Ripped from the Walls (and the Headlines)

Fifteen years after the greatest art theft in modern history the mystery may be unraveling

At 1:24 a.m. on March 18, 1990, as St. Patrick’s Day stragglers wobbled home for the night, a buzzer sounded inside the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. One of two hapless museum guards answered it, saw what he thought were two Boston policemen outside the Palace Road entrance, and opened the door on the biggest art theft in U.S. history.

The intruders, who had apparently filched the uniforms, overpowered the guards and handcuffed them. They wrapped the guards’ heads in duct tape, leaving nose holes for breathing, and secured the men to posts in the basement. After disarming the museum’s video cameras, the thieves proceeded to take apart one of this country’s finest private art collections, one painstakingly assembled by the flamboyant Boston socialite Isabella Gardner at the end of the 19th century and housed since 1903 in the Venetian-style palazzo she built to display her treasures “for the education and enjoyment of the public forever.”

But as the poet Robert Burns warned long ago, the best laid schemes of mice and men “gang aft agley”—an insight no less applicable to heiresses. Less than a century elapsed before Mrs. Gardner’s high-minded plans for eternity began to crumble. Up a flight of marble stairs on the second floor, the thieves went to work in the Dutch Room, where they yanked one of Rembrandt’s earliest (1629) self-portraits off the wall. They tried to pry the painted wooden panel out of its heavy gilded frame, but when Rembrandt refused to budge, they left him on the floor, a little roughed up but remarkably sturdy at age 376. They crossed worn brown tiles to the south side of the room and cut two other Rembrandts out of their frames, including the Dutch master’s only known seascape, Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee (opposite), and a double portrait titled A Lady and Gentleman in Black (Table of Contents, p. 6). From an easel by the windows, they lifted The Concert (p. 97), a much-loved oil by Johannes Vermeer, and a Govaert Flinck landscape, long thought to have been painted by Rembrandt, whose monogram had been forged on the canvas. Before the intruders departed, they snapped up a bronze Chinese beaker from the Shang era (1200-1100 b.c.) and a Rembrandt etching, a self-portrait the size of a postage stamp.

A hundred paces down the corridor and through two galleries brimming with works by Fra Angelico, Bellini, Botticelli and Raphael, the thieves stopped in a narrow hallway known as the Short Gallery. There, under the painted gaze of Isabella Stewart Gardner herself, they helped themselves to five Degas drawings. And in a move that still baffles most investigators, they tried to wrestle a flag of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard from its frame and, failing, settled for its bronze eagle finial. Then, back on the ground floor, the thieves made one last acquisition, a jaunty Manet oil portrait of a man in a top hat, titled Chez Tortoni (p. 103). By some miracle, they left what is possibly the most valuable painting in the collection, Titian’s Europa, untouched in its third-floor gallery.

The raiders’ leisurely assault had taken nearly 90 minutes. Before departing the museum that night, they left the guards with a promise: “You’ll be hearing from us in about a year.”

But the guards never heard a word, and 15 years later the case remains unsolved, despite wide-ranging probes by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, with assists from Scotland Yard, museum directors, friendly dealers, Japanese and French au- thorities, and a posse of private investigators; despite hundreds of interviews and new offers of immunity; despite the Gardner Museum’s promise of a $5 million reward; despite a coded message the museum flashed to an anonymous tipster through the financial pages of the Boston Globe; despite oceans of ink and miles of film devoted to the subject; despite advice from psychics and a tip from an informant who claims that one of the works is rumbling around in a trailer to avoid detection.

There have been enough false sightings of the paintings— in furniture stores, seedy antiques marts and tiny apartments— to turn Elvis green with envy. In the most tantalizing of these, a Boston Herald reporter was driven to a warehouse in the middle of the night in 1997 to see what purported to be Rembrandt’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee. The reporter, Tom Mashberg, had been covering the theft and was allowed to view the painting briefly by flashlight. When he asked for proof of authenticity, he was given a vial of paint chips that were later confirmed by experts to be Dutch fragments from the 17th century—but not from the Rembrandt seascape. Then the painting, whether real or fake, melted from view again. Since then, there has been no sign of the missing works, no arrests, no plausible demands for ransom. It is as if the missing stash—now valued as high as $500 million— simply vanished into the chilly Boston night, swallowed up in the shadowy world of stolen art.

That world, peopled by small-time crooks, big-time gangsters, unscrupulous art dealers, convicted felons, money launderers, drug merchants, gunrunners and organized criminals, contributes to an underground market of an estimated $4 billion to $6 billion a year. While the trade in stolen art does not rival the black market in drugs and guns, it has become a significant part of the illicit global economy.

Some 160,000 items—including paintings, sculptures and other cultural objects—are currently listed by the Art Loss Register, an international organization established in 1991 to track lost or stolen art around the world. Among the objects on their list today are the 13 items snatched from the GardnerMuseum as well as 42 other Rembrandt paintings, 83 Rembrandt prints and an untitled painting attributed to Vermeer that has been missing since World War II. The register records more than 600 stolen Picassos and some 300 Chagalls, most of them prints. An additional 10,000 to 12,000 items are added each year, according to Alexandra Smith, operations director for the London-based registry, a company financed by insurers, leading auction houses, art dealers and trade associations.

Such registries, along with computer-based inventories maintained by the FBI and Interpol, the international police agency, make it virtually impossible for thieves or dealers to sell a purloined Van Gogh, Rembrandt or any other wellknown work on the open market. Yet the trade in stolen art remains a brisk one.

In recent years, big-ticket paintings have become a substitute for cash, passing from hand to hand as collateral for arms, drugs or other contraband, or for laundering money from criminal enterprises. “It would appear that changes in the banking laws have driven the professional thieves into the art world,” says Smith of the Art Loss Register. “With tighter banking regulations, it has become difficult for people to put big chunks of money in financial institutions without getting noticed,” she explains. “So now thieves go out and steal a painting.”

Although the theft of a Vermeer or a Cézanne may generate the headlines, the illicit art market is sustained by amateurs and minor criminals who grab targets of opportunity— the small, unspectacular watercolor, the silver inkstand, the antique vase or teapot—most from private homes.These small objects are devilishly hard to trace, easy to transport and relatively painless to fence, though the returns are low. “If you have three watercolors worth £3,000,” Smith says, “you are likely to get only £300 for them on the black market.” Even so, that market brings more money to thieves than stolen radios, laptops and similar gear. “Electronics have become so affordable that the market for them has dried up,” Smith adds, “and those who go after these things have learned that art is better money than computers.”

Smith and others who track stolen art are clearly irritated by the public’s misconception that their world is populated by swashbucklers in black turtlenecks who slip through skylights to procure paintings for secretive collectors. “I’m afraid it’s a lot more mundane than that,” says Lynne Richardson, former manager of the FBI’s National Art Crime Team. “Most things get stolen without much fanfare. In museums it’s usually somebody with access who sees something in storage, thinks it’s not being used and walks off with it.”

Glamorous or not, today’s art crooks are motivated by a complex of urges. In addition to stealing for the oldest reason of all—money—they may also be drawn by the thrill of the challenge, the hope of a ransom, the prospect of leverage in plea bargaining and the yearning for status within the criminal community. A few even do it for love, as evidenced by the case of an obsessed art connoisseur named Stephane Breitwieser. Before he was arrested in 2001, the French waiter went on a seven-year spree in Europe’s museums, amassing a collection valued as high as $1.9 billion. He reframed some of the works, cleaned them up and kept them in his mother’s small house in eastern France; there, according to court testimony, he would close the door and glory in his private collection, which included works by Bruegel, Watteau, Boucher and many others. He never sold a single piece. Finally collared in Switzerland for stealing an old bugle, he attempted suicide in jail when informed that his mother had destroyed some of his paintings to hide his crimes. Breitwieser spent two years jailed in Switzerland before being extradited to France, where he was sentenced to a 26- month prison term in January 2005.

What continues to perplex those investigating the Gardner mystery is that no single motive or pattern seems to emerge from the thousands of pages of evidence gathered over the past 15 years. Were the works taken for love, money, ransom, glory, barter, or for some tangled combination of them all? Were the raiders professionals or amateurs? Did those who pulled off the heist hang on to their booty, or has it passed into new hands in the underground economy? “I would be happy to knock it down to one or two theories,” says FBI special agent Geoffrey J. Kelly, who has been in charge of the Gardner investigation for three years. He acknowledges that the bureau has left the book open on a maddening array of possibilities, among them: that the Gardner theft was arranged by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) to raise money or to bargain for the release of jailed comrades; that it was organized by James J. “Whitey” Bulger, who was Boston’s ruling crime boss and a top-echelon FBI informant at the time of the heist; that it was inspired by Myles J. Connor Jr., an aging rocker who performed with Roy Orbison before he gained fame as New England’s leading art thief.

Connor, who claims to have pulled off no less than 30 art thefts in his career, was in jail when the GardnerMuseum was raided; but he boasts that he and a now deceased friend, Bobby Donati, cased the place several years before, and that Donati did the deed. Connor came forward after the museum increased its reward from $1 million to $5 million in 1997, saying he could find the missing artwork in exchange for immunity, part of the reward and release from prison. Authorities considered but ultimately rejected his offer. Connor believes that the Gardner spoils have passed into other, unknown hands. “I was probably told, but I don’t remember,” he says, citing a heart attack that affected his memory.

Some investigators speculate that the theft may have been carried out by amateurs who devoted more time to planning the heist than they did to marketing the booty; when the goods got too hot to handle, they may have panicked and destroyed everything. It is a prospect few wish to consider, but it could explain why the paintings have gone unseen for so long. It would also be a depressingly typical denouement: most art stolen in the United States never reappears—the recovery rate is estimated to be less than 5 percent. In Europe, where the problem has been around longer and specialized law enforcement agencies have been in place, it is about 10 percent.

Meanwhile, the FBI has managed to eliminate a few lines of inquiry into the Gardner caper. The two guards on duty at the time of the theft were interviewed and deemed too unimaginative to have pulled it off; another guard, who disappeared from work without picking up his last paycheck, had other reasons to skip town in a hurry; a former museum director who lived in the Gardner, entertaining visitors at all hours, was also questioned. He died of a heart attack in 1992, removing himself from further interrogation. Agents also interviewed a bumbling armored truck robber, as well as an exconvict from California who arrived in Boston before the theft and flew home just after it, disguised as a woman; it turned out that he had been visiting a mistress.

Special agent Kelly offers a tight smile: “There have been a lot of interesting stories associated with the case,” he says. “We try to investigate every one that seems promising.” Just the week before, in fact, he had traveled to Paris with another agent to probe rumors that a former chief of the financially troubled entertainment conglomerate Vivendi Universal had acquired the Gardner paintings, an allegation the official denies.

“In a bank robbery or an armored car robbery, the motivation is fairly easy to decipher,” says Kelly. “They want the money. The motivation in an art theft can be much more difficult to figure out.” The Gardner thieves were professional in some ways, amateurish in others: spending 90 minutes inside the museum seems unnecessarily risky, but the way they got in was clever. “It shows good planning,” says Kelly. “They had the police uniforms. They treated the guards well. That’s professional.” The thieves also knew the museum well enough to recognize that its most famous paintings were in the Dutch Room. Once there, though, they betrayed a bushleague crudeness in slashing the paintings from their frames, devaluing them in the process. “Given that they were in the museum for an hour and a half, why did they do that?” Kelly wonders.

And what of the wildly uneven range of works taken? “There doesn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason to it,” he adds. Why bother with the Degas sketches? “And to overlook Titian’s Europa? And to spend such an inordinate amount of time trying to get the Napoleonic flag off the wall and then to settle for the finial?”

Perhaps most telling—and in some ways most unsettling— is the ominous silence since March 18, 1990. Kelly believes, and most other investigators agree, that the long hush suggests professional thieves who moved their stash with efficiency and who now control it with disciplined discretion. If the thieves had been amateurs, Kelly posits, “somebody would have talked by now or somehow those paintings would have turned up.”

It is not unusual for art thieves to hang on to prominent paintings for a few years, allowing time for the public excitement and investigative fervor to fade, for the artwork to gain in value and for both federal and state statutes of limitation to run their course. As a result of the Gardner case, Senator Edward M. Kennedy introduced the “Theft of Major Artwork” provision to the 1994 Crime Act, a new law making it a federal offense to obtain by theft or fraud any object more than 100 years old and worth $5,000 or more; the law also covers any object worth at least $100,000, regardless of its age, and prohibits possession of such objects if the owner knows them to be stolen. Even with such laws in force, the FBI’s Kelly says that some criminals keep paintings indefinitely as an investment against future trouble and to bargain down charges against them, or, as he puts it, as a get-out-ofjail- free card.

“It’s quite possible the paintings are still being held as collateral in an arms deal, a drug deal or some other criminal venture,” says Dick Ellis, a prominent investigator who retired in 1999 from Scotland Yard’s highly regarded Art and Antiques Unit. “Until the debt is paid off, they will remain buried. That is why nobody has heard of the paintings for 15 years. That is a long time, but it may be a big debt.”

Wherever the paintings may be, GardnerMuseum director Anne Hawley hopes that they are being well cared for. “It is so important that the art is kept in safe condition,” she says. “The works should be kept at a steady humidity of 50 percent—not more or less—and a steady temperature of around 70 degrees Fahrenheit. They need a stable environment,” she adds, sounding like the concerned mother of a kidnapped child. “They should be kept away from light and they should be wrapped in acid-free paper.” While it is common practice for art thieves to roll up canvases for easy transport, Hawley pleads that the works be unrolled for storage to avoid flaking or cracking the paint. “Otherwise the paintings will be compromised and their value decreased. The more repainting that needs to be done when they are returned, the worse it will be for the integrity of the paintings.” (The museum had no theft insurance at the time of the heist, largely because the premiums were too high. Today the museum has not only insurance but an upgraded security and fire system.)

Like others who work in the palace Isabella Gardner built, Hawley, who had been on the job for just five months at the time of the theft, takes the loss personally. “For us, it’s like a death in the family,” she says. “Think of what it would mean to civilization if you could never hear Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony again. Think if you lost access to a crucial piece of literature like Plato’s Republic. Removing these works by Rembrandt and Vermeer is ripping something from the very fabric of civilization.”

In 1998—eight years into the investigation—Hawley and all of Boston woke up to the news that the local FBI office had been corrupted by a long partnership with Whitey Bulger, the crime boss and FBI informant who had been a suspect all along. Because Bulger and his associates had helped the FBI bring down Boston’s leading Italian crime family (which incidentally opened up new turf for Bulger), he was offered protection. Bulger happily took advantage of the opportunity to expand his criminal empire, co-opting some of his FBI handlers in the process. Abureau supervisor took payments from him, and a star agent named John Connolly warned him of impending wiretaps and shielded him from investigation by other police agencies.

When an honest prosecutor and a grand jury secretly charged Bulger in 1995 with racketeering and other crimes, Connolly tipped Bulger that an arrest was imminent, and the gangster skipped town. He has been on the run ever since. Connolly is now serving a ten-year prison sentence for conspiring with Bulger, and some 18 agents have been implicated in the scandal. As new details emerged in court proceedings, begun in 1998, the charges against Bulger have multiplied to include conspiracy, extortion, money laundering and 18 counts of murder.

Against this sordid background, it is easy to understand why some critics remain skeptical about the bureau’s ability to solve the case. “Their investigation was possibly corrupted and compromised from the start,” says the Gardner’s Hawley. “We assumed that things were proceeding according to schedule—then this came up!” While she praises Geoffrey Kelly as a diligent investigator and allows that the FBI’s Boston office has cleaned itself up, she has taken the remarkable step of inviting those with information about the Gardner theft to contact her—not the FBI. “If people are afraid to step forward or hesitant to speak with the FBI, I encourage them to contact me directly, and I will promise anonymity,” she says. “I know that there’s a child, a mother, a grandmother, or a lover—someone out there—who knows where the pieces are. Anyone who knows this has an ethical and moral responsibility to come forward.The most important thing is to get the art back, not to prosecute the people who took it.”

With that, at least, the FBI’s Kelly agrees. “The primary importance is to get the paintings back,” he says. “The secondary importance is to know where they’ve been since March 18, 1990. We want to get the message out that there is a $5 million reward, that the U.S. attorney for the district of Massachusetts has stated that he would entertain immunity negotiations for the return of the paintings. The reward, coupled with the immunity offer, really make this a good time to get these paintings back to the museum, where they belong.”

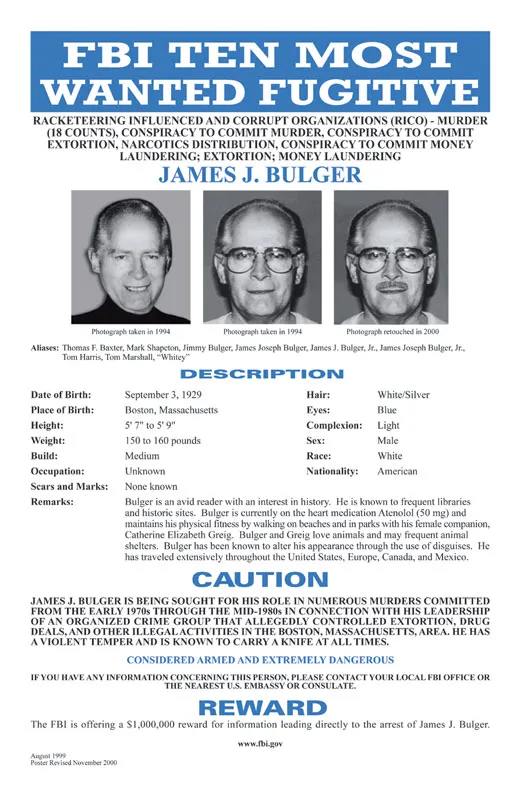

Meanwhile, the specter of Whitey Bulger continues to haunt the case. Just outside Kelly’s office, a photograph of the gangster hangs on the bureau’s Ten Most Wanted list. The possibility of Bulger’s complicity “has been around since day one,” says Kelly. “But we haven’t come across any evidence relevant to that theory.”

Might rogue agent John Connolly have tipped Bulger off about the Gardner investigation? “I am not aware of that,” Kelly answers.

With or without Connolly’s involvement, there have been reports that two Bulger associates—Joseph Murray of Charleston and Patrick Nee of South Boston—claimed they had access to the stolen paintings in the early 1990s. Both Murray and Nee, who were convicted in 1987 of attempting to smuggle guns from New England to the Irish Republican Army, have been linked to the Gardner theft by informants, but Kelly says that no evidence supports those claims. Murray is dead now, shot by his wife in 1992. And Nee, who returned to South Boston on his release from prison in 2000, denies any involvement in the theft.

“The paintings are in the West of Ireland,” says British investigator Charles Hill, “and the people holding them are a group of criminals—about the hardest, the most violent and the most difficult cases you are ever likely to encounter. They have the paintings, and they don’t know what to do with them. All we need to do is convince them to return them. I see that as my job.” Although Hill stresses that his comments are speculative, they are informed by his knowledge of the case and the characters involved.

It would be easy to dismiss Charles Hill were it not for his experience and his track record at solving hard-to-crack art cases. The son of an English mother and an American father, Hill went to work as a London constable in 1976 and rose to the rank of detective chief inspector in Scotland Yard’s Art and Antiques Unit. After a 20-year career at the yard, he retired and became a private investigator specializing in stolen art. He has been involved in a string of high-profile cases, helping to recover Titian’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt, which had been missing for seven years; Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid; Goya’s Portrait of Dona Antonia Zarate; and Edvard Munch’s The Scream, among other works. (Another version of The Scream, stolen from Oslo’s MunchMuseum last year, is still missing.)

Hill believes that the Gardner paintings arrived in Ireland sometime between 1990 and 1995, shipped there by none other than Whitey Bulger. “Being extremely clever, knowing that he could negotiate the paintings for money or for a bargaining chip, he took them,” says Hill. “Only Bulger could have done it at the time. Only Bulger had the bureau protecting him. Moving the pictures was easy—most probably in a shipping container with no explosives or drugs for a dog to sniff. He thought Ireland meant safety for him and the museum’s stuff.”

But Bulger had not bargained on being charged with multiple murders, which made him less than welcome in Ireland’s West Country and helpless to bargain down the charges against him. “He went to Ireland hoping to hide out there,” says Hill. “When they threw him out, they hung on to his things, not knowing what to do with them.”

Hill says he is in delicate negotiations that may lead him to the Irish group holding the paintings. “I have someone who says he can arrange for me to visit them,” he explains. “If you will forgive me, I would rather not tell you their names right now.” Hill adds that the group, while not part of the IRA, has links with it.

A few scraps of evidence support an Irish connection. On the night of the theft—St. Patrick’s Day—one of the intruders casually addressed a guard as “mate,” as in: “Let me have your hand, mate.” Hill thinks it unlikely that a Boston thug or any other American would use that term; it would more likely come from an Irishman, Australian or Briton. Hill also connects the eclectic array of objects stolen to the Irish love of the horse. Most of the Degas sketches were equestrian subjects, “an iconic Irish image,” he says. As for the Napoleonic flag, they settled for the finial—perhaps as a tribute of sorts to the French general who tried to link up with Irish rebels against Britain.

So in Hill’s view, all roads lead to Ireland. “It’s awful for the FBI,” he says. “When the paintings are found here, it is going to be another terrible embarrassment for them. It will show that Whitey pulled off the largest robbery of a museum in modern history—right under their noses.” Hill pauses for a moment. “Don’t be too hard on them, now.”

Back in Mrs. Gardner’s museum, the crowds come and go. On a late winter day, sunlight splashes the mottled pink walls of the palazzo’s inner court, where orchids bloom and schoolchildren sit with their sketchbooks, serenaded by water tumbling into an old stone pool placed there by Isabella Stewart Gardner. In her instructions for the museum that bears her name, she decreed that within the marble halls of her palace, each Roman statue, each French tapestry, each German silver tankard, each folding Japanese screen, and each of the hundreds of glorious paintings she loved so well should remain forever just as she had left them.

That is why today, upstairs on the second floor in the Dutch Room, where Rembrandt’s roughed up 1629 self-portrait has been returned to its rightful place on the north wall, the painter stares out across the room, his eyes wide and brows arched, regarding a ghastly blank space where his paintings ought to be. All that’s left are the empty frames.