Rio’s Music is Alive and Well

Brazil’s music scene may be known for beats such as bossa nova, but newer sounds are making waves on the streets of Rio

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rio-Music-samba-singers-and-composers-631.jpg)

On any given night in Rio de Janeiro, music lovers young and old mill in and out of nondescript bars and cafés in Lapa, a bohemian neighborhood of 19th-century buildings with shutter-flanked windows and flowery, wrought iron balconies. Strolling amid street vendors selling caipirinhas, Brazil’s signature lime and cachaça drink, visitors have come in search of samba and choro, the country’s traditional music currently enjoying a cultural resurgence. Late into the night, choro’s melodic instrumentations mingle with the swaying rhythms of 1940s-style samba to create an aural paean to Brazil’s musical past.

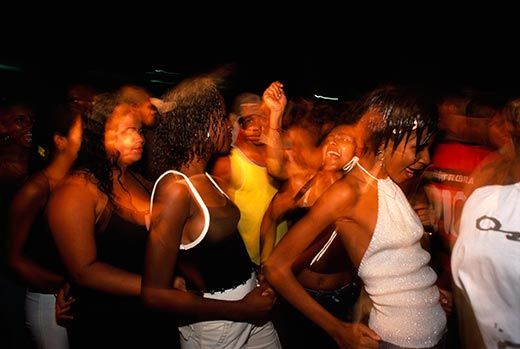

On the outskirts of the city in the favelas, or shantytowns, thousands of young partygoers crowd into quadras, community squares, for a “baile funk,” a street dance set to Rio’s thumping popular funk music. An amalgamation of Brazilian genres, Afro-Brazilian beats and African-American soul and hip-hop, baile funk makes the ground pulsate almost as much as the bodies of the gyrating dancers.

The samba and choro revival in Lapa and favela funk are just two facets of Rio’s vast musical landscape, which includes Brazilian jazz, bossa nova, hip-hop, Afro-Caribbean fusion and more. Choro musicians celebrate Brazil’s musical heritage while adding new twists of their own; the favelas’ funk co-opts foreign and native influences to make a style of music distinct from any other.

Samba and Choro

As musicians, locals and tourists converge in Lapa, it has become the musical heart of Rio de Janeiro. But in the early 1980s, when American composer and music educator Cliff Korman first traveled to Rio de Janeiro, he could find few people interested in playing Brazilian music (tourists spots favored jazz and American pop music). It was Paulo Moura, a Latin Grammy-award winner who died at age 77 this year, who introduced Korman to rodas de choro, or choro circles. At these weekly or monthly jam sessions, friends would bring their guitars, clarinets and pandeiros (a Brazilian tambourine-like instrument) to play this 150-year-old, classically derived music. Infused with Afro-Brazilian syncopated rhythms, choro—a name derived from the Portuguese verb chorar, to cry, has an emotive, even melancholy quality despite its often up-tempo rhythms.

At the time of Korman’s visit, Lapa was not a place many people frequented. Though the historic district had been a mecca for samba in the 1930s, it had fallen into decay and become a haven for prostitution. “It has traditionally been a kind of down-at-the-heels bohemian neighborhood,” says Bryan McCann, a professor of Brazilian studies at Georgetown University.

In the ’90s, a small, macrobiotic restaurant in Lapa called Semente started featuring samba vocalist Teresa Cristina and her Grupo Semente. Word spread and soon the group was drawing listeners from around the city. “This restaurant was the seed that sprouted the whole movement of samba again,” says Irene Walsh, an American singer and filmmaker, who is producing a documentary on samba in the Lapa district.

Slowly but surely, Lapa’s music scene blossomed as more bars and restaurants added live samba and choro acts. “Now we’re 15 years into the scene, so there’s a whole generation of musicians that have literally grown up playing in it,” says McCann. “It adds a kind of depth. What we’re getting now is not just a kind of revivalist mode, but really people who are taking this music in different directions.”

Listen to tracks from the Smithsonian Folkways album, "Songs and Dances of Brazil."

Many musicians have begun experimenting with instrumentation, including piano, drums, or even electric bass in their ensembles. Improvisation with choro is creating a new blend of sounds, a fusion of the genre with American jazz.

“We still have our own music,” musician and undersecretary of culture of Rio de Janeiro, Humberto Araújo recalls Paulo Moura telling him years ago when he studied with the master clarinetist and saxophonist decades ago. “ ‘It’s time for you to feel it,’” Moura had proclaimed to Araújo in the 1980s.

Baile Funk

Though youths living in favelas flock to Rio’s bailes funk, the scene is not likely to draw tourists. The quadras, used by samba schools in the past for Carnaval preparations, are now the turf for funk dances, where the festive spirit is matched by the threat of gang violence and drugs. The funk dances and many of the performers are sometimes funded by some of Brazil’s most infamous gangs, according to Professor Paul Sneed, an assistant professor in the Center of Latin American Studies at the University of Kansas.

Two types of funk first emerged in Rio in the 1970s: montage, a DJ-mixed layering of samples and beats from media ranging from gunshot noises to American funk recordings, and “rap happy,” which revolved around sung (not rapped) narratives by emcees. Variations evolved over the years, from a Miami hip-hop style with a bass-driven rhythm to the heavily syncopated rhythms derived from the Afro-Brazilian syncretic religions Candomble and Umbanda.

Funk lyrics, in the sub-genre called “funk sensual,” are usually sexually suggestive and provoke equally suggestive dancing. While double entendres and sexual objectification abound, funk sensual does not necessarily carry the same sexist and homophobic messages for which American hip-hop has often been criticized. Transvestites are big fans of funk and a few have become prominent performers of the music. According to Sneed, who has lived in a Rio favela, “women can assume a traditionally masculine stance [of being the pursuer] and they objectify men in a playful way.”

Another lyric subgenre is called Proibidão, which emphasizes the gangster associations of the music. Sneed says Proibidão may be increasingly popular because it speaks to the social experience of youths in the favelas. “The everyday person who’s not actually involved in a gang somehow identifies with the social banditry as a symbol of some sort of power and hope.” Whether the appeal lies in the hard-driving beats or its controversial lyrics, Rio’s favela funk scene gains more and more listeners every day.

Brazil’s musical diversity is good thing, says culture undersecretary Araújo. “I believe that every style or genre should have its own place, its own stage. Music is no longer an elite affair.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)