Sherlock Holmes and the Tools of Deduction

Sherlock Holmes’s extraordinary deductions would be impossible without the optical technologies of the 19th century

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120731013008Powell__Leaead_no-1_470.jpg)

![]()

Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Holmes and Watson (image: basilrathbone.net)

Sherlock Holmes’s extraordinary talent for deduction has been well documented by Arthur Conan Doyle. Though they often seem nearly mystical in origin, Holmes’s deductions were in fact the product of a keenly trained mind. Holmes was well-versed in forensic science before there was a forensic science to be well versed in. In his first adventure with Dr. John Watson, A Study in Scarlet, Watson himself enumerates the skills, talents, and interests in which Holmes exhibited a useful capacity. According to Watson, Holmes’s knowledge of botany is “variable”, his skill in geography is “practical but limited”, his knowledge of chemistry “profound”, and regarding human anatomy, his knowledge is “accurate.” The applied knowledge of these various sciences made “the science of deduction” possible. But you don’t have to take Watson’s word for it. Forensic scientist and Holmes scholar Dr. Robert Ing, has closely read Conan Doyle’s stories to craft a more specific list of skills that Holmes demonstrates a working knowledge of: chemistry, bloodstain identification, botany, geology, anatomy, law, cryptanalysis, fingerprinting, document examination, ballistics, psychological profiling and forensic medicine. But knowledge by itself is not enough. In order to put these skills to use to find and decipher the clues that lead to his uncanny deductions, Holmes relied on the optical technology of the time: the magnifying glass and microscope. By today’s standards (not to mention the fantastic machines used in television shows like “CSI”) these tools are not advanced, but in Victorian England they were incredibly precise and quite well made.

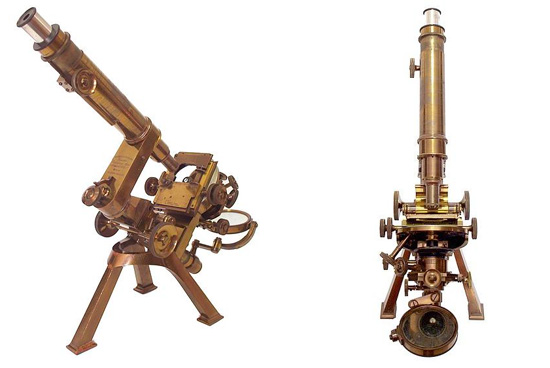

In his paper “The Art of Forensic Detection and Sherlock Holmes,” Ing deduced that when working at a micro-scale, Holmes would have most likely used a “10 power silver and chrome magnifying glass, a brass tripod base monocular optical microscope probably manufactured by Powell & Lealand.” The specific brands for these tools are never mentioned in any Holmes story, but Ing notes that these items were the most popular at the time.

Powell and Lealand No. 1 microscope (image: antique-microscopes.com)

To get more specific, the microscope Holmes likely used known as the Powell & Lealand No.1, the design of which remained almost completely unchanged for the better half of the nineteenth century. It was known for having some of the finest brass finish and workmanship of the time. The No. 1 was also quite versatile. Its pivoting arm allowed the eyepiece to be turned 360 degrees, completely away from the staging area if necessary. And the body of the microscope is constructed to allow for interchangeable eyepieces – the monoculuar piece (shown) can easily be replaced with the binocular piece or a longer monocular eyepiece, a feature that is also made possible by Powell and Lealand’s unique tube design. And of course the No. 1 also includes an ample stage and the standard macro and micro adjustments. While many microscopes were redesigned and improved over decades, the No. 1 was able to retain its original 1840s design because it was crafted to make it easy to replace parts as lens technology improved. It was a beautifully designed and well-crafted product.

In the 1901 edition of his treatise The Microscope: And Its Revelations, British physician and President of the Microscopal Society of London Dr. William Carpenter, writes that he

“has had one of these microscopes in constant, and often prolonged and continuous, use for over twenty years, and the most delicate work can be done with it to-day. It is nowhere defective, and the instrument has only once been ‘tightened up’ in some parts. Even in such small details as the springing of the sliding clips–the very best clip that can be used– the pivots of the mirror, and the carefully sprung conditions of all cylinders intended to receive apparatus, all are done with care and conscientiousness.”

Surely as diligent an investigator as Holmes would only have the most precise, most reliable microscope.

Now let us turn our attentions to the magnifying glass. The object with which Sherlock Holmes is perhaps most closely associated – and rightfully so. In fact, A Study in Scarlet was the first work of fiction to incorporate the magnifying glass as an investigative tool. In that text, Watson dutifully documents, though he does not fully understand, Holmes’s use of the magnifying glass:

As he spoke, he whipped a tape measure and a large round magnifying glass from his pocket. With these two implements he trotted noiselessly about the room, sometimes stopping, occasionally kneeling, and once lying flat upon his face….As I watched him I was irresistibly reminded of a pure-blooded well-trained foxhound as it dashes backwards and forwards through the covert, whining in its eagerness, until it comes across the lost scent….Finally, he examined with his glass the word upon the wall, going over every letter of it with the most minute exactness. This done, he appeared to be satisfied, for he replaced his tape and his glass in his pocket.

As Holmes stalks the room, Watson compares him to a bloodhound. However, the image of Holmes at work –puffing on his pipe, oblivious to the world around him as he methodically walks back and forth with a large magnifying glass– also evokes a more modern (19th-century modern) comparison: the detective as a steam-powered, crime-solving automaton with a single lens for his all-seeing eye. Indeed, in a later story, Watson calls Holmes “the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen.” In the 19th century, these optical technologies changed the way we see the world. The magnifying glass and the microscope reveal aspects of our world that are invisible to the human eye. Sherlock Holmes does the same. The magnifying glass has become so closely associated with Holmes that it is, essentially, a part of him. He internalized and applied this new technologically-assisted understanding of the world so that the optical devices of the 19th century were merely an augmentation of his natural capabilities. As an avatar for humanity’s rapidly expanding perception of the world, Sherlock Holmes was the most modern of modern men.

This is the third post in our series on Design and Sherlock Holmes. Previously, we looked at the architecture of deduction at 221b Baker Street and the history of Holmes’s iconic deerstalker hat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)