Secretary Clough on Jefferson’s Bible

The head of the Smithsonian Institution details the efforts American History Museum conservators took to repair the artifact

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Jefferson-Bible-631.jpg)

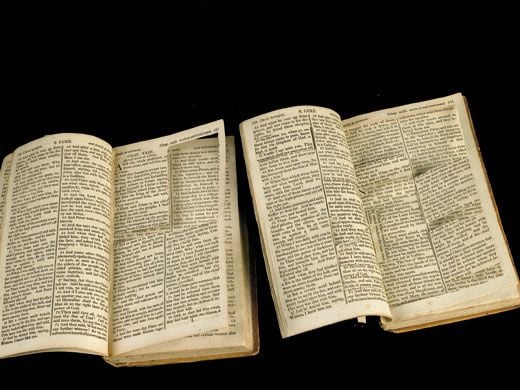

At age 77, Thomas Jefferson, after two terms as president, turned to a project that had occupied his mind for at least two decades—the creation of a book of moral lessons drawn from the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, Mark and John. With painstaking precision, Jefferson cut verses from editions of the New Testament in English, French, Greek and Latin. He pasted these onto loose blank pages, which were then bound to make a book. He titled his volume The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth; it has become known as the Jefferson Bible. Because Jefferson found this project intensely personal and private, he acknowledged the book’s existence only to a few friends, saying that he read it before retiring at night.

Thanks to the research and efforts of Cyrus Adler, librarian of the Smithsonian Institution from 1892 to 1909, we were able to purchase the Jefferson Bible from Jefferson’s great-granddaughter Carolina Randolph, in 1895. In 2009 a preservation team led by Janice Stagnitto Ellis, paper conservator at the National Museum of American History (NMAH), discovered that the book’s binding was damaging its fragile pages; to save them she temporarily removed it. Earlier this year, I visited the conservation lab at the NMAH to see the fruit of the yearlong conservation treatment. Having bought a copy of the Jefferson Bible some 40 years ago, I was especially fascinated as Ellis showed me the original loose folios with cutouts pasted on by Jefferson himself.

With the help of museum staff and the Museum Conservation Institute, the conserved Jefferson Bible will be unveiled in an exhibition (November 11-May 28, 2012) at NMAH’s Albert H. Small Documents Gallery. The exhibition will tell the story of the Jefferson Bible and explain how it offers insights into Jefferson’s ever-enigmatic mind. Visitors will see the newly conserved volume, two of the New Testament volumes from which Jefferson cut passages and a copy of the 1904 edition of the Jefferson Bible requested by Congress, with an introduction by Adler. This Congressional request began a nearly 50-year tradition of giving copies to new senators. The exhibition will be accompanied by an online version. Smithsonian Books will release the first full-color facsimile of the Jefferson Bible on November 1, and the Smithsonian Channel will air a documentary, “Jefferson’s Secret Bible,” in February 2012. For more information and to purchase a copy of the facsimile, please visit Americanhistory.si.edu/jeffersonbible.

Jefferson’s views on religion were complex, and he was reluctant to express them publicly. “I not only write nothing on religion,” Jefferson once told a friend, “but rarely permit myself to speak on it.” Now, nearly two centuries after he completed it, the Smithsonian Institution is sharing Jefferson’s unique, handmade book with America and the world.

G. Wayne Clough is Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)