Show Time at the Apollo

A stellar roster of African-American singers, dancers and comedians got their start at the venue, celebrating its 75-year history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Show-Time-Apollo-Theater-631.jpg)

One night in April 1935, a statuesque brunette stood backstage at the Apollo Theater in New York City. Aware that the theater’s tough audience could make or break her career, she froze. A comedian named Pigmeat Markham shoved her onto the stage.

“I had a cheap white satin dress on and my knees were shaking so bad the people didn’t know whether I was going to dance or sing,” she would remember.

The ingénue was Billie Holiday.

She would perform at the Apollo two dozen times en route to becoming a music legend and one of the most influential vocalists in jazz.

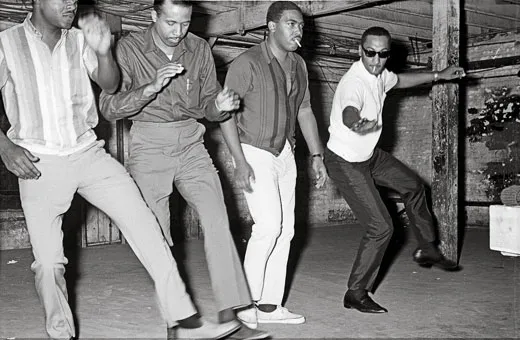

For more than 75 years, entertainers—most of them African-American—have launched their careers, competed, honed their skills and nurtured one another’s talent at the Apollo Theater. Along the way they have created innovations in music, dance and comedy that transcended race and, ultimately, transformed popular entertainment.

“You can basically trace any popular cultural form that we enjoy today back to the Apollo Theater as the place that did it first or did it best,” says Ted Fox, author of the 1983 book Showtime at the Apollo. “It is an unmatched legacy.”

The Harlem theater’s groundbreaking role in 20th-century culture is the subject of “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing,” an exhibition of photographs, recordings, movie footage and other memorabilia at Detroit’s Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History until January 2, 2011. (It then moves to the Museum of the City of New York and the California African American Museum in Los Angeles.) The exhibition was organized by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and the Apollo Theater Foundation.

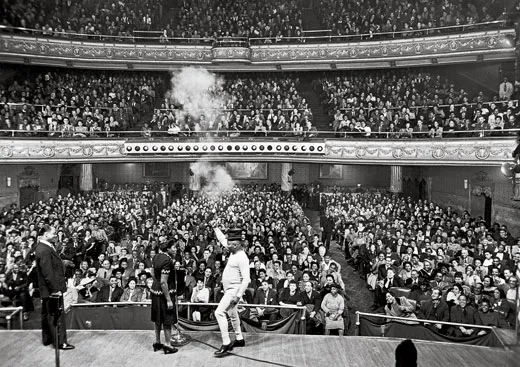

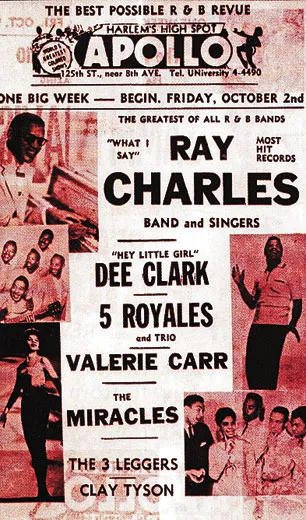

The Apollo, previously a burlesque house for whites only, opened in 1934 to racially integrated audiences. Its reputation as a stage on which performers sweat to win the affection of a notoriously critical audience and an “executioner” shoos unpopular acts away can be traced to Ralph Cooper, the actor, radio host and longtime Apollo emcee. It was he who created the amateur-night contest, a Wednesday fixture and audience favorite that aired on local radio.

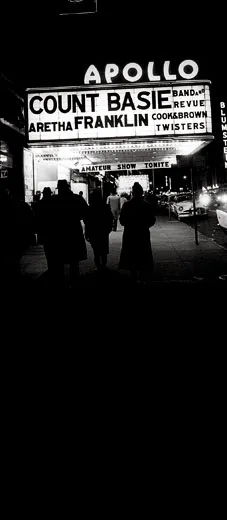

Frank Schiffman and Leo Brecher, who bought the theater in 1935, adopted a variety-show format; promoted the amateur-night contest, eventually heard on 21 radio stations; and spotlighted big bands. In May 1940, the New York Amsterdam News reported, the theater turned nearly 1,000 people away from a sold-out Count Basie show that the paper called “the greatest jam session in swing history.”

“During its first 16 years of existence, the Apollo presented almost every notable African-American jazz band, singer, dancer and comedian of the era,” co-curator Tuliza Fleming writes in the exhibition’s companion book.

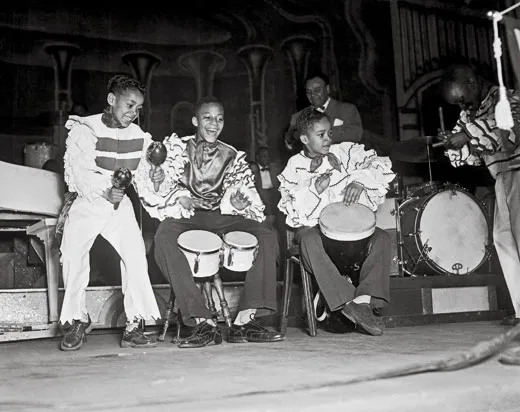

Shows featuring “Little Richard” Penniman, Chuck Berry and others in the mid-1950s helped shape rock ’n’ roll. In a 1955 performance, Bo Diddley’s rumba rhythms, driving guitar beat and swinging hips notably captivated one member of the audience: 20-year-old Elvis Presley. “That’s how Elvis got his pelvis,” Cooper recalled.

James Brown, the “Godfather of Soul,” who said he first appeared at the Apollo in 1959, became a regular there and helped pioneer soul, funk and hip-hop music. “When he sang ‘Please, Please, Please,’ we all would faint,” the singer Leslie Uggams, a frequent Apollo performer, tells Smithsonian. “Then he’d drop to his knees and put that cape over his shoulders. You could feel the theater just pulsate.”

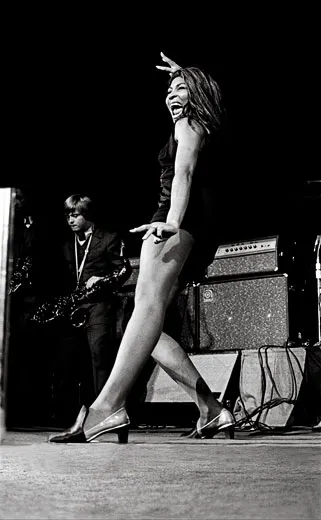

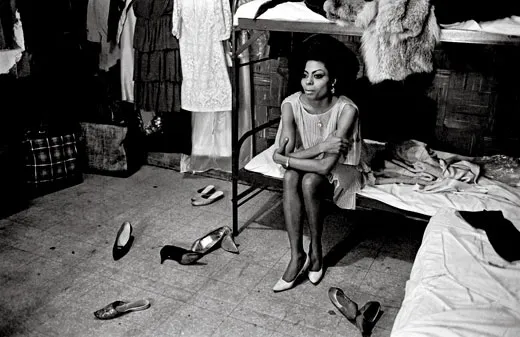

The Apollo showcased top female artists such as Aretha Franklin, the “Queen of Soul,” whose fame was so far-reaching Zulu chief Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi, future founder of South Africa’s Freedom Party, traveled to see her perform in 1971. Tina Turner, the “Queen of Rock ’n’ Roll,” says she first appeared at the Apollo in 1960 as part of the Ike and Tina Turner Revue. Wearing microscopic skirts and stiletto heels, she exuded raw sex appeal on stage long before Madonna and Beyoncé ever drew attention for risqué displays.

The theater was also a comedy laboratory. Richard Pryor, who first did stand-up there during the turbulent 1960s, used “the rage and frustrations of an era to spur his comic genius,” says NMAAHC director Lonnie Bunch. “He ripped the scab off. He symbolized a freedom that allowed [other comedians] to tap sexuality, gender issues and economic foibles.”

Hard times arrived in the mid-1970s as a local economic crisis and competition from large arenas such as Madison Square Garden thinned the Apollo’s audience. The theater shut its doors in 1976. But in the 1980s, businessman Percy Sutton’s Inner City Broadcasting Corporation bought it, renovated it, secured landmark status and revived amateur nights, which continue to sell out to this day.

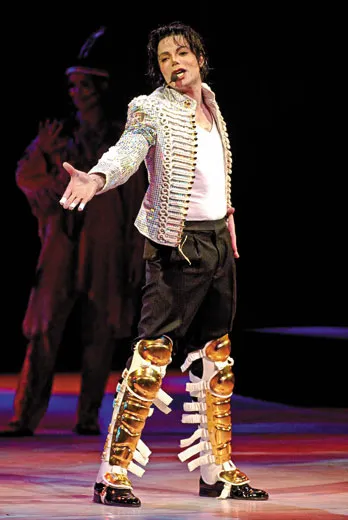

This past June, the theater’s Hall of Fame inducted Aretha Franklin and Michael Jackson, who first shot to stardom as the lead singer of the Jackson Five following the group’s 1967 amateur-night victory. Jackson’s last public performance in the United States was at a 2002 Democratic Party fund-raiser at the Apollo, where he sang his 1991 hit “Dangerous.” When a spontaneous memorial sprang up outside the theater following Jackson’s death in June 2009 at age 50, the Rev. Al Sharpton told the crowd, “He smashed the barriers of segregated music.”

Many performers found mentors at the Apollo. Smokey Robinson recalls Ray Charles writing arrangements for the songs that Robinson and his group, the Miracles, sang at their 1958 Apollo debut. “Little Anthony” Gourdine, lead singer of the Imperials, recalls singer Sam Cooke writing lyrics for the group’s hit “I’m Alright” in the theater basement.

“It was a testing ground for artists,” says Portia Maultsby, co-editor of the book African American Music. It was also, she says, “a second home, an institution within the community almost at the level of black churches.”

Lucinda Moore is an associate editor at Smithsonian.