Saddle Up With Badger Clark, America’s Forgotten Cowboy Poet

The unsung writer, known to many as “Anonymous,” led a life of indelible verse

:focal(430x255:431x256)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/ca/e1caaba6-f1d8-4c47-b962-010791136e7f/4.jpg)

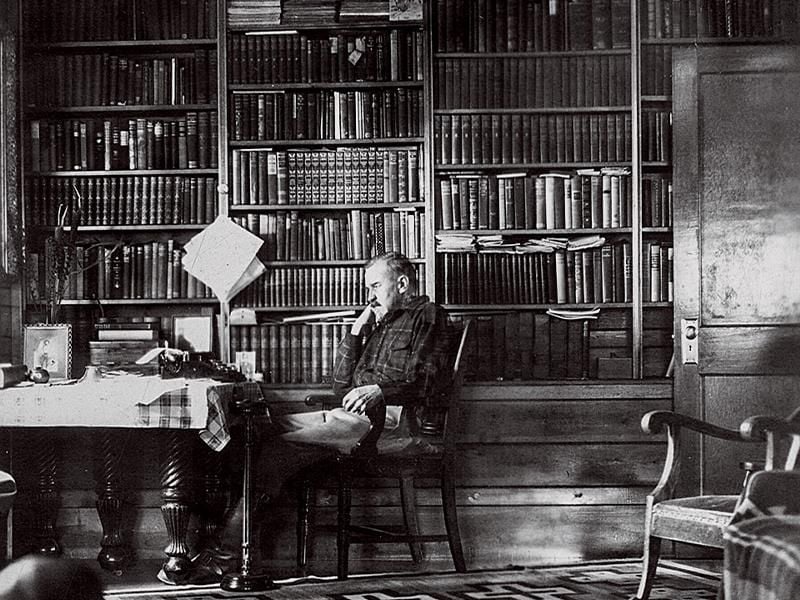

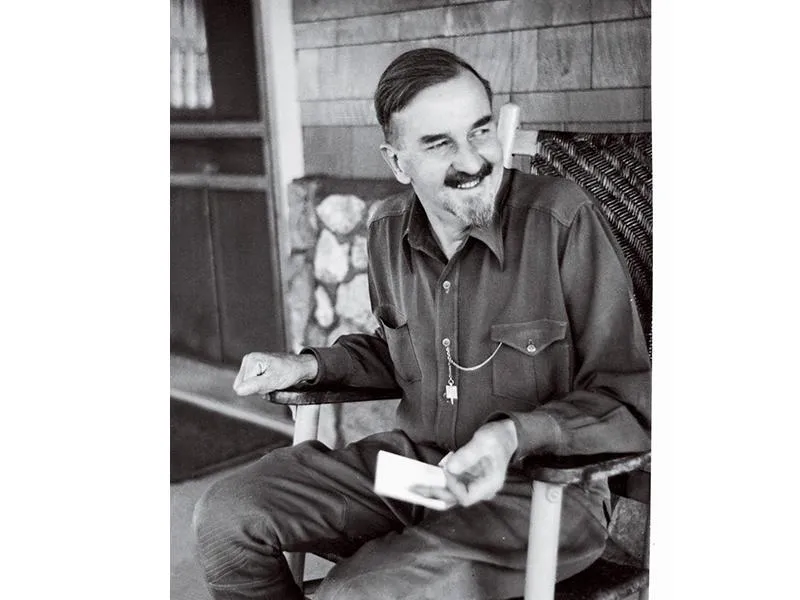

South Dakota’s first poet laureate lived much of his life alone in a prim cabin in the heart of Custer State Park. He wore whipcord breeches and polished riding boots, a Windsor tie and an officer’s jacket. He fed the deer flapjacks from his window in the mornings, paid $10 a year in ground rent and denounced consumerism at every turn. “Lord, how I pity a man with a steady job,” he wrote in his diary in 1941.

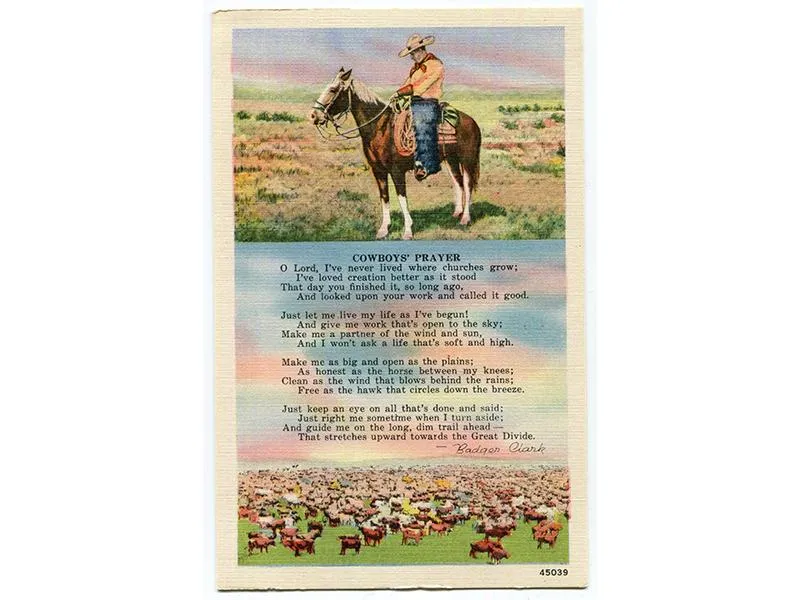

Born January 1, 1883, Badger Clark built a career writing what many today call “cowboy poetry,” and what many others, then and now, call doggerel. Clark himself seemed resigned to this lowbrow status. “I might as well give up trying to be an intellectual and stick to the naivete of the old cowboy stuff,” he wrote in his diary at the age of 58. Yet Clark’s poetry became so widely recited throughout the American West that he eventually collected over 40 different postcards featuring his most popular poem, “A Cowboy’s Prayer,” each of which attributed the poem to “Author unknown” or “Anonymous,” as if the poem belonged to everyone—as if it had been reaped from the soil itself. As Poetry magazine acknowledged in a correction in September 1917, after mistakenly attributing another Clark poem to “Author Unknown”: “It is not everyone who wakes to find himself a folk-poet, and that in less than a generation.”

Beyond his home state of South Dakota, few will recognize the name Badger Clark today. Even in the late 1960s and ’70s, when at least one of his poems slipped into the canon of the Greenwich Village folk scene, his name carried little currency. Yet at the peak of his career, Clark lunched with President Calvin Coolidge and later ushered Dwight Eisenhower through Custer State Park, where he often served as a golden-tongued ambassador.

Clark’s life and family were themselves the stuff of song: His mother was “a sturdy advocate for women’s suffrage,” Clark wrote. His father had preached at Calamity Jane’s funeral. And when Clark was just 20 years old, he scrapped college to join a group of South Dakotans set on colonizing Cuba. Their enterprise quickly folded, but Clark stayed for over a year. He found work on a plantation, narrowly survived a gunfight with the neighbors and then spent two weeks in a squalid prison singing dismal songs with an illiterate Texas cowpuncher. In a letter to his parents shortly after leaving the island, he scrawled a hasty poem:

The Parthenon’s fair, the Alhambra will do,

And the Pyramids may serve a turn,

But I took in the loveliest sight of my life

When I saw Cuba—over the stern.

While Clark is most closely associated with South Dakota, it was the borderland of southern Arizona that sparked his literary career. Like his mother and brother before him, both of whom had died before he graduated from high school, Clark contracted tuberculosis. Following a doctor’s recommendation, he retreated at age 23 from Deadwood, South Dakota, to the Arizona desert outside Tombstone. Not long after he arrived, he met brothers Harry and Verne Kendall, the new proprietors of the Cross I Quarter Circle Ranch, ten miles east of the city. They were looking for a caretaker while they worked the mines, and though the gig didn’t come with a salary, Clark could live free on the ranch, seven miles from the nearest neighbor—hardly the worst arrangement for a 23-year-old nature-lover with a communicable disease. He accepted, and for the next four years reveled in his new surroundings while his symptoms faded in the desert sun.

“The world of clocks and insurance and options and adding machines was far away, and I felt an Olympian condescension as I thought of the unhappy wrigglers who inhabited it,” he wrote of his years on the ranch. “I was in a position to flout its standards.”

Clark befriended a neighboring cowboy and welcomed others who occasionally stopped by to water their horses. Though never quite a cowboy himself—“I drearily acknowledge that I was no buckaroo worthy of the name”—he eagerly absorbed their stories, adopted their lingo and accompanied them on cattle roundups and other adventures. And when he wrote his father and stepmother back home, the ranch dog snoring at his feet and the agave towering outside his window, he occasionally turned to verse, memorializing this Western brand of freedom. His stepmother was so keen on his first dispatch, a poem called “In Arizony,” she sent it to the editors of Pacific Monthly, one of her favorite magazines. They changed the title to “Ridin,’” and several weeks later, Clark received a check in the mail for $10, spurring him to develop a literary talent that, as an editor later wrote, “tied the West to the universe.”

After four years in Arizona, Clark returned to South Dakota in 1910 to take care of his aging father in Hot Springs, and in 1915, with a loan from his stepmother, he published his first collection, Sun and Saddle Leather, later enshrined as a classic of the genre. He was able to pay her back within the year; by 1942, the book had sold more than 30,000 copies. When the Federal Writers’ Project polled the state’s newspaper editors and librarians in 1941, they ranked the collection as the best book by a South Dakota writer. To this day—thanks in part to the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, which has reissued all of Clark’s major works—it has never slipped out of print.

Inspired by Rudyard Kipling and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Clark shunned free verse in favor of meter and rhyme, composing primarily in ballad form. The best of his poems bounce you in the saddle, gallop across the page, train your eyes toward the sun and your heart toward the West, offering a vital escape from the hassles of modern life: the overdue bills, the overflowing inbox, the wearisome commute. And today, as climate change and urbanization threaten our last truly wild spaces, and Covid-19 bullies us into quarantine, that hint of freedom tastes especially sweet. Clark’s verses beg for recitation, and it’s little wonder his work spread so quickly throughout the Western cattle country of the early-to-mid-20th century. As one old cowpuncher supposedly said after reading Clark’s first collection, “You can break me if there’s a dead poem in the book, I read the hull of it. Who in hell is this kid Clark, anyway? I don’t know how he knowed, but he knows.”

Clark’s total output was slim, just three volumes of poetry, one book of interconnected short stories and a smattering of essays and pamphlets, most of them first published in magazines like Pacific Monthly or Scribner’s. He preferred living to writing about it, his grandniece once observed, and chose a craft that afforded him the greatest pleasure for the least amount of work. “If they’ll pay for such stuff,” he remembered thinking upon receiving his first check, “why, here’s the job I’ve been looking for all along—no boss, no regular hours [or] responsibility.”

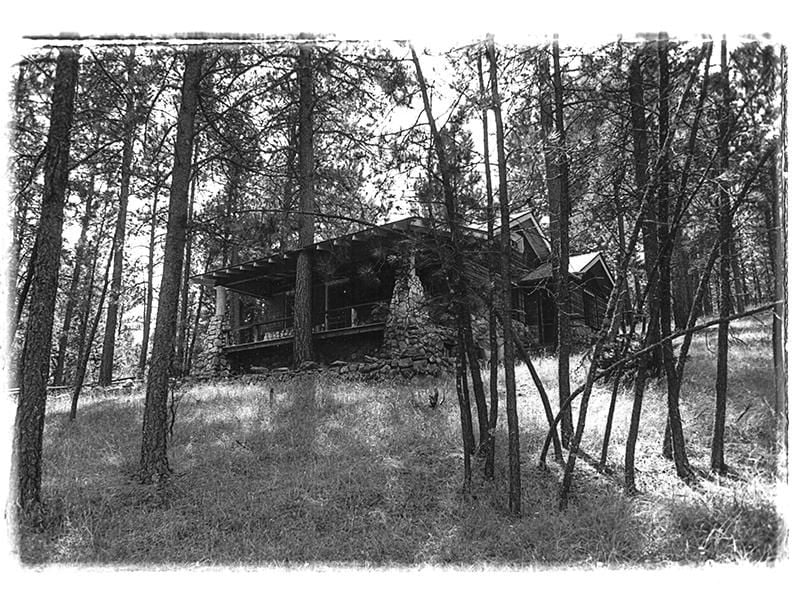

In 1924, a few years after his father died, Clark retreated to a one-room cabin in the heart of Custer State Park, and in 1937, he upgraded to a larger cabin of his own design; he called each of them “Badger Hole,” and the second one is now open to the public, largely as he left it. Clark would live there for the rest of his life, celebrating the hills in verse, rolling his own cigarettes, and consulting the wildlife for his daily weather forecast. In 1937, when South Dakota named Clark its first poet laureate, he wrote to Governor Leslie Jensen: “South Dakota, prairie and hills, has been my mother for 55 years. Some of her sons seem to love the old lady mainly for the money they can get out of her, but as I’ve never got any my affection must be the impractical, uncalculating, instinctive, genuine sort.”

In his later years, Clark spent considerable time writing letters to the Rapid City Journal, the state’s leading newspaper. They reveal a staunch pacifist, a naturalist and often brazen individualist who distrusted technology and vehemently opposed segregation. “We still owe the Negro for 250 years of unpaid labor, and we owe the Indian for some three million square miles of land,” he wrote in one letter to the paper in 1954.

While he would never become a household name, big-time musicians from Johnny Cash to Judy Collins would later perform his work. Emmylou Harris recorded songs based on Clark’s poems, as did Michael Martin Murphy, Don Edwards, Paul Clayton and Tom Russell. In 1947, killing time between trains, Clark slipped into a movie theater in Fremont, Nebraska, and was stunned to find Bing Crosby crooning Clark’s poem “A Roundup Lullaby” in the popular western musical Rhythm on the Range. The movie had come out over a decade before—Clark just didn’t know his poetry had been a part of it.

In the enthusiastic if somewhat insular community of cowboy poets, Clark remains a patron saint, his work performed at hundreds of gatherings across the country every year. “Most everybody who’s writing cowboy poetry now, who’s really serious about it—they’ve all read Badger,” says Randy Rieman, a Montana horse trainer and a mainstay on the cowboy poetry circuit. “I don’t know how you could separate today’s good writers from his work.”

Clark once bragged, “I could smoke like Popocatépetl,” referring to the famous volcano in central Mexico—but all those cigarettes would finally kill him. He died of throat and lung cancer on September 27, 1957. He was 74 years old. Acknowledging his anonymity in his later years, Clark quipped: “Mr. Anonymous has written some marvelously good things.”

The Bard's Greatest Hit

Nights when she knew where I’d ride

She would listen for my spurs,

Fling the big door open wide,

Raise them laughin’ eyes of hers

And my heart would nigh stop beatin’

When I heard her tender greetin’,

Whispered soft for me alone—

“Mi amor! mi corazón!”

1958 | Richard Dyer-Bennet

The English-born musician collected European and American folk songs, and not only performed them but sought to preserve them in his recordings. On his 1958 album, alongside such numbers as “Greensleeves” and “John Henry,” Dyer-Bennet recorded “A Border Affair” under the soon-to-be popular title “Spanish Is the Loving Tongue.”

1960 | Pete Seeger

The legendary folk singer nestled “Spanish Is the Loving Tongue” in a gentle medley of American ballads on his 1960 album The Rainbow Quest. Seeger’s plain-spoken delivery and tender picking on the banjo underline the song’s touching nostalgia for a lost lover.

1963 | Ian & Sylvia

A year before they married, the famed Canadian folk duo Ian Tyson and Sylvia Fricker recorded “Spanish Is a Loving Tongue” on their album Four Strong Winds; the lyrics’ cowboy spirit may have particularly spurred the interest of Tyson, a former rodeo rider.

1971 | Bob Dylan

The Nobel Prize winner issued “Spanish Is the Loving Tongue” as the B-side to “Watching the River Flow.” Five other versions followed, including a scintillating 1975 live performance, at the height of the singer’s fascination with the southern border.