Saluting Veterans in Film

Veterans have generally been treated with dignity and respect in Hollywood films, but there are always the exceptions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111111075018Let_There_Light_thumb.jpg)

This Veterans Day I’d like to single out some of the movies that concern members of our armed services. Not war films per se, but stories that deal with what happens to soldiers after the fighting is over.

As might be expected, the industry has taken a generally respectful attitude toward the men and women who have fought for their country. Filmmakers began turning to the Civil War as a subject when its 50th anniversary approached. Searching copyright records, film historian Eileen Bowser found 23 Civil War films in 1909; 74 in 1911; and 98 in 1913. Most of these focused on the moral choices the war demanded. For example, in The Honor of the Family, a Biograph film from 1910, a father shoots his own son to hide his cowardice on the battlefield.

Identifying performers in film as veterans became a narrative short-cut, a quick way to establish their integrity. Often veterans have been portrayed as stereotypes or caricatures, as stand-ins for filmmakers who want to address a different agenda. Actor Henry B. Walthall played Ben Cameron, “The Little Colonel,” a Civil War veteran, in D.W. Griffith’s monumental The Birth of a Nation (1915). Unfortunately, Griffith turned Walthall’s character into a racist vigilante who forms a Ku Klux Klan-like mob to attack African-Americans during the Reconstruction.

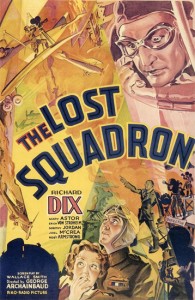

During the Depression, veterans could be seen as down-on-their-luck victims, as in Heroes for Sale (1933), where the noble Tom Holmes (played by Richard Barthelmess) suffers drug addiction and imprisonment after he is wounded in World War I. In The Lost Squadron (1932), destitute former aviators are reduced to flying dangerous stunts for an evil Hollywood director (played by Erich von Stroheim). But in The Public Enemy (1931), a gangster played by James Cagney berates his sanctimonious veteran brother, reminding him, “You didn’t get those medals by holding hands with the Germans.”

The most lauded film to examine veterans is The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), directed by William Wyler, produced by Samuel Goldwyn, written by Robert Sherwood, and starring Fredric March, Dana Andrews, and Harold Russell as three soldiers who face differing fates when they return home. While its plot can be overly schematic, the film has an honesty and courage unusual for its time—perhaps because Wyler was a veteran who experienced bombing runs while making the war documentary Memphis Belle. Russell, whose hands were amputated after a training accident, won a special Oscar for his performance.

Not all post-World War II films treated veterans so kindly. The Blue Dahlia, for example, a mystery thriller written by Raymond Chandler. In it, Navy aviator Alan Ladd returns home to an unfaithful wife who killed their son in a drunk driving accident. “A hero can get away with anything,” his wife sneers after he knocks her around. Ladd’s pal William Bendix, a brain-damaged vet with a steel plate in his head, flies into violent rages when drinking. Worried about the film’s negative portrayal of soldiers, censors forced Chandler to come up with an ending that exonerated the obvious killer. Veterans as villains show up in Crossfire (1947), a drama that also tackled anti-Semitism, and in Home of the Brave (1949), which dealt with racial issues.

More inspirational were films like Pride of the Marines (1945) and Bright Victory (1952). The former was based on the real-life Al Schmid, a Marine who was blinded at Guadalcanal, with John Garfield delivering an impassioned performance as someone unable to come to grips with his infirmity. In the latter, Arthur Kennedy plays another soldier blinded in battle. Kennedy’s vet is flawed, with bigoted racial attitudes and uncontrolled hostility towards those trying to help him. Quietly yet convincingly, the film builds considerable power as Kennedy learns to accept his limitations. Marlon Brando made his film debut as a World War II lieutenant who becomes a paraplegic after being wounded in battle in The Men (1950), directed by Fred Zinnemann and written by the soon-to-be-blacklisted Carl Foreman. The Manchurian Candidate (1962) developed an intricate conspiracy plot around Korean War veterans who were brainwashed while prisoners.

I don’t have time or space here to discuss the more recent conflicts in Vietnam and Iraq. Their films range from sentimental (Coming Home) to morbid (The Deer Hunter), with the Oscar-winning The Hurt Locker managing to hit both extremes. Not to mention the industry’s most profitable film veteran, John Rambo, played by Sylvester Stallone in four films between 1982 and 2008. All deserve further discussion in another posting.

But I would like to bring up two documentaries that have been selected to the National Film Registry. Heroes All (1919), a fundraising film for the Red Cross, was set in the newly opened Walter Reed Hospital (the renamed Walter Reed National Military Medical Center shut down at this location and moved to Bethesda, Maryland in August). It detailed efforts to rehabilitate wounded veterans through surgery and physical therapy, but also through vocational classes and recreation. Heroes All had to balance the soldiers’ pessimistic past with an optimistic future, as well as detail both a need and a solution—a reason to give money and proof that the money would help. Its narrative structure and choice of shots became models for later documentaries.

Like Let There Be Light, completed in 1946 and directed by John Huston. It was shot at the Army’s Mason General Hospital in Brentwood, Long Island, where soldiers received treatment for psychological problems. A member of the Army at the time, Huston was given specific instructions about what he was calling The Returning Psychoneurotics. Huston was to show that there were few psychoneurotics in the armed services; that their symptoms weren’t as exaggerated as had been reported; and that someone might be considered psychoneurotic in the Army, but a “success” as a civilian.

Instead, the director provided a very detailed look at how Army doctors treated soldiers with psychological issues. Like Heroes All, Huston showed private and group therapy sessions, vocational classes, and recreation. He also filmed doctors treating patients through sodium amytol injections and hypnosis. (Huston found electroshock treatments too troubling to work into the movie.) When the War Department saw the completed film, it refused to allow its release. It took until 1981 before the public was allowed to see Let There Be Light. Despite its flaws, it remains one of the most sympathetic films to deal with veterans.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)