, “stands the African American woman, used, abused, ignored, and scorned.”

Songs of Our Native Daughters was born from two similar, but separate, epiphanies. The first took place at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, where Giddens was gobsmacked to read a bitter snippet of verse by the British poet William Cowper: “I own I am shocked at the purchase of slaves / And fear those who buy them and sell them are knaves.../ I pity them greatly but I must be mum / For how could we do without sugar and rum?” The idea ended up in the song “Barbados,” where Cowper’s satire about exploitation is extended to today: “I pity them greatly, but I must be mum / For what about nickel, cobalt, lithium / The garments we wear, the electronics we own / What—give up our tablets, our laptops and phones?”

The other provocative moment was during The Birth of a Nation, the 2016 movie about Nat Turner. “One of the enslaved women on the plantation is forced to make herself available for a rape by the plantation owner’s friend,” Giddens writes in the liner notes. “Afterwards, she leaves his room, in shame, while the others look on. The gaze of the camera, however, does not rest on her, the victim’s face. It rests on her husband, the man who was ‘wronged.’...I found myself furious . . . at her own emotion and reaction being literally written out of the frame.”

With Songs of Our Native Daughters, Giddens alchemized that fury into art. Americans of all colors created a brand-new musical culture, what Giddens describes as “an experiment that’s unequaled anywhere.” To force a simple, palatable narrative onto such a complex and varied legacy is a form of betrayal. “I just want a clearer, more nuanced picture of what American music is,” she tells me. “It came out of something horrible, but what did all those people die for if we don’t tell their story?”

* * *

A week after the Greensboro concert, I meet Giddens again, this time in North Adams, Massachusetts, where she is scheduled to debut a new, half-hour suite commissioned by the FreshGrass Festival. “We put it together this afternoon,” she tells me with impressive nonchalance. One of the band members flew in just minutes before the show.

That evening, she’s barefoot as usual, wearing a flowing purple dress. After warming up with a few familiar numbers, Giddens nervously introduces the centerpiece of the program. “As I was researching slavery in America, as you do in your spare time,” she jokes, eliciting an appreciative holler from an audience member, “I got this book about Cuba and its music, and the first four chapters go back to the Arabic slave trade.” The new piece is barely 12 hours old, yet it brings antiquity alive: Slave girls in medieval North Africa were valued, and sold, for the thousands of tunes they knew by heart—“they were like living jukeboxes,” Giddens remarks, with a mixture of pity and professional admiration. Then Turrisi picks up a large-bodied “cello banjo” and plucks out a quiet, vaguely Arabic lead-in. “Ten thousand stories, ten thousand songs,” Giddens begins, her voice filled with sorrow and gold. “Ten thousand worries, ten thousand wrongs.” The incantation floats through the outdoor hush, and as the keening energy of her sound wanes into a tender coo, you can hear centuries of lament, and consolation, mingling in the warm late summer night.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(607x1689:608x1690)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/46/3946116e-9fc0-4cd5-8bdd-679eb0126391/mar2019_horizontal_rhiannongiddens.jpg)