‘Shaft,’ ‘Super Fly’ and the Birth of Blaxploitation

In this excerpt from ‘Music Is History,’ the drummer for the Roots and all-around music ambassador looks at a year when everything changed

:focal(2082x1408:2083x1409)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/20/fb/20fbb24a-e155-48e7-bf7e-e87a60d33a1b/shaft-studio-shot.jpg)

Culture shines a light on the world around it.

In our lifetime, some years seem absolutely packed with events. The year 2020 was one of those, and when people try to compare it to anything, they compare it to 1968. Those are the newsiest years, but they’re not the longest. The longest year in history was 1972. It was already longer than the years around it because it was a leap year. Time didn’t fly. But it did Super Fly.

On August 4 of that year, Super Fly, starring Ron O’Neal as the Harlem drug dealer Youngblood Priest, appeared in theaters. Today we think of Super Fly as a blaxploitation classic. Back then, as the genre was being born, it was just a movie following on the heels of other movies. That’s another thing about history. Categories get created after events, and those events are retroactively loaded into those categories.

To understand the category around Super Fly, you have to go back a year, to another movie, Shaft. Shaft was the Big Bang of Black movies. Before that, of course, there were other Black directors. There was Oscar Michaux. There was Spencer Williams. There was the experimental director William Greaves (Symbiopsychotaxiplasm), and the versatile and surprisingly commercial indie director Melvin Van Peebles (Watermelon Man, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song).

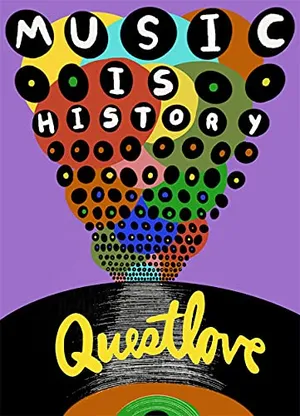

Music Is History

Music Is History combines Questlove’s deep musical expertise with his curiosity about history, examining America over the past fifty years.

And then there was Shaft. Gordon Parks, who directed the movie, was already a Black Renaissance man: a pioneering photographer, an author and a filmmaker. Shaft was based on a detective novel by a man named Ernest Tidyman, who turned it into a screenplay with a man named John D. F. Black. Black was white, as was Tidyman, as was the Shaft in Tidyman’s novel. Onscreen, though, Shaft turned Black, in the person of Richard Roundtree, whose co-stars included Moses Gunn, a classically trained actor with perhaps the coolest name in history, and Camille Yarbrough, a performance poet and stage actress, the sultry voice that holds the word “Shouuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuld” for 30 seconds in Fatboy Slim’s “Praise You.”

The movie was an undeniable hit. Theaters in New York showed it around the clock (“Shaft! 24 Hours a Day!” said the ads—sounds exhausting).

And then there was the soundtrack. Isaac Hayes had been one of the staples of the Memphis-based Stax label for a decade: a session player, a producer and (with his partner, David Porter) a songwriter. Toward the late ’60s, the label went through changes. Otis Redding died in a plane crash. Atlantic took control of Stax. Hayes reemerged as a performer. He was the label’s savior, and he looked like one, with his big bald head, his big gold chains and his big dark sunglasses. Hayes was actually considered for the lead role in Shaft, but instead he got the soundtrack gig. Based on the dailies Parks was supplying, he wrote a number of compositions, including a song called “Soulsville” and an instrumental called “Ellie’s Love Theme.” The third piece was the Shaft theme.

You know it, right? Hi-hat skims along on sixteenth notes, drums played by Willie Hall. Then there’s the immortal wah-wah guitar played by Charles “Skip” Pitts, who only a year or so before had played an equally immortal part on the Isley Brothers’ “It’s Your Thing.” Then the rest of the band, flute, horns, piano. It takes almost three minutes for any vocals, and they’re more spoken than sung. The lyrics mostly just describe Shaft. Above all, he’s a bad mother . . . well, you know.

The album stayed on the charts for more than a year and became the bestselling release in Stax history. It was the first double album by a soul artist, and Hayes won four Grammys for it and was nominated for two Oscars. He won Best Original Song for the title track, the first Black composer to do so. Shaft was so big that it had sequels. Two, in fact, one where Shaft had a big score (Shaft’s Big Score—Hayes was busy so Parks did the music himself, but in a “What Would Hayes Do?” spirit—the cues are so derivative), the other where Shaft went to Africa (Shaft in Africa—music by Johnny Pate, including a loop that Jay-Z later used on “Show Me What You Got” to usher in the “gospel chops” wave).

Super Fly was not a sequel, though it was in a sense a direct descendant of Shaft—it was directed by Gordon Parks, Jr. It was a qualified hit. O’Neal was mainly a stage actor, but people took exception to the Youngblood Priest role. Especially Black people. Junius Griffin, who ran the Hollywood branch of the NAACP—there’s a job—worried that it was glorifying violence, drug use and a life of crime. He didn’t just worry. He spoke out against it: “We must insist that our children are not exposed to a steady diet of so-called black movies that glorify black males as pimps, dope pushers, gangsters, and super males.” The organization, along with Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), tried to keep it from reaching theaters, or to pull it out of the theaters it had already reached. Other organizations argued that it was, if not an overt tool of white control, a perfect example of the way that the white hegemony had forced Black people to internalize stereotypical ideas of themselves. Rick Ross—not the rapper, who was born William Leonard Roberts, but the guy he took his stage name from, the legendary California drug trafficker “Freeway” Rick Ross—has said that he was motivated to take up a life of crime specifically because of Super Fly. There is a fascinating discussion here about the influence of culture on society, about the seductive power of negative role models and the way that they can fill a vacuum that isn’t otherwise occupied by positive options. I want to focus that discussion by speaking not about the movie, but about the soundtrack.

Recorded by Curtis Mayfield as his third solo studio album, Super Fly was, from the looks of the album cover, a collision of messages. The left side, apart from Curtis’s name at the top, is given over entirely to the movie—to the hand-lettered red-and-yellow logo of the title and a photo of Ron O’Neal, the star of the film, gun in hand, standing over a barely clothed woman. The right side of the cover is all Curtis, his face hovering thoughtfully like a moon. That’s the tension of the cover, and of the album: Would it continue that “steady diet” of “pimps, dope pushers, gangsters, and super males,” or would it reflect Mayfield’s history of incisive social commentary, mixing uplifting messages of justice and Black empowerment with warnings about what might happen if those messages weren’t heeded? Would the artist be able to salvage ethical content from a movie that seemed at times unwilling to control its message?

It was a battle, and from the first seconds of the album, Mayfield won. “Little Child Runnin’ Wild,” the opener, nods to the Temptations’ “Runaway Child, Running Wild,” released back in 1969. “Pusherman” was a lightly funky, deeply seductive portrait of a drug dealer. And then there was “Freddie’s Dead,” the album’s lead (and highest-charting) single. Freddie was a character in the movie played by Charles McGregor, a veteran Black actor and a staple of blaxploitation movies. McGregor had been in prison often as a young man, and after his release specialized in playing streetwise characters. You might also know him from Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles, where he played Charlie, the railroad worker who is sent with Bart (Cleavon Little) on a hand cart up the tracks to find some quicksand that the surveyors have reported. When the railroad bosses realize they have to figure out the extent of the quicksand situation, the crew boss suggests sending horses. The big boss smacks him on the head. “We can’t afford to lose horses, you dummy!” Who can they afford to lose? See you later, Bart and Charlie.

Brooks’s movie was both as brutal and as empathetic an act of Jewish articulation of Black pain as “Strange Fruit” (and not in a carpetbagging way—the movie was famously co-written by Richard Pryor), but it wouldn’t come out until 1974. So from the perspective of Super Fly, it didn’t yet exist. At that point, Charles McGregor was only Freddie. And while in the movie his death followed the code of the streets—he was picked up by the cops and snitched, though only after being beaten, and then was killed by a car while trying to escape—the song works wonders, converting Freddie, and his memory, into both a vessel of empathy and a cautionary tale. We discover right at the beginning that “Everybody’s misused him, ripped him up and abused him.” He’s “pushing dope for the man,” Mayfield sings, “a terrible blow” (which is also sort of a terrible pun), but also “that’s how it goes.” Matter of life and death, matter of fact. And then “Freddie’s on the corner,” or maybe “a Freddie’s on the corner,” a new one, getting ready to start the same cycle all over again.

History repeats itself, especially when people don’t remember that Freddie’s dead.

Adapted excerpt from the new book MUSIC IS HISTORY by Questlove with Ben Greenman, published by Abrams Image.

Copyright © 2021 Ahmir Khalib Thompson

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.