In Search of the Real Grant Wood

The denim-clad artist who painted American Gothic wasn’t the hayseed he’d have you believe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/56/e356d11e-198e-46f2-8c7e-4e5d7ede3b73/mar2018_j12_grantwood.jpg)

I am heading north from St. Louis to Iowa City, and on the way I veer west, to visit the American Gothic House, in Eldon, a house I had heard of in a town I had never heard of. Eldon is a quiet farm town about 20 miles north of the Missouri border, full of modest foursquares and green lawns in an open landscape that stretches along the banks of the Des Moines River. Grant Wood’s inspiration, which he chanced to see when he was being driven around by a local artist in the summer of 1930, is on a slight rise above the town. What drew Wood was the upstairs front window, which reminded him of cathedral windows he had seen in France. I am surprised by how small the house is, white and crisp like a neat wooden box.

It is late October, a perfect time for this drive—the crops are in, the leaves are turning (there’s a beautiful grove of maples at the American Gothic House, more alluring to me than the house itself), the sky is high and bright. I asked the woman who runs the house what she thought was the most important thing to know about Grant Wood. She told me without hesitation that Wood was a busy craftsman as well as a painter—he did lots of interior design, sculpture, tiling and stage design. He was always engaged in multiple projects. Even though he’s best known as a painter, that wasn’t necessarily the only way he saw himself. I understand this—the effort, the thought, the putting of one part together with another part and seeing what happens, this is the driving force. How others perceive you or your work is, at least most of the time, secondary. What I realize as I travel through the landscape I once lived in, the setting of my novel A Thousand Acres and other works, is that when you are ready, you make use of what is right in front of you, because everything can be inspiring if you are curious about it.

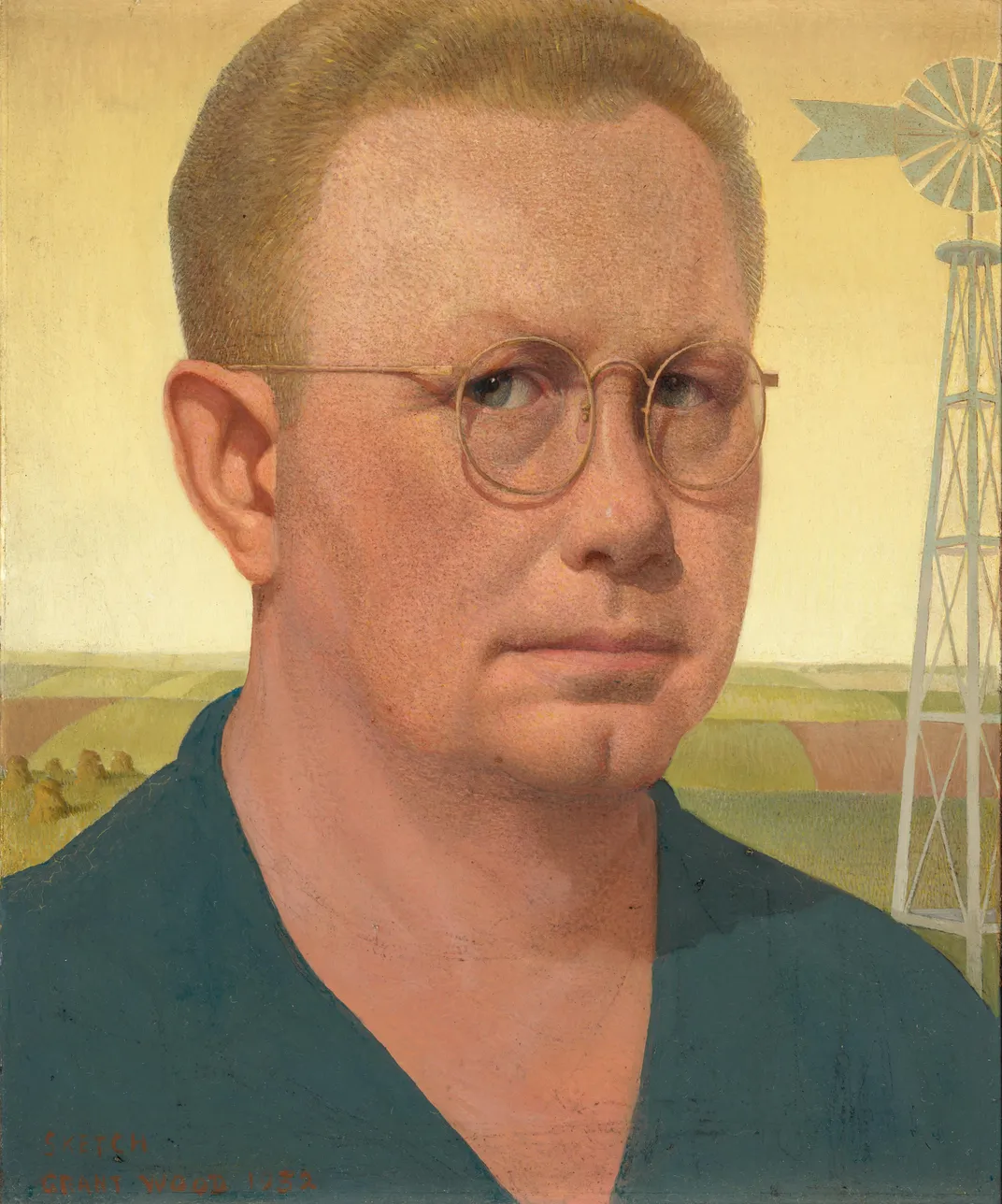

There are pictures of Wood. He always has a smile hovering around his lips and a twinkle in his eye. Let’s call that the product of the act of creating. I can also see his sense of humor in titling his painting American Gothic—his juxtaposition of the modest Eldon farmhouse with grand French cathedrals. Darrell Garwood, Wood’s first biographer, says that the window caught Wood’s eye because he thought it was “a structural absurdity.”

I explore the house a bit, and in the small gift shop buy a white hand-crocheted doily that depicts the Gothic window and neatly represents Wood’s painting as a popular and traditional icon. And then I get back in the car, drive north and turn east on Route 22.

About 30 miles out of Iowa City, I start searching for the place I found to live when I first moved to Iowa, in 1972, hoping to attend the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa. After driving back and forth and looking around, I finally turn down Birch Avenue, go a straight mile to 120th Street, turn left and head west. These roads may have names reminiscent of city streets, but they are as far out in the sticks as they could possibly be, zipping between cornfields, past barns and machine sheds, not a person to be seen.

The house we rented cost next to nothing because the property had been sold to the farmer across the road and he was planning to tear it down. As often as I could, I took walks down County Line Road toward the English River, which winds through a hilly glade. I was fascinated by the isolation and the beauty of the landscape, a different world from St. Louis, where I grew up, from the East Coast, where I went to college, and from Europe, where I traveled for a year.

It was a St. Louisan at the time, though, who gave me a reason to be appalled as well as fascinated by this place—Barry Commoner, whose book The Closing Circle I read while I was living in the farmhouse. One of his subjects was the excessive nitrates in wells, rivers and lakes caused by the use of nitrogen fertilizers—and every day I was drinking from the well at the farm-—but I also embraced (maybe because that spot in Iowa was so beautiful) his larger argument about the ecosphere. The local combination of beauty and danger, of the valley of the English River and the industrialized farming all around it, mesmerized me, and I never forgot it.

To drive through these hills is to see what must have inspired Grant Wood. The hills do look orderly, regular and almost stylized in their beauty. Wood was drawn by the small details of the hay rows on the hillside (Fall Plowing) as well as the larger perspective of the hills against the sky.

From the Depression and the 1930s, when Wood was painting his landscapes, to the 1970s, when I was living here, farming changed. Fall Plowing and, say, Appraisal, in which the item being appraised is a chicken, were no longer current—paintings in the 1970s would have been of soybean fields. I was aware of that, and because of the farming page published midweek in the Des Moines Register, I was also aware that the economics of farming had changed since the Depression, and maybe farmers themselves might have said that they had “evolved.”

Though the hills along the English River do look lost in time and almost eternal, when I pass through Wellman and then stop in Kalona, I recognize the illusion of that thought. Wellman seemed prosperous enough in 1972; it now seems moribund. Kalona, which was a center of Amish faith and horse-drawn carriages, is no longer a refuge from the modern world, but a tourist destination, with an amusing grocery store where I buy candy for the friends I will be staying with in Iowa City. The parking spaces are full of cars, and the streets are full of shoppers.

My drive north through Missouri and southern Iowa has reminded me that even though St. Louis was a fascinating place to grow up, when I got here, I had matured enough to look around and wonder about this new world, a world that no one in St. Louis (always self-important) seemed to know anything about. Iowa, in its variety and quiet, in its self-effacement and fertility, drew me in in a way that St. Louis, with its self-consciousness, did not.

I had recently been to Paris, seen the Mona Lisa and the little barrier that prevented viewers from crowding against it or touching it or stealing it. What is striking about Wood’s most famous painting is what is striking about the Mona Lisa—the simultaneous feeling the viewer has of seeing a facial expression and not knowing what that expression is intended to communicate. Yet the expressions of the farmer and his daughter in American Gothic and the expression of Mona Lisa last and last, staring at us, demanding an emotional response.

What we learn about Wood and da Vinci is that the very thing that fascinates us about their subjects was what compelled them—how could a face be painted so it would communicate complex feelings, so the viewer would understand that thoughts are passing through the mind of the subject, that the expression is about to change and has been caught just at that transitional moment? My experience, too, is that art is an exploration—when your idea triggers your interest, your job is to find your way to the product, to play with your materials until you have no more ideas, and then let the product go.

**********

Wood was born outside Anamosa, about 25 miles northeast of Cedar Rapids. The spot where Wood grew up is high and flat. The family farmhouse has been torn down, though his one-room schoolhouse is still standing, on Highway 64. It is a square white building, last in use as a school in 1959, sitting on a slight rise, now the center of a small park. Closer to town, some of the cornfields give way to stands of trees. The downtown area is brick, hearty and graceful. The Grant Wood Art Gallery is a small museum devoted to the artist’s life and times, and a gift shop, one of several stores in the red-brick main street shopping area (there is also a motorcycle museum nearby). The gallery is touristy, but soon won’t be—it is about to be renovated into a larger, more museumlike establishment. One thing that Wood’s biographers do not mention is that the Anamosa State Penitentiary is around the corner. The maximum-security facility houses 950 inmates and construction began in 1873, 18 years before Wood was born, in 1891. The penitentiary is a striking example of Gothic Revival architecture, constructed of golden limestone from the nearby quarry in Stone City (where Wood founded a short-lived artist’s colony in 1932). I imagine Grant Wood being struck by the appearance of the penitentiary and the way it fits into and also looms over Anamosa.

I can see that Anamosa-, which is on the Wapsipinicon River, in the shadows of big trees and near a state park, must have been an interesting place to grow up, full of scenic and architectural variety that an observant boy would have taken notice of. My experience is that what we see in our first decade makes strong impressions that influence us for the rest of our lives, and this is epitomized by how everything we once knew remains in our memory—the tiny yard that looked huge, the seven-step staircase to the front porch that seemed impossible to climb. We come to understand the larger picture after we move out of that small place, but there remains an eternal fascination with those locations that we knew before we gained perspective. Of the towns I’ve wandered around in Iowa, Anamosa is definitely one of the most mysterious, not what I expected.

For me, Iowa City was an easygoing town, even after I got into the Workshop. My fellow students came from all sorts of places, and when we completed our programs, most of us would scatter again. But for whatever reason—let’s call it an Iowa thing—we were not encouraged to be rivals or to compete for the attention of our teachers. We had a common goal—getting published—but we had no sense that there were only a few slots we had to vie for.

It took me almost 20 years to make use of my Iowa material. What I felt and learned percolated while I was writing books that were set elsewhere (Greenland, Manhattan) or could have been set anywhere (The Age of Grief). What I then appreciated most about Iowa was the lifestyle. This was especially true in Ames, where I taught at the state university; our house was inexpensive, the day care was across the street from the grocery store, writing fit easily into the day’s activities.

A Thousand Acres: A Novel

Ambitiously conceived and stunningly written, "A Thousand Acres" takes on themes of truth, justice, love, and pride—and reveals the beautiful yet treacherous topography of humanity.

In Ames I learned about the diversity of the Iowa landscape, in particular about the “prairie potholes” region, a large post-glacial area that dips like a giant spoon into north-central Iowa. If nitrates in an ordinary well concerned me in 1972, then their effects became more concerning where the last ice age had created huge wetlands that immigrants from eastern England had drained in the 19th century by digging wells to the aquifers. When pesticides came into general use, they, too, went straight into the aquifers. But there was also this—to drive through the landscape, especially in late winter, was to enter an eerie, flat world.

**********

Grant Wood’s early paintings, such as The Spotted Man, a male nude, and Yellow Doorway, a street scene in France, completed in 1924 and 1926 respectively, are graceful Impressionist works. But when Wood returned to Iowa, he found something in his lifelong home that Impressionist techniques could not capture. He shaved his Parisian beard, went back to wearing overalls and altered his artistic style, though the inspiration for his new style was also European, and grew out of a trip he took to Munich, Germany, in 1928 to oversee construction abroad of a stained-glass window he had designed for the Cedar Rapids Veterans’ Memorial Building. He was in Munich for three months, and when he came home, he said that he never intended to go back to Europe, though he didn’t say why. R. Tripp Evans, his most recent biographer, speculates that he was both newly inspired by the work of Flemish and German painters from the 16th century, and also put off by what the artist described as the “bohemian” culture that was even more pronounced in Munich than it was in Paris.

The Grant Wood Studio, in Cedar Rapids, is eight blocks above the Cedar River and very close to Cedar Lake, though the lake is hidden from view by Interstate 380 and lots of buildings. Wood’s studio, which he dubbed #5 Turner Alley, was given to Wood in 1924 by David Turner, the prosperous owner of a large funeral home. It had been his carriage house. Like the house in Eldon, it is surprisingly small, a place where Wood lived with his mother and (sometimes) his sister, where he designed the cabinetry for efficiency and where he also put on small dramatic productions. It is dwarfed by the huge former funeral home nearby. The upper story, where Wood lived, is white and spare, and with steep eaves. I have to stand in the middle as we are shown where he set up his easel by the window that got the best northern light. His mother’s room is tiny, and the kitchen is hardly a room. The stairs are steep—I keep my hands on both railings, going up and down.

His most important painting of 1928 was a portrait of his benefactor’s father, John B. Turner. It was thought to have been painted after Wood returned from Germany, but, Evans tells us, was discovered during the 1980s to have been painted, or at least begun, before the artist left. The style of the portrait is realist, quite distinct from his earlier Impressionist paintings, and John Turner said that he thought it unflattering. Turner, looking directly and sternly at the viewer, wearing glasses, is seated in front of maps and photographs. It is evident that Wood, recently exposed to Flemish masters, had decided to elevate gravity and realism over beauty or even attractiveness.

American Genius

Grant Wood’s art took unexpected directions, as he drew on multiple skills to create a unified vision of the world he knew. –Research by Karen Font

1890 - 1914

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/c6/bfc6bc3e-6c91-4dfd-9076-2854b6c25ddf/mar2018_j20_grantwood.jpg)

1890- Born on his family’s 80-acre farm

1910 - Joins Kalo Arts and Crafts Community House, Park Ridge, Illinois, known for its Arts and Crafts jewelry and metalwork

1914 - Produces silver tea and coffee set, c. 1914

1920 - 1924

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/f5/e3f5d801-e6b8-42bd-a33b-9d42c9d81b98/mar2018_j14_grantwood.jpg)

1920 - Embarks on the first of three visits to Europe

1924 - Paints The Spotted Man in Paris while at the Académie Julian

1925 - 1926

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/df/2edfd0a2-9656-41a5-bf1d-dcd780de9fa8/mar2018_j19_grantwood.jpg)

1925 - Creates corncob chandelier for dining room of the Hotel Montrose in Cedar Rapids

1927 - 1928

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/10/25100ab2-efb5-478d-aec5-bce6dc118e88/mar2018_j23_grantwood.jpg)

1928 - Designs stained-glass window honoring American WWI dead for the Veterans’ Memorial Building in Cedar RapidsDesigns stained-glass window honoring American WWI dead for the Veterans’ Memorial Building in Cedar Rapids

1929

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/3b/8f3ba290-1a24-4a59-99e9-838925a1a006/collage.jpg)

1929 - John B. Turner portrait wins grand prize at the Iowa State Fair, the artist’s first major recognition outside his hometown.

1929 - A portrait of his mother, Woman with Plants, is chosen for an Art Institute of Chicago show

1930

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/34/cd34101f-f2c9-4d24-96d3-547ce96827eb/mar2018_j16_grantwood.jpg)

1930 - Bucolic Stone City takes first prize at the Iowa State Fair in the landscape category

1930

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/32/8632bd0d-2e92-45bd-b746-389d21e2f5fc/mar2018_j04_grantwood.jpg)

1930 - American Gothic is accepted for an Art Institute of Chicago exhibition, where the painting is said to offer the “biggest ‘kick’ of the show”

1931 - 1932

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/b8/94b840dc-d261-49af-bd1c-819b19562f27/mar2018_j24_grantwood.jpg)

1932 - Decorates Hotel Montrose coffee shop with a mural, Fruits of Iowa, consisting of seven panels, including Boy Milking Cow

1933 - 1936

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/73/21739113-1cf8-4bd4-a19c-540edb1dd69a/mar2018_j22_grantwood.jpg)

1935 - His first solo show in NYC consists of 67 works from across his career

1936 - Spring Turning melds landscape painting with a foray into Abstractionism

1939

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/77/f57719ab-a479-4042-9b1e-e01839ab9dfb/mar2018_j25_grantwood.jpg)

1939 - Creates Sultry Night, later deemed indecent by U.S. Postal Service, which banned mailing lithographs of the work

1939

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/98/d698f622-14f4-4452-b4c5-726ab3be3946/mar2018_j21_grantwood.jpg)

1939 - In Parson Weems’ Fable, Wood renders the boy as the father of the country, with the head from Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of Washington

1941 - 1942

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/89/078998bf-5bec-4a48-b969-93f0912de3c4/mar2018_j18_grantwood.jpg)

1941 - January is “deeply rooted in my early childhood on an Iowa farm....Itis a land of plenty here which seems to rest, rather than suffer, under the cold”

1942 - Wood dies of pancreatic cancer, with his personal assistant and companion, Park Rinard, at his side

**********

I was in my late 30s when I figured out how to approach the retelling of King Lear that I had been pondering since college. What had always annoyed me about the play was that Lear never shut up, while the daughters hardly got to state their points of view. Goneril, Regan and Cordelia must have acted as they did for some reason, and I was curious about those reasons. I had lived in Iowa for 15 years by then, and while I was familiar with the landscape and felt comfortable and at home, there was still an aspect of mystery, still plenty to explore. I knew when I wrote the beginning of A Thousand Acres that the reader had to see the place, had to locate herself or himself, in order to follow the arc of my novel, and so I began with flatness. Setting is one of the most important aspects of a novel and also one of the most difficult, especially if the setting is dictating the action and the arc of the plot. The reader must see Huck on the Mississippi or Per Hansa on the South Dakota plains (as I did when I read Giants in the Earth in ninth grade) in order to understand dilemmas or plot twists.

I did plenty of research into farming and geology and history and folklore in order to give my novel as much realistic detail as I could, but I also drove around and walked around and did my best to come up with ways to describe what I saw. One of the things I realized about Iowa was the same thing that Grant Wood realized when he came back from Europe: even in Iowa we are surrounded by layers of complexity that have a lot to say about the nature of the American experiment, but they are not Hollywood things, not urban things, not fashionable things. They are about the basics of earth, weather, food, family relationships, neighbors, practicality. In a very direct way, American life rests upon and is shaped by agriculture, but most Americans overlook that except when, from time to time, someone thrusts an art object in front of them that reminds them of that fact.

Wood painted American Gothic in 1930, and it’s true that even though life in farm country had been difficult in the 1920s and the stock market had crashed, throwing the entire country into chaos, artists never know how chaos will play itself out or affect our own lives. Wood’s first idea, when he saw the house in Eldon, was to produce a pair of paintings, one exploring figures against the Gothic window in the little house, and the other situating a different couple in front of a Mission-style bungalow. When he sent American Gothic to a show at the Art Institute of Chicago, it was an instant and huge success, enigmatic and threatening (because of the pitchfork and the expressions on the figures’ faces) and representative of something inherently American that critics and the press had been overlooking through the fashionable 1900s, the war-dominated 1910s and the urbane Roaring Twenties. The arbiters of taste were ready to take up American Gothic and use it to put forward their own theories and feelings about what was happening after the crash, and what seemed about to happen in the world. “We should fear Grant Wood,” wrote no less a critic than Gertrude Stein. “Every artist and every school of artists should be afraid of him, for his devastating satire.” Wood himself never gave a definitive answer as to what he may have intended.

If Stein’s reaction seems a little hysterical, I can understand how Wood may have found the sudden celebrity flattering but disconcerting. Then again, Wood may have liked something about Iowa that I appreciated when I was there in the ’70s and ’80s: I was out of the loop. A male novelist I know once told me about going to a party in New York where he happened to be standing behind Norman Mailer. Someone bumped my friend from behind, and he stumbled into Mailer, who whipped around with his fists raised, ready to defend his status. We didn’t have that in Iowa.

A Thousand Acres made a stir, though not an American Gothic sort of stir. A novel is not a painting—its real existence is as a reader’s inner experience, idiosyncratic and private, and that remains in spite of a big prize or lots of press. American Gothic, though, hangs on a wall, inviting us to stare. A Thousand Acres, 400 pages or so, sits quietly on a shelf with scads of other books, hardly catching a reader’s eye if the reader isn’t looking for it. And then, if the reader does pick it up, the reader must decide whether or not to spend hours and hours in the world of the novel. As a result (thank goodness), when A Thousand Acres became famous, I did not have a disorienting, Grant Wood sort of experience. There were those who had read the book and loved it, those who had read the book and hated it, those who said, “Oh, I heard of that book! Didn’t it win some sort of prize?” and those who said, “What do you do for a living, then?” And when I told them, they stared at me and said, like the woman who regularly checked me out at the Fareway supermarket in Ames, “Huh.” Apart from a few denunciations that I barely noted, there wasn’t a downside to my leap to fame. This wasn’t true for Wood.

According to Evans, Wood had a secret that he wanted to keep, and the rush of his new eminence and his link in critics’ minds with major painters such as John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton put that secrecy in danger. Wood, contends Evans, was a gay man living in a Midwestern world where, unlike in Paris and Munich, homosexuality was condemned. Indeed, given Wood’s ambivalence about Paris and Munich, he may have also, at least in some ways, rejected his sexuality and dealt with it by remaining a boy—a talented, skilled, hardworking boy with a twinkle in his eye, but nevertheless a boy in overalls who could not bring himself to wholeheartedly enter the world of businessmen that he was familiar with in Cedar Rapids or the world of farm life that he knew through his demanding father. For me, Iowa meant being out of things, but when the critics embraced Regionalism in the 1930s as a form of patriotism and a rejection of European and East Coast worldliness, Wood was stuck in the spotlight. It was a lucrative spotlight, but a taxing one.

In Iowa City, I visit Wood’s house, whose current owner, Jim Hayes, is a friend of friends, and I am shown around. Hayes has worked hard to return the house to the way Wood himself left it. It is a beautiful Italianate brick building, with tall green shutters, a spacious yard and lots of trees. What strikes me are the green grids along the entrance into the back of the house, the same color as the shutters in front. I comment on them, and Hayes tells me that Wood loved order, that he composed his paintings using gridlike plans. When I look at Stone City (a hamlet nestled in rolling hills, 1930) and Near Sundown (fields in deep shadow, 1933), this is evident. He also may have melded rigor and spontaneity when he was painting in the Impressionist style. The Naked Man at first appears very orderly, but Wood overlaid the orderliness with random brushstrokes.

I relate to this, because with every novel, there is the push and pull between constructing the narrative so that it holds together and moves forward, and using a style that seems natural, or even off the cuff. When I was writing A Thousand Acres, William Shakespeare handed me the structure, and it was traditional—five acts, each act pushing steadily toward the climax. The difficulty was sticking to the structure in a believable way, especially as I got to know the daughters, their father, the neighbors and Jess, the returning rebel (based on the character of Edmund), handsome, amusing, full of new ideas about farming and agriculture.

My characters kept wanting to burst out of the plot—and in a novel this is a good thing. Lively characters give the plot energy as well as suspense. Readers get attached to them—we don’t want the bad thing that is the climax to happen to them. When I wrote my trilogy, The Last Hundred Years (Some Luck, Early Warning, Golden Age), I began it in Iowa, also, though not in the prairie potholes setting, rather in a more variable landscape east of Ames. I structured it year by year—100 chapters of equal length that forced my characters to set out, pass through dramatic events (war and financial collapse) and normal events (harvests, holidays, weddings and funerals) in a steady, rhythmic way that intrigued me, the author, first of all, and bit by bit gained forward energy that stood in for a traditional plot.

What I see in Wood’s depictions of the Iowa landscape is the understanding of the difference between large and small. Like me, he wanted to find a way to boil the grandeur of the hills and fields down a bit, to clarify it, to set it in the space defined by the canvas, and yet evoke its grandeur. In Stone City, the right side is sunlit, the left in the shade. The tiny sprouts in the foreground parallel the mature trees in the background to the left. The buildings look clean and precise, and the living figures, a cow, a man on a horse, other figures, are tiny, enveloped in and protected by the hills. The bridge, the river—everything idyllic. Near Sundown is large and small at the same time, too. The coming sundown is not threatening, but peaceful. Expansive. Grand.

Grandeur? This is Iowa, not the Sierras! But when Wood got back from Munich, he saw that there was grandeur here, that the mysterious largeness he remembered from his first ten years in Anamosa was still there, and worth investigating.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/c7/49c763b0-5276-4ea2-ba55-dd6e87f5a02a/mar2018_j13_grantwood.jpg)

In my experience, one difference between readers and art lovers on one side, and authors and artists, on the other, is that for readers and art lovers, books and paintings are a statement, an assertion of an opinion or an expression of feeling. But for authors and artists, books and paintings are an investigation that may result in an assertion, though that assertion is always more complicated and ill-defined than it appears. After American Gothic, through the 1930s, Wood went on to Death on the Ridge Road (the moment before a fatal collision between a car and truck on a rural highway, 1935), Spring Turning (a pastoral fantasy of green fields, 1936) and Parson Weems’ Fable (a depiction of the apocryphal moment when the young George Washington chopped down the cherry tree, 1939). As Wood became a public figure, he was sometimes celebrated, sometimes reviled, sometimes analyzed, sometimes misunderstood, sometimes dismissed, always used for the critics’ or the politicians’ or the collectors’ own purposes.

When I visit the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, to explore what the Grant Wood retrospective will feature, I see studies for Dinner for Threshers from 1934. It is not, in any way, one of Wood’s more sinister paintings—it evokes the pleasures of connecting and working together, the peace of a successful harvest. In the early 1930s, there were failed harvests in Iowa, because of drought and dust storms. But the number “1892” appears under the peak of the barn, indicating that the painting isn’t about the current crisis, but about something Wood remembers from his childhood on the farm. What I also notice are the four horses—the two calm plow horses beside the barn, and the picture-in-a-picture of two horses on the wall behind the farmers, also one dark, one white, tails lifted, galloping up a hill. And, the wallpaper in the dining room is ornate, gridlike, perfect. Yes, Grant Wood loved detail.

When I look at photos of him, I see in the twinkle his perception that he cannot be understood, and, in fact, he doesn’t really care. The work is the thing.

I also see this in some of his portraits, especially those of authority figures, such as Daughters of Revolution (1932), in which the female figures look straight at the viewer, one with teacup in hand, a dark, dimly realized depiction of events of the American Revolution in the background. The three women are trying to be serious, even severe, but I see a vulnerability in their carefully chosen clothing and consciously composed facial expressions. I don’t laugh at them, but I am not intimidated, either. Perhaps in portraying them, Wood was reflecting on the complexity of his relationship to his mother and his sister, who lived with him and kept him organized, but who also had opinions about his life and activities that might not have meshed with his sense of himself.

His sister, Nan, is the more ambiguous, in part because American Gothic has been misinterpreted—intended to be the farmer’s daughter, she has often been mistaken for his wife. And the farmer carries the pitchfork, but the daughter’s expression seems to indicate she is in charge. Everything about Wood’s paintings reminds me that we, the viewers, are lucky that he had such a complex personality.

**********

East Court Street, where the Wood house is located in Iowa City, was once the road to the Mississippi River. The original owner and builder of the house owned a brickworks, also on East Court Street, toward the eastern edge of town. The house he built was a self-indulgence—large rooms, beautiful bricks, sophisticated style. I am struck by how East Court Street replicates the history of housing in the 20th century. Classic styles give way to foursquares and mid-century-modern one-stories. And then the street comes to an end, at a cornfield. The corn has been harvested, but the stalks are still standing, tall, dry and yellow. I turn right, come to American Legion Road, turn left, looking for the spot where I lived for three years with friends and fellow students.

The old farmhouse is gone—I knew it would be—but the barn, now yellow, with a row of circular windows, was turned into condos. My Iowa City experience was happier than Wood’s, no doubt because I was young, just getting by, enjoying my friends and my literary experimentation, and very much enjoying this spot on the edge of town; there were fields to stroll around on one side and shops to walk to on the other.

Wood surely also enjoyed fixing up his new place on East Court Street, but he did not enjoy his life in Iowa City. By then, in 1935, he was married to a friend, Sara Sherman Maxon, and, according to Evans, even though they had an understanding that theirs was a marriage of convenience, the way that Wood’s wife organized their life didn’t suit Wood. Perhaps she had her own opinions (she was worldly and seven years older than he was), perhaps she was simply, for him, not his mother. Nor did he get along with his University of Iowa colleagues. (He was on the faculty in the studio art department from 1934 to 1941.) His productivity tapered off, and then he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He died on the eve of his 51st birthday, in 1942. I am sorry such a beautiful house as the one on East Court Street was not a happy one. Maybe my joy was that, like my friends, I knew I was getting out of here sooner or later, while Wood’s despair was that he thought he was stuck here, and longed, somehow, to get back to Anamosa, back to Stone City, or even back to Europe.

The Iowa of the 1930s that Wood depicts in his paintings is not a paradise, though his promoters expected it to be. Some works, like Death on the Ridge Road, are overtly sinister, not at all bucolic or idealistic. Others are ambiguous. My favorite of these is The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931), a dreamlike bird’s-eye view of the patriot galloping into an unknown future. No adult with any sense and a serious desire to explore his or her environment (natural, social and political) can depict only ideal scenes, even if he or she wants to, and I don’t think Wood wanted to. What strikes me about his art, laid out, painting after painting, is that he was restless, that he was ready to pick up any scene, any thought and see what he could do with it.

A painter as complex and observant as Grant Wood doesn’t always know what he or she is doing—is seized by what may be called inspiration but what I would call the mystery of complexity, and must create something that even he or she doesn’t understand.

Of the novels that I wrote set in Iowa, The Last Hundred Years trilogy is for me the most congenial. I came to feel that I was sitting quietly off to the side while my characters were chatting and getting on with their lives. I was sorry to see them go. I did not feel the same way about Larry, Ginny, Rose, Caroline. Their experiences in A Thousand Acres made them too wary, too angry. I might have liked Ginny, but she didn’t have a sense of humor, and why would she? She was a character in a tragedy.

Iowa is a special place. I am not going to make the case that it is a uniquely special place, because when I look up the hillside above the house in California I’ve lived in for the last 18 years, through the valley oaks to the weeds and the glinting blue sky, I see that every place, if you look closely, is special. Nevertheless, what Iowa promotes about itself is its decency, its hard work, its sanity.

Grant Wood saw that, but aslant, the way people who have grown up in the place they depict see contradictions, beauty, comfort and discomfort. That wasn’t my privilege when I embraced Iowa. My privilege was starting with ignorance, moving on to curiosity, then to (some) knowledge.

I drive through a small section of Iowa—Keokuk to Eldon to Ottumwa to What Cheer to Kalona to University Heights (175 miles), from there to Cedar Rapids, Anamosa, Stone City (another 56 miles) in late fall, after the harvest. The landscape is empty of humans, like many of Wood’s paintings. Every square mile invites contemplation, depiction, because it is beautiful and enigmatic.

For an artist or a writer, it almost doesn’t matter what draws you in, only that you are drawn in, that a scene evokes an inner experience that you must communicate. The frustration and the prod are that you can never quite communicate what you feel, have felt, even to yourself, and so you try again. Wood’s orderliness and his precision enabled him to boil down this feeling, to put it wordlessly on canvas. Lucky for us, it is still there, and we gaze at it.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.