The Simpson Family Made Its Television Debut 30 Years Ago

When they arrived on the Tracey Ullman show, their look was a little more ragged

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/f7/91f72103-18c4-48a7-b9a9-9d251abaa8bc/apr2017_h02_phenom.jpg)

When American viewers first met the Simpsons, 30 years ago this April, Homer and Marge were lovingly tucking their children into bed. “Um, Dad,” Bart asked in his first appearance. “What is the mind? Is it just a system of impulses, or is it something tangible?” “Relax,” Homer responds. “What is mind? No matter. What is matter? Nevermind.” Lisa was close to drifting off when Marge cooed, “Don’t let the bedbugs bite.” “Bedbugs?” Lisa said, alarmed. Maggie was lulled to sleep, by “Rock-a-bye Baby,” only to end up dreaming about plummeting from a treetop. As profoundly influential as the maladjusted cartoon family would become—“an achievement without precedent or peer in the history of broadcast television,” as the New York Times critic A.O. Scott put it—only fans of a certain age may recall that the debut of the hapless parents and their strangely recognizable foibles took place close to three years before “The Simpsons” series premiered, in 48 long-lost shorts that appeared on “The Tracey Ullman Show,” the acclaimed but barely watched Fox variety program.

The mostly 20- or 30-second-long segments crash-landed in 1987 onto a TV landscape dominated by wholesomely corny sitcoms like “Growing Pains” and “The Cosby Show.” To create the bumpers, as the filler segments are called, producer James L. Brooks turned to Matt Groening, whose “Life in Hell” comic strip (featuring the musings of angst-ridden rabbits and an identical-looking gay couple named Akbar & Jeff) was syndicated in alternative weekly newspapers across the country. Brooks hoped Groening would turn the comic into a series, but Groening instead proposed a new story of family dysfunction stocked with characters who were, as he later put it, “lovable in a mutant sort of way.”

In contrast with the seamless familiarity of Disney characters or Saturday morning cartoons, the Simpsons immediately stood out. The lines were sharp, jagged, irregular. The kids had pointy heads, and everybody looked as if they’d been electrocuted. And then there were the colors—bright yellow skin, blue hair—added on a lark by the animators, Gabor Csupo and Gyorgyi Peluce, Hungarian immigrants whose tiny animation shop underbid other competitors to win the “Simpsons” contract and threw the colors in for free to clinch the deal.

Looking back at the bumpers now, you discover curious relics. In one, Bart and Lisa watch TV on the couch, but as soon as the show breaks for a commercial the kids immediately begin fighting. (Even back then the family spent a lot of time in front of the TV.) The moment their show resumes, they’re back on the couch, passively watching—an irreverent TV commentary about TV’s hypnotic effects on children.

But these ancestral Simpsons are undeniably of another epoch, more Homo erectus than modern man. And it seems that the differences sit uneasily with the show’s creators. The shorts have never been officially released by Fox, and only a handful can be found on YouTube. (Fox declined to make them available to Smithsonian.) They’re treated less like canon than apocrypha.

Yet the best parts of today’s “Simpsons” share a raw vibrancy with those primitive ancestors. That’s most evident when the show gives itself over unexpectedly to sight gags or visual experimentation, as when artists like Banksy and the filmmaker Guillermo del Toro have been invited to direct the opening credits sequence. The results have occasionally been bold, arresting or just plain silly, which can be good enough.

“The Simpsons,” Time magazine once said, “established a generation’s cultural references and sensibility.” But even so, the show has long since been normalized by its own success, reduced by a parade of gratuitous celebrity guest appearances (Lady Gaga, Mark Zuckerberg) and squeaky clean tropes derivative of the latest pop cultural trend. The oddly lovable mutants Groening first flung at us 30 years ago ushered lowbrow satirical art into the mainstream. And then comedy moved on.

Related Reads

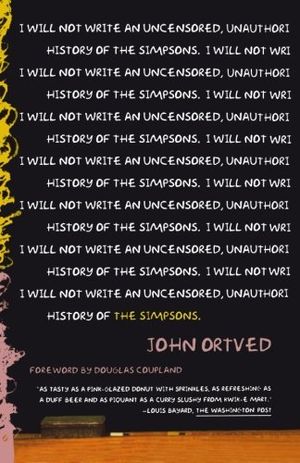

The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History