The Prolific Illustrator Behind Kewpies Used Her Cartoons for Women’s Rights

Rose O’Neill started a fad and became a leader of a movement

:focal(536x587:537x588)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/4a/364a861f-9f2f-43d5-810b-006b2b3ba2d0/kewpies-woman-suffrage-voting-kewpie-korner2.jpg)

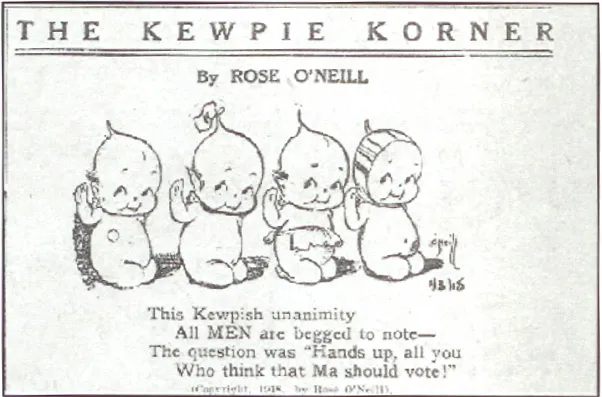

In 1914, a crowd gathered at the fairgrounds in Nashville, Tennessee. After enduring a wait in the November chill, people looked to the sky as a plane piloted by famed aviator Katherine Stinson buzzed overhead until finally, it dropped its cargo: parachuting cupid-like dolls gently floating toward the ground, wearing sashes advocating for women’s right to vote. These figurines, known as Kewpie dolls, were the brainchildren of Rose O’Neill, an illustrator who revolutionized the intertwining of marketing and political activism.

O’Neill was born in 1874 and grew up in poverty in Omaha, Nebraska. By the time she turned 8 years old, she was drawing, says Susan Scott, president of the board at the Bonniebrook Historical Society, a non-profit dedicated to educating the public about O’Neill’s life. In 1893, the O’Neills homesteaded near Branson, Missouri, at a site they named Bonniebrook.

She brought her self-taught drawing skills to New York City at 19, staying in a convent so she wasn’t all by herself in the big city, and meeting editors throughout the day at the city’s publishing offices. Much to the likely shock of the mostly men editors, O’Neill took meetings with several nuns in tow.

O’Neill eventually joined the esteemed humor magazine Puck, where she was the only woman on staff and where she drew illustrations supporting gender and racial equality. She earned a reputation as a sought-after illustrator known for fast work, drawing for magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping and Cosmopolitan, which at the time was a literary publication.

“O’Neill didn’t have any one style or method,” Scott says. “She was so versatile. That’s why the publishers loved her. It could be real cutesy and look real cute, or it could be very strong and bold and look like something a man artist would’ve drawn at the time, more masculine art.”

She often worked from Bonniebrook as the New York offices didn’t have bathrooms for women, says Linda Brewster, who has written two books on O’Neill with a third on the way. While in Bonniebrook in 1909, O’Neill would illustrate her most lasting creation: Kewpies. Adapted from the classic “cupids,” O’Neill’s smirking, cherub-like characters with rosy cheeks came about when a Ladies’ Home Journal editor asked her to create “a series of little creatures,” as O’Neill recounted in her autobiography. The editor had seen O’Neill’s drawings of cupids elsewhere and wanted something similar in the magazine.

In her autobiography, O’Neill wrote that the Kewpie is “a benevolent elf who did good deeds in a funny way.” The initial iterations of the Kewpies came with accompanying verses invented by O’Neill. “I thought about the Kewpies so much that I had a dream about them where they were all doing acrobatic pranks on the coverlet of my bed,” she wrote.

Those Kewpies leapt from her dreams onto the pages of Ladies’ Home Journal’s Christmas issue that year. Adults and children alike became enamored with the drawings. A reader, echoing a popular sentiment, wrote to Woman’s Home Companion in 1913: “Long live Rose O’Neill! She enhances the value of your magazine twenty-five per cent. Hurrah for the Kewpies and Rose O’Neill!”

Magazines clamored for a chance to publish Kewpie cartoons along with O’Neill’s stories and verses about them. Soon they emblazoned commercial products too, everything from Jell-O ads to candy to clocks. To this day, people use Kewpie Mayonnaise, a prized mayo from Japan.

Several toy factories approached O’Neill about creating a Kewpie doll, and, in 1912, toy distributor George Borgfeldt & Company started producing the dolls, with royalties going to O’Neill, made of bisque porcelain. O’Neill and her sister traveled to Germany to sculpt a few sizes of the toy and show the artists how to paint them. To her surprise, Kewpie dolls became popular – a fad no one could escape – not only in the U.S. but in Australia, Japan and places all over the world.

According to Scott, O’Neill held the trademark and copyrights to Kewpies in the U.S. and leveraged them to make an estimated $1.4 million, the equivalent to more than $35 million today.

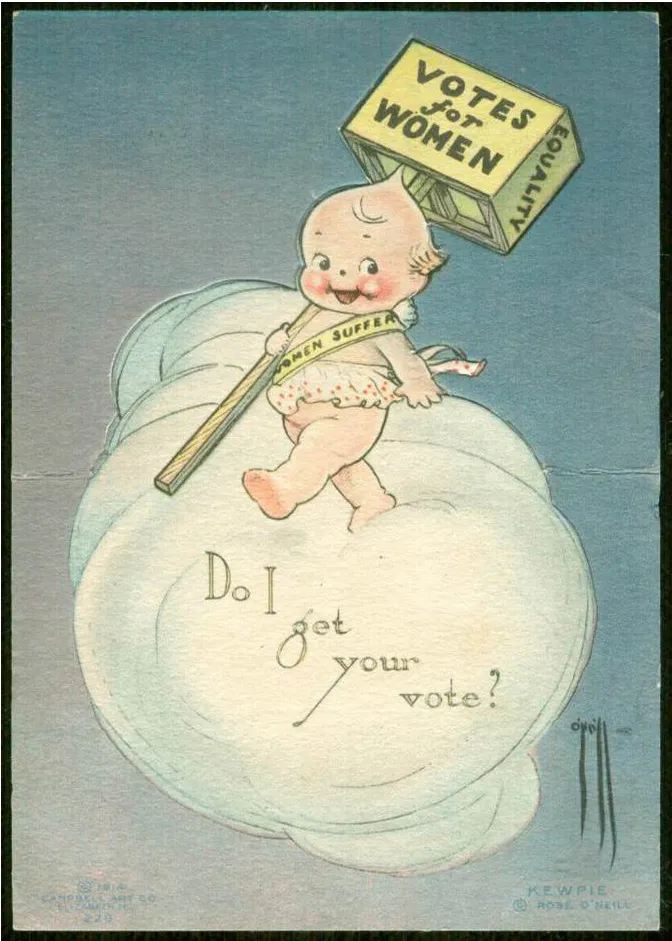

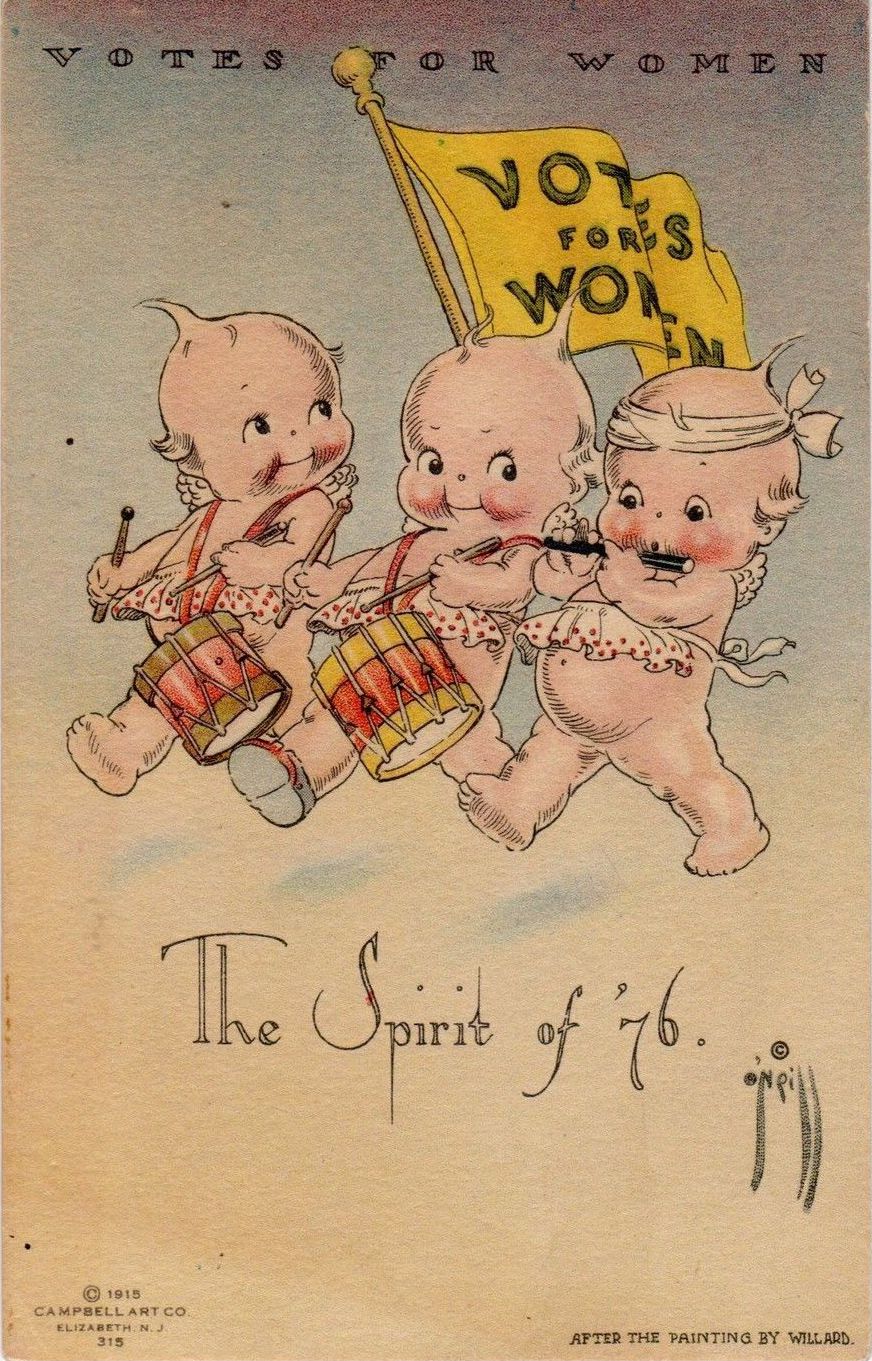

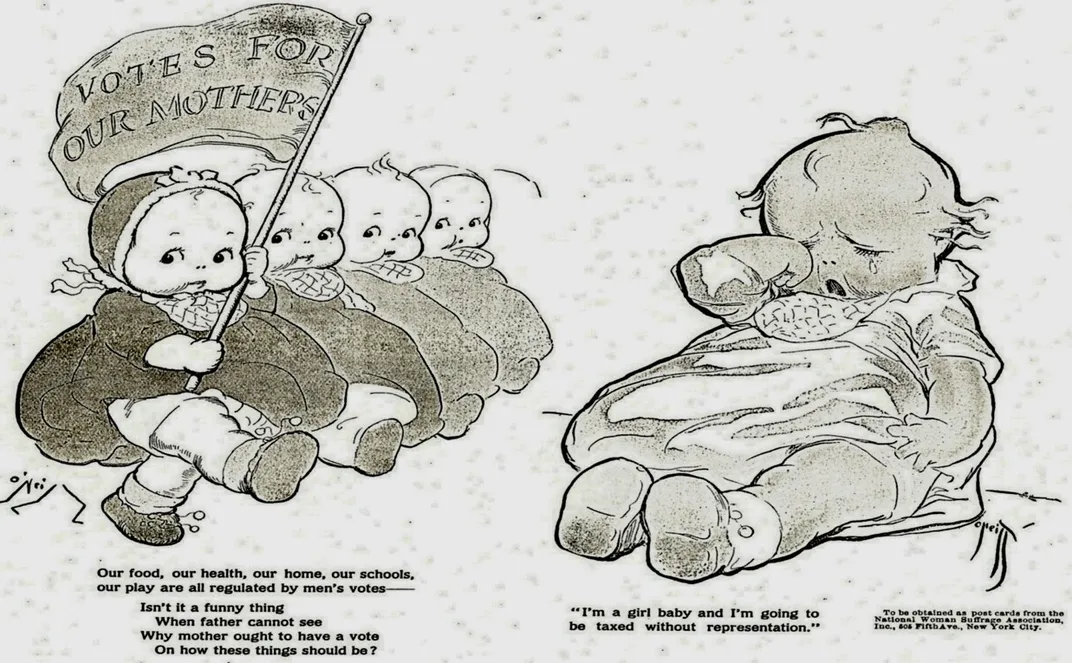

Apart from being a significant moneymaker, the Kewpies, as seen in the magazines, were cute characters with a message, often mocking elitist middle-class reformers, supporting racial equality and advocating for the poor. O’Neill also used the cartoons to champion a cause she felt passionately about: the fight for women’s right to vote.

“What was neat was that she was able to use this popular character for suffrage, and it got people’s attention,” Scott says. “Some people would go, ‘How could she use the Kewpie for suffrage? Why is she getting them involved in politics?’ And then other people just really didn’t even notice. They thought, ‘Oh, isn’t that cute? Votes for women. Oh, OK.’”

O’Neill was generous with her fortune. Brewster says she once paid for everyone in Branson to be immunized against smallpox, and she frequently gave money to artists in search of success and fans who wrote her letters.

When she wasn’t spending time at Bonniebrook, O’Neill rented a Greenwich Village apartment, becoming friends with many of New York City’s writers, poets and musicians. Being a part of this counterculture scene allowed O’Neill to participate and march in the city’s active suffrage movement. Suffragists often held banners at marches identifying their professions, so O’Neill hoisted the illustrators’ banner at marches for all to see, says Laura Prieto, professor of history and women’s and gender studies at Simmons College in Boston.

According to Prieto, it was the more-radical suffragists who added public marches to the movement. “If you think about an era in which women were supposed to be domestic creatures in the home, marching through the streets of the city is a pretty radical act,” she adds.

Kewpies played a role in these activities. There was the 1914 rally in Nashville where Kewpie dolls wearing suffrage sashes rained upon the crowd. The next year, a march in New York featured a “children’s van” decorated by O’Neill with Kewpies. Scott has found accounts of a billboard in New York that featured the Kewpies marching for women’s right to vote.

Besides lending a celebrity to the cause, Kewpies helped the suffrage movement combat the stereotype of a feminist as old, ugly and anti-men, Prieto says.

“It was a way to sell a different image of suffrage and who should support it, who already supported it, and that it was something compatible with motherhood and nurturing,” she says.

O’Neill illustrated souvenir programs distributed at marches and postcards and posters, some involving Kewpies, for the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She also contributed a Kewpie to a suffrage exhibit at a New York art gallery.

“That was her putting her creation at the service of the suffrage movement,” Prieto says.

After women won the franchise, O’Neill continued advocating for feminist causes. She showcased her art at the 1925 Exposition of Women’s Arts and Industries, designing the program cover with an illustration titled “Progress.”

Kewpies were a fad with surprising staying power, but they were still a fad. Kewpie knockoffs became more common, and people eventually lost interest in the dolls. O’Neill went on to have exhibitions of fine art illustrations – considered more serious art than Kewpies – in Paris and New York. At one point, she studied sculpture under Auguste Rodin in Paris.

By the end of her life, O’Neill’s famous generosity led her to give away most of her fortune to not only her family but artists, friends and admirers who asked for money. She died penniless in 1944.

But her influence and Kewpie dolls remain. As the 1913 letter written by the reader of Woman's Home Companion stated:

“They are equal to the best sermons, for producing a right condition of health, and good will and your readers object to them, they need a physician’s advice; yet I think there is no medicine better for them than a look at the Kewpies.”