Richard Dreyfuss on Being Bernie Madoff

The versatile actor opens up about playing the banker in a new television miniseries and his close encounters with sharks and space aliens

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/da/b3daa451-666e-4849-9b1c-0f3543349953/janfeb2016_d01_rosenbaumdreyfuss-web-resize.jpg)

He was very familiar to me,” Richard Dreyfuss tells me. “I was raised in Bayside on 218th Street. Bernie lived in Bayside too. He moved in after we moved out...but Bayside was Bayside.”

Now one Bayside, Queens, boy who made good with movies like Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind is coming out of self-described retirement to play the other Bayside boy who went very, very bad (the ABC miniseries “Madoff” premieres February 3). Dreyfuss’ movies made billions for other people; Madoff’s Ponzi schemes moved illegal billions for himself and the clients he defrauded.

Bayside boy Dreyfuss likes old-style New York luncheonettes, so we’re meeting at what Dreyfuss calls his “home base” in the city, one of the last luncheonettes in Manhattan, the Viand on Broadway and 75th. (He lives in San Diego.)

What a clash—or confluence—of characters. Dreyfuss himself is fascinated by the parallel biographical paths—and the psychological paths too.

Madoff, Dreyfuss believes, “is a sociopath and that’s a very distinctive thing [from a psychopath]. He never once thinks of, considers, even frames an image of his victims.”

“While a psychopath is someone who enjoys doing it?” I ask.

“I don’t know the medical definition. I know that psychopaths are people who are usually violent. Bernie was not like that. My dad once told me, ‘There’s three types of people. Moral people know the difference between right and wrong and do right. Immoral people know right and wrong and choose to do wrong. Amoral people don’t know the difference.’

“So maybe you can say Madoff is amoral. In the same way people who robbed banks didn’t say, ‘I’m taking money from the blacksmith.’ They just took the money. And he was really good at it.

“There’s a speech in Othello,” says Dreyfuss, who has played a lot of Shakespeare over the course of his career, “where Iago turns to the audience and, as I see it, basically says, ‘I could stop now, but I just realized how good I am at this. I am really good at this. And I know why the gods are gods and I want to be one of them. I’m going to keep doing this because it’s cosmic.’ His evil becomes outrageous and in a way it stops being just Othello and he tries to destroy the society that Othello’s part of. And he has no regrets.”

Dreyfuss seems to be asking us to consider Bernie from Bayside as more than just another grifter, scam artist, con man, but something virtually Shakespearean, cosmic in its magnitude.

It’s certainly a large-scale challenge for an actor who had made his name playing regular, all-American guys. All-American regular guys who, yes, get threatened by giant man-eating monsters of the deep and seemingly friendly aliens who get their kicks kidnapping humans. This time, Bernie’s the monster, the silent predator consuming innocents.

But these were the questions—good versus evil, psychopath versus sociopath—that Dreyfuss was immersed in from the time he was a kid growing up in Bayside. “On my street,” he recalls, “it was intensely political. These were all young veterans, most of whom had fought Hitler in two wars.”

By “two wars” he means World War II and the Spanish Civil War, whose American volunteer legion of anti-fascist forces, the Abraham Lincoln Brigades, were eulogized by Hemingway in For Whom the Bell Tolls. “They were intense socialists or communists,” Dreyfuss remembers, more idealists than ideologues. “They were the most important men in shaping my moral character. And I remember getting into a discussion with one of them and I said, ‘I get it, I get it! Your totalitarian psychopath is better than his totalitarian psychopath.’”

The Hitler versus Stalin argument. Who was more psychopathic? Who was more evil?

These discussions often turned on lesser issues: “I said to my mom once, ‘Why were you a socialist and not a communist?’ And she said, ‘Better doughnuts.’”

“OK. So you and Bernie lived in the same neighborhood, but what’s that have to do with him being a sociopath?”

“Well, it’s all in the [Arthur Miller] play All My Sons,” replies Dreyfuss. “If you want to understand Bernie, read All My Sons. If he didn’t get caught early and didn’t blow his brains out, that guy would have grown into Bernie Madoff. And would have handed his sons the company.”

The question then arises: Was Bernie an aberration from, or a natural extension of, the American business ethos?

Dreyfuss recalls getting his family in trouble with the FBI, when they were doing a security investigation

“The FBI came to our house and interviewed me and my mother. And then they said, ‘Your father’s making gun shields for the Navy. Does that breed any discontent in the home?’ And being a wise guy, I said, ‘No, no, no. My father helps the anti-war effort by making his gun shields badly.’”

Not a smart time to be a wise guy, though playing a wise guy made Dreyfuss a movie star. Later he’d become the youngest person to win a Best Actor Oscar, for The Goodbye Girl, an early rom-com. But the film that made him a major star was The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, based on a novel by the Canadian writer Mordecai Richler. A portrait of a wise guy who wants more than anything to “make it,” whatever it is. Dreyfuss’ performance—edgy, buzzing with electricity—took him to another level. Kravitz knocked people out. One of those people was Steven Spielberg, who put him into Jaws and Close Encounters.

“Pauline Kael [the legendary film critic of the New Yorker] gave me the curse of a great review. She said that no matter what Richard Dreyfuss does for the rest of his life, he will never be as good as he is in this film.”

And Duddy is still with him. There was a point in the making of the miniseries when Dreyfuss realized the connection. “I’m doing a scene in this movie and I was listening to an older adviser. And all of a sudden I realize—that that was Duddy! This is the end story of Duddy. Because Duddy was not interested in morality—he was interested in making it.”

The end story of Madoff is a life term in prison on various fraud charges and a tragedy for his “investors” and his family—one of his sons committed suicide.

So it depends, of course, on how you define making it. Does pulling off what has been described as the biggest con game in American history constitute making it?

Was Bernie a lone sociopath or is there something wrong with a society, a culture, a government that enabled Bernie (and his victims) to thrive for so long? That’s what Dreyfuss thinks he can answer. Can remedy even. (He has a plan.)

But for the moment Dreyfuss is on a roll with Bernie, seems to take delight in telling you about Bernie, and especially the moment Bernie became Bernie. Dreyfuss thinks it was a specific maneuver, a brilliant trick that saved his ass and made his fortune, that discloses the secret of Bernie’s ignoble success. “At a certain moment, he was doing really well,” making a good living, seeming to make good money for his clients. “Then there was a crash and his clients were farmisht,” he says, using the Yiddish word for all shaken up. “But he had enough money to cover those losses. So he called all of his clients and he said, ‘Don’t worry. I got you out early.’ This really happened. And he had 72 cents left in his bank account. But the respect that he got from his clients and the word of mouth about this young kid was sky-high.”

“So the whole thing really started with him keeping his clients ‘safe’?”

“Right, kept them safe.”

That was it. Who else in the world, especially in the world of business and “flash crashes,” kept you safe? Bernie kept you safe. And people stopped asking questions about how he kept getting higher and higher returns on their money. Because it was safe.

Except, of course, it wasn’t. Because at some point Bernie stopped investing in stocks for his clients. He just took in truckloads of new investor money and paid “returns” to the older investors from the incoming money (after a hefty cut for himself) and sent them all phony lists of stocks, investments they were supposedly profiting on that he never bought for them. They had nothing.

And the people in the government agencies who were supposed to keep them safe from frauds like Madoff?

“He knew it only took one call and he was a dead man,” Dreyfuss says.

One phone call?

“At one point in the SEC investigation somebody said to him, ‘Oh, the only thing you need is a DTC account number.’”

“And Bernie knew that was it. He was toast. Because the DTC is the place where every stock trade is registered. And they would have called and said, ‘Can you give us the Madoff trades?’ And they would have said, ‘We have none.’”

“But they never made the call.”

“They never made the call. Part of our drama is in the time between the asking for those numbers and when the SEC says, ‘You’ve been cleared, you’re fine.’ And he knew it only took one call.”

Dreyfuss blames two factors, two co-conspirators in Bernie’s “success.” First, the banks. “As Bernie said a million times, ‘I could never do this alone. My bank knew all the time.’ The bank knew he had parked millions of dollars for 20 years in his accounts.” In one of the aftermaths, JPMorgan ultimately paid more than $2 billion in legal settlements for ignoring “red flags” about Madoff’s dealings.

**********

The other culprit Dreyfuss points his finger at: the Securities and Exchange Commission.

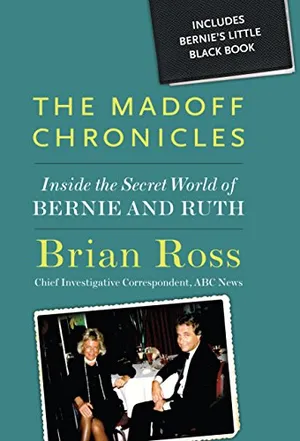

“There was an article in Barron’s,” Dreyfuss says. “Then, even when an analyst named Harry Markopolos handed the SEC a report that said ‘The World’s Largest Hedge Fund Is a Fraud,’ they didn’t nail Madoff.” (The miniseries is based on The Madoff Chronicles, a book by ABC News investigative reporter Brian Ross.)

So Bernie was Duddy Kravitz on steroids, but in another, more sinister way, he was a financial system version of Jaws. This unseen threat to safety that the financial community—like the beach town authorities in Jaws—was in denial about. Or worse, kept it secret from the people they were being paid to protect.

Our sandwich order arrives at the luncheonette booth.

At about this point, Dreyfuss told me a story about Jaws I’d never heard before—about what he calls “the linchpin” of the film. Do you remember the searing monologue delivered by Quint, the Ahab-like shark hunter, the story about the source of his hatred of the mindless eating machines?

Quint was obsessed with the hideous fate of the crew of the USS Indianapolis after it was sunk off Okinawa near the end of World War II, when 900 or so men were left struggling for life in the waves. And how, as Quint described it, they were set upon by a bloodthirsty horde of sharks who mercilessly tore them to pieces in a frenzied attack that massacred and devoured many of them?

Yes, it explains Quint’s motivation and in a way makes Jaws Spielberg’s Moby-Dick.

But there’s more to the story. The reason the Indianapolis was in the location where it sunk was that it was returning from a staging area where it had carried components of the atomic bomb that devastated Hiroshima.

It wasn’t in Peter Benchley’s book, the novel that was the source for Jaws, Dreyfuss says. But when Spielberg learned about it, “he put the monologue in the movie and it became the linchpin of the story.” It was like the radioactive core of dread that spread through the film. And infused Quint’s monologue with its dark passion.

There have been several conflicting accounts about the making of that monologue. Dreyfuss says multiple people contributed. “All of Steven’s friends—Francis [Ford Coppola], Marty Scorsese, myself, Robert Shaw—we all tried our hand at it.” But ultimately “it was his.” (Spielberg himself has given credit to “several others.”)

**********

“So you understand this guy’s obsession,” Dreyfuss continues, “and you understand a hatred of sharks, which was unfortunate because Peter Benchley died with a broken heart. He really tried desperately not to let this become a worldwide anti-shark hysteria—which it did.”

Benchley’s love of what he made people fear was ironic and strange. But stranger in a way, Dreyfuss says, was Spielberg’s attempt to get us to love the aliens that science fiction and monster movies made us fear.

I’d always thought Close Encounters was one of the most ambitious films ever made. Say what you want about it as a film, but the bottom line is that Steven Spielberg was trying in his own way to signal the entire cosmos that aliens should be welcomed by humans. And he was trying to prepare mankind to view with anticipation and wonder the possibility of alien visitors.

He was trying to set up an intergalactic hookup.

Dreyfuss agrees with this, but he has another take I hadn’t thought of. He believes that if it had not been for timing, Close Encounters might have changed our entire history and culture.

He’s referring to the fact that in 1977 George Lucas’ Star Wars debuted seven months earlier than Close Encounters. And suddenly changed the world in a way that Close Encounters might have. In a different way actually.

“George and Steven are best friends and when we were still shooting, [Lucas] had just finished in England, and he came to our set. And I remember we were all out to dinner one night and he [Lucas] was sitting there glum. And I said, ‘What’s the matter?’ And he said, ‘I made it [Star Wars] dumb for kids.’ And then I saw both films. And sure enough, George made a film for kids, while Close Encounters was made for adults. But Star Wars had seized the territory first.”

The territory being a visionary awe of the cosmos, and the potential for contact, versus comic book space opera-style villains. The soulful, obsessive longing Dreyfuss embodied in Close Encounters as Roy Neary, the everyman who went off with the aliens, lacked the comic book impact. “If Close Encounters had opened first,” Dreyfuss contends, “the idea of space and stories about aliens would have been lifted to a certain level of audience maturity. And I think that some of the great writers and some of the great screenwriters and directors would have been making films in that genre as opposed to bang-bang Star Wars and Star Wars sequels. Close Encounters was, from the beginning to the end, about something far more intelligent, or intellectual, or uplifting. It was mature. You remember the first ad line? The first ad line for Close Encounters was ‘You have nothing to fear by looking up.’”

Dreyfuss is still a believer. Not necessarily in UFO’s (“I’m agnostic,” he says) but what they represented or were represented as in the film.

“In a way, it’s also about race, wasn’t it?” I asked. “That we’re all one race?”

“Definitely.”

“Did you guys talk about that?”

“It was already in the culture that one of the astronauts had looked back [at the earth] and it changed his life. He had become a human as opposed to an American. He looked at the earth and he realized we’re all one thing.”

And Spielberg was trying to say even the aliens weren’t aliens. We’re “all one thing” with them too. Eerily apropos in this moment of concern about “illegal aliens.”

Dreyfuss and Spielberg talked about the mission of Close Encounters during the filming of Jaws.

“And that’s when it became clear to me—I vowed I was going to play this part no matter what. And so I used to bad-mouth every actor in Hollywood. And I openly did. I said to Spielberg, ‘Pacino’s crazy. Jack Nicholson has no sense of humor.’ I said weird things. And then finally one day I said ‘Steven, you need a child [for the role].’ And he looked up and he said, ‘You’ve got the part.’ Because I knew, however much of an adult and a family man he was, he [Roy Neary] had to have a childlike wonder. And that’s what they hired me for, in those days. Literally. They used to hire me for this.”

He looks up to the ceiling of the luncheonette, posing. A look of awestruck wonder.

So maybe it’s appropriate that he still has some questions he’d like to ask Spielberg’s aliens. Maybe what bothers him most is, “Why don’t they ever go to Washington?”

Where they could talk civics.

This is the thing about Richard Dreyfuss. You can’t understand him these days without understanding his obsession with civics. He says it’s why he quit seeking major film roles ten years ago.

He’s part Duddy Kravitz and part earnest Roy Neary. But he’s also, at heart, still someone who takes abstract political discussion as seriously as his boyhood heroes in Bayside did. The Dreyfuss Civics Initiative is his true passion these days. Raising money to teach the Constitution in schools. The red diaper baby (the nickname for children of reds) has grown up to believe deeply in the brilliance of the Constitution and that what’s really wrong with America, and the world for that matter, is that no one any longer teaches or studies the values of the Constitution.

Pursuing this vision, he spent considerable time studying political philosophy at Oxford (true!) and trying to drum up support for what he believes is the only thing that can save us, the planet from self-destruction.

“I was basically studying the damage that was being done by the absence of teaching civic authority and Enlightenment values. And I took it very personally. I was afraid for my children. So I quit. And I quit and then I met Svetlana,” his third wife, a Russian émigré—he says she’s the daughter of a KGB big shot—who told him what living under a reign devoid of civics was like, even for the privileged.

He’s one of those impassioned autodidacts on the subject. It turns out he just completed (“hot off the computer,” he says) a long play called Appomattox about the misrepresentation of Reconstruction (something Taylor Branch, Ta-Nehisi Coates and other historians have been exposing). Dreyfuss’ inspiration: His voice used to be the booming recorded voice narrating the Gettysburg Battlefield cyclorama. And he found himself outraged at what he believed was the “moral equivalence” being preached there—the uneasy equation of fighters to preserve slavery with those who fought for their freedom.

And so he’s promoting all these programs to encourage civics education and Enlightenment values at a time when Enlightenment values—tolerance, free speech and the like—are under attack by sectarian values in the world. He seems to assume everyone will come out believing in the same centrist liberal values he does, despite deeply conservative believers in constitutionalism such as Antonin Scalia and talk show hosts like Mark Levin who come out on the opposite side of constitutional issues. And religious believers who look to a higher authority than the Constitution.

“You’ve got to protect the system of secular faith in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights and Enlightenment values,” he says. “That way you can protect all religions.”

But what’s appealing about him is that, despite his near-religious devotion to rational values, he also has a belief in the irrational, the miraculous. He tells a miracle story that gives me chills.

“In 1982,” he recalls, “I was a famous movie star; I was rich and I was acting like a low-down dirty dog. I was taking drugs; I was sleeping with people’s wives; I was out of control. And one night, at the home of a studio head, I screamed obscenities in her face and then left and got into my two-seater convertible Mercedes with the top down and drove down the street. I never put a seatbelt on, I never had. And I woke up with the Benedict Canyon on my face; the car was above me, and I was strapped in by a safety belt I didn’t put on. And I knew my life had changed.”

He’s sort of saying he was saved by a personal angel who led him to the light.

“Yeah. And I was arrested for possession of a little bit of coke and two or three Percodan tablets. And I had flipped my car—I had slammed into one of the big trees on Benedict and half the divider slammed into the thing, the car rolled, and I woke up...”

“And you had your safety belt on.”

“I didn’t put it on myself.”

Safety. The most valuable thing in the world. Ask Bernie.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)