The Secret History of the Girl Detective

Long before Nancy Drew, avid readers picked up tales of young women solving mysteries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/ff/2fff8de8-44c6-494d-8aed-a856fe4ce626/marylouiselibertygirls-web-resize.jpg)

“There is little excuse for giving namby-pamby books to girls.”

Those words came from an article titled “What Children Want,” published in the Chicago Evening Post in 1902. Their author, L. Frank Baum, had proven he knew what he was talking about when he published the wildly successful The Wonderful Wizard of Oz two years earlier. And a decade later, when his young, female detectives were yet another success, his values became even clearer.

In this period between the Civil War and First World War, literature began to reflect the changing norms around girls’ ambitions and women’s work. Progressive reforms led to an increase in colleges for women and coeducation; by the turn of the century, even an Ivy League school, Cornell, accepted women. A communications revolution, led by the inventions of radio transmission, telephone and typewriter, led to the creation of new career fields for women. In popular books, a new character type was born, one so familiar and beloved today that our cultural landscape would be unrecognizable without her: the girl detective.

From 1930 to 2003, WASPy Nancy Drew ruled supreme, sharing the stage from time to time with Judy Bolton and Cherry Ames. Wizardly Hermione Granger ascended from her 1997 debut through the following decade, and she in turn passed the baton to more recent neo-noir television heroines Veronica Mars and Jessica Jones.

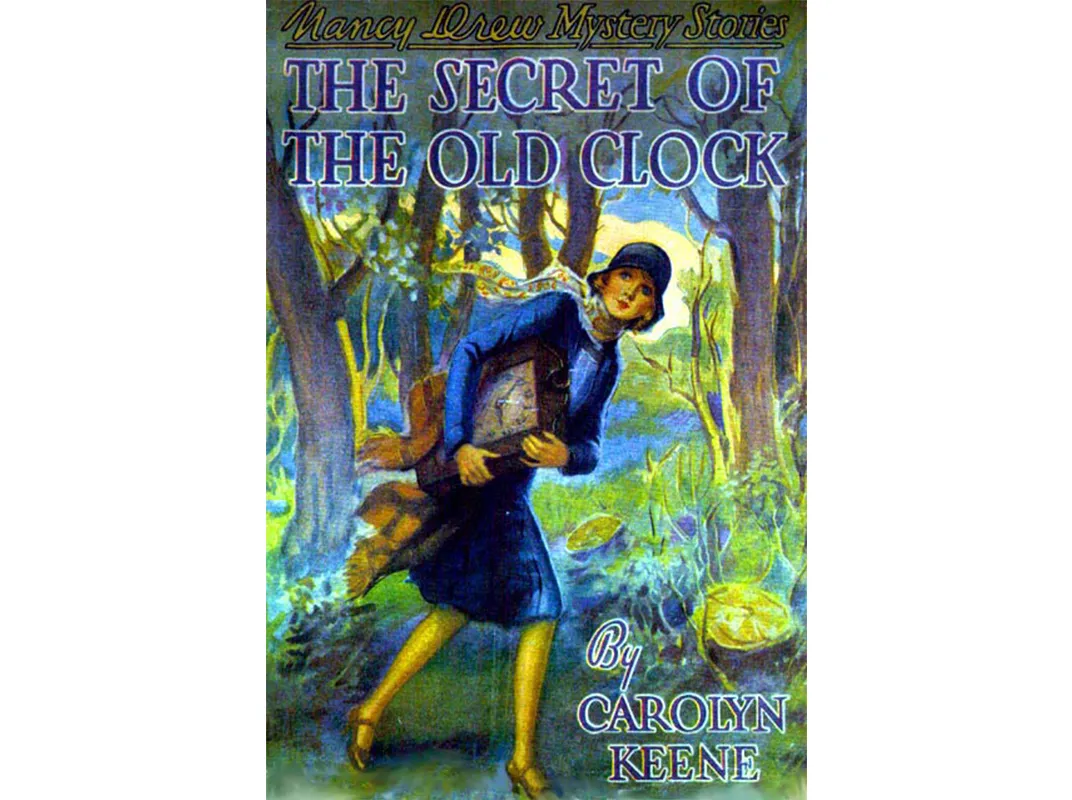

Nancy Drew has become an American icon, but she wasn’t the first of her kind. Young, female detectives existed generations before Drew was dreamed up by publisher Edward Stratemeyer and his syndicate of ghostwriters. (Carolyn Keene, the author listed on so many Nancy Drew covers, was always a pseudonym; the first Keene was 24-year-old writer Mildred Wirt Benson.) Real-life female detectives had emerged in the mid-19th century through the likes of the young widow Kate Warne, a Pinkerton Agency detective who helped smuggle Abraham Lincoln away from would-be assassins in Baltimore. On the page, meanwhile, helped along by a new fashion for teen-sleuth stories, the girl detective gradually emerged to explore a new kind of American female identity.

The surge in demand for mysteries came on the heels of a golden age of fiction for young people. Starting with Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868), the fictionalized story of her own youth, and Mark Twain’s boy-hero adventures in Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), an audience grew for picaresque, message-laden tales for impressionable minds. Toward the end of the 19th century, a thriving publishing industry meant editors vied for the most addictive stories. Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), published in America five days after its British debut, was an immediate sensation. Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet (1887) introduced Sherlock Holmes to the world; six years later, when Conan Doyle killed off Holmes and nemesis Professor Moriarty so he’d finally have time to write historical novels, readers protested. Acceding to demand in both England and America, Holmes reappeared in The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1901.

Perhaps the first true girl detective made her debut in The Golden Slipper and Other Problems for Violet Strange (1915). The author, Anna Katharine Green, was an American friend of Conan Doyle’s, and had a string of best-sellers featuring female detectives. One of the major selling points of those books was that Green known for fact-checking every legal detail in her bestselling mysteries. Green created the first truly famous female sleuth in fiction, curious spinster Amelia Butterworth, in The Affair Next Door (1897), sketching the original pattern for Agatha Christie's Miss Marple.

But her new, younger heroine, Violet Strange, is a well-off young lady whose father supports her, unaware that she likes to dabble in detective work. She solves the occasional case out of curiosity and for the novelty of earning a little money separately from her father, making sure to only accept those puzzles that “engage my powers without depressing my spirits.”

The following year, L. Frank Baum published his first girl-detective story under the pseudonym Edith Van Dyne. Baum was already famous: his books about Oz, including the 13 sequels he wrote, attained the status of a canonical American folktale. But he had never learned to manage his money. His wife, Maud Gage Baum, had had to draw from her inheritance to buy Ozcot, their home in the Hollywood hills. Within a decade after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum, a dreamer and devoted gardener, was broke.

Baum had been tinkering with the idea of a mystery series for nearly five years, and in 1911, there was a false start with The Daring Twins, intended to be the first in an Oz-like series written under his own name. The sequel, Phoebe Daring, appeared the next year, and then the series was quietly discontinued; the Daring characters, tellingly, were wrapped up in their own financial anxieties, dismaying publishers and readers alike. As Edith Van Dyne, Baum embarked on a fresh effort, Mary Louise, naming his orphaned heroine after one of his sisters. He was likely drafting the story in 1915, when Green’s Violet Strange made her debut. But Baum’s publishers were wary: they declined the first version, judging the character of Mary Louise too unruly.

By then, women’s rights were pressingly in the news, though women did not gain the vote nationally until 1920. The “Woman Question” was not a question in Baum’s household, at least. Matilda Joslyn Gage, one of the most remarkable voices for women’s suffrage and minority rights in late 19th-century America, was his mother-in-law. Her epitaph reads, “There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven; that word is Liberty.”

Baum quickly rewrote Mary Louise and saw it published in 1916. Eventually, the new series would have ten books, half of them ghostwritten, and collectively they became known as “The Bluebird Books” for their powder-blue cloth bindings. The stories start with the acknowledgment that the shadow of World War I changed gender norms irrevocably. Baum deftly frames this in Mary Louise and the Liberty Girls: in the words of a grandfatherly character, “‘This war,’ remarked the old soldier, thoughtfully, ‘is bringing the women of all nations into marked prominence, for it is undeniable that their fervid patriotism outranks that of the men. But you are mere girls, and I marvel at your sagacity and devotion, heretofore unsuspected.’”

Once Mary Louise was received to kind reviews and healthy sales, Baum introduced a new character who eventually took over as the heroine of the series. Josie O’Gorman is at first the cheery, stocky, freckled, “unattractive” yet essential counterpart to Mary Louise, who has enviable dresses and “charming” manners. Josie, the daughter of a secret agent, has none of the strident moral righteousness that makes Mary Louise just slightly tiresome. She is quiet, irreverent and ingenious; it is she who the reader is glad to find again in each sequel.

The old is about to become new again; earlier this year, CBS announced the development of a new Nancy Drew television series, one where the heroine, an NYPD detective in her 30s, is played by Iranian-Spanish-American actress Sarah Shahi.

In the century since she first materialized, the appeal of the girl detective has grown from cultish to mainstream, with reliably recurring tropes of her own. She oscillates between tomboyishness and a feminine ideal. She has been through something terrible – often she is an orphan – that gives her an understanding of darkness and loss. She operates in a volatile world where consensus seems to be crumbling on the edges. Ultimately, as an unquestioning agent of the law, her aim is to smooth those edges as far as she can.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/headshot22_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/headshot22_copy.jpg)