The Beautiful Game Becomes Beautiful Art as L.A. Museum Puts Soccer on Exhibit

The work of artists from around the world looks at players, fans and the ball itself

Among the many things that baffle the rest of the world about the United States, our failure to fully appreciate professional soccer—“football” or “fútbol” to most other nations—must be near the top of the list. From Argentina to Spain, France to Kenya, the sport is an international obsession, its teams the very embodiment of local, regional and national pride. That fervor will reach its height this summer as 3 billion people turn their attention to the World Cup, in which 32 national teams will vie to determine which country wins bragging rights for the next four years.

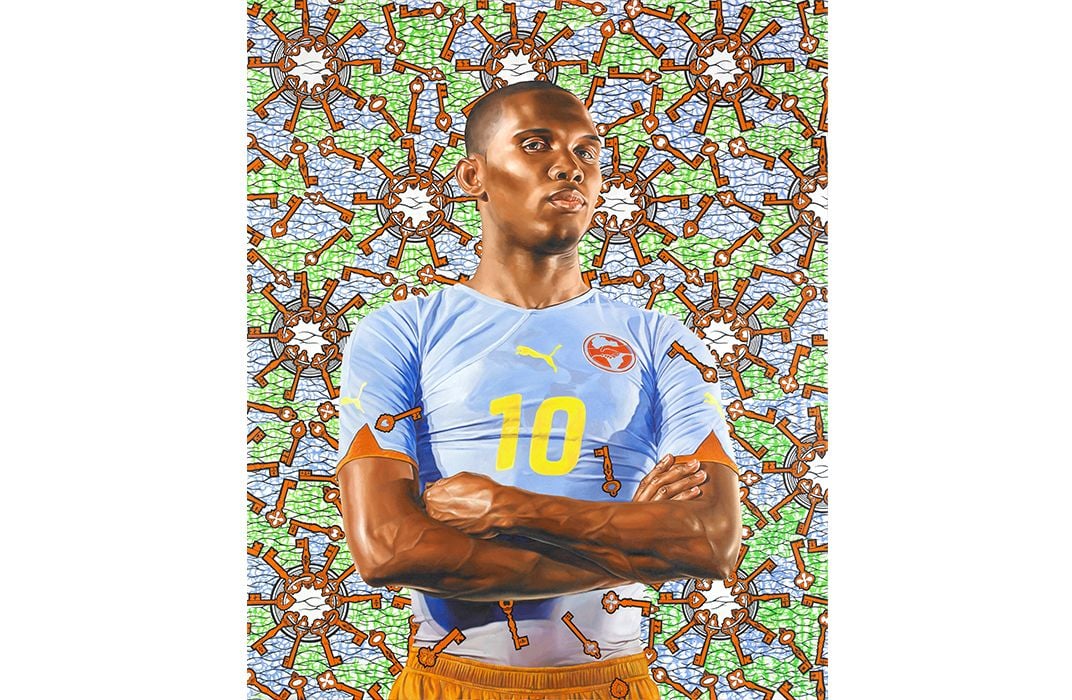

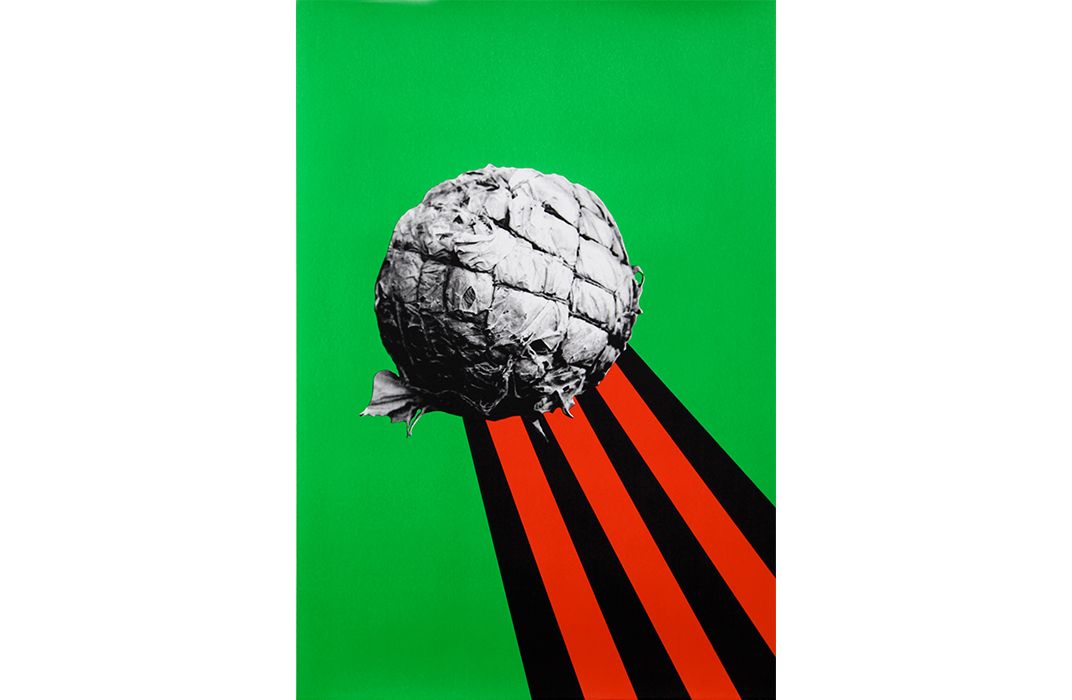

For Americans just tuning in to follow Team USA, a major exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art may help us begin to understand the sport. “Fútbol: The Beautiful Game,” on view through July 20, brings together the work of 30 artists from around the world to explore soccer from the perspective of fans, players, critics and even bemused bystanders.

“It’s a theme that speaks to so many people,” says curator Franklin Sirmans, whose own love affair with soccer began during his childhood in New York, when he idolized the legendary forward Pelé. For Sirmans, a highlight of the exhibition is Andy Warhol’s 1978 silkscreen portrait of the Brazilian superstar. “Warhol was looking at him not just as a soccer player but as an international celebrity,” Sirmans notes.

Pelé may have popularized the moniker “The Beautiful Game,” but it stuck thanks to athletes like Zinedine Zidane, a French player who is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest the sport has ever known. Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s room-sized video installation, Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, follows the midfielder through the course of one 2006 match.

“Anything that is that athletic has an elegance,” Sirmans says. “To me, the Zidane piece is about that individual artistry.”

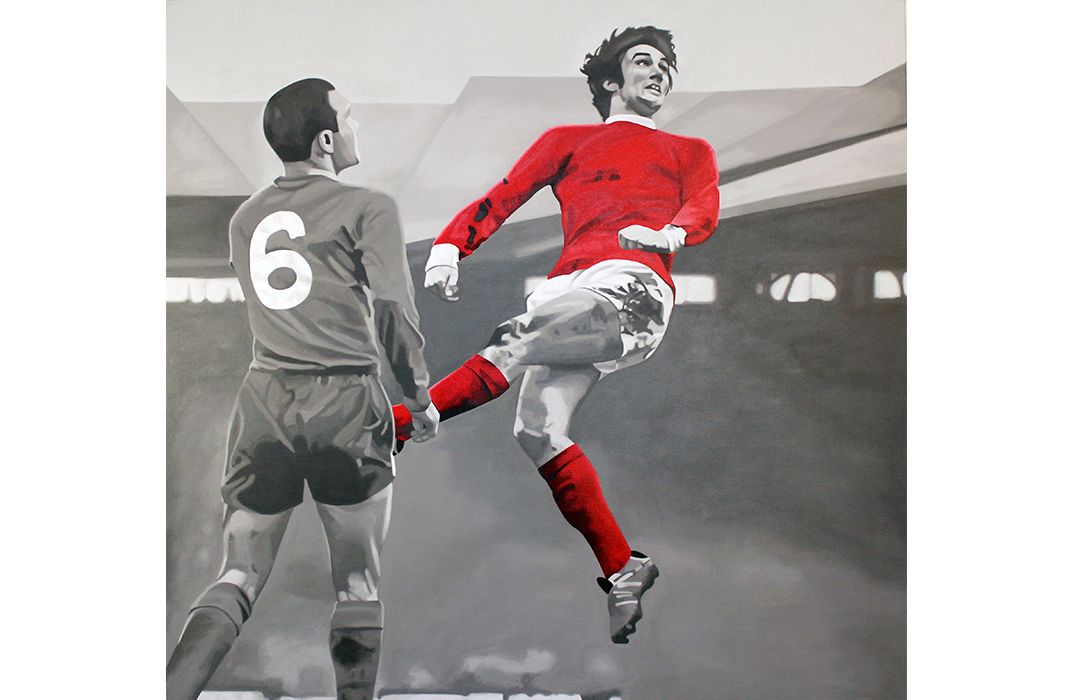

Other footballers the show celebrates include Manchester United stars George Best, Brian Kidd and Sir Bobby Charlton (who helped England win the World Cup in 1966), each of whom L.A. artist Chris Beas depicts in acrylic paintings that resemble classical portraits of heroes.

But soccer culture goes beyond the players on the field. Many of the works at LACMA pay tribute to the sport’s rabid fans, including French artist Stephen Dean’s 2002-03 video Volta, an impressionistic look at a stadium full of Brazilian spectators, and Miguel Calderón’s Mexico vs Brasil. The Mexican filmmaker spliced clips from years of games between the two rivals to show the Mexicans winning goal after goal. (The eventual score is 17-0—highly unlikely in a soccer match, especially since Brazil usually crushes Mexico). In 2004, Calderón played the film in a São Paulo bar as a prank, letting baffled customers think it was a real, live match.

Sirmans says his goal in assembling the LACMA show was to “think of soccer as a metaphor for life, an approach partly inspired by the French writer Albert Camus, who once said, “After many years in which the world has afforded me many experiences, what I know most surely about morality and obligations, I owe to football.”

Camus might have believed that the simple rules of fair play in soccer had plenty to teach us, but the game, like life, isn’t always fair. Wendy White’s 2013 Clavado and Paul Pfeiffer’s 2008 video installation Caryatid (Red, Yellow, Blue) examine the “flop,” the practice of flamboyantly faking injuries in order to win a penalty against the other team. It’s a widely-ridiculed phenomenon that many fans find highly irritating—while others see it as a valid strategy, since cheaters often win in life as well as in sports.

“Not everything is beautiful about the beautiful game,” acknowledges Sirmans. It can inspire an unhealthy tribalism, and even violence among rival fans, he notes. “Nationalism plays such a role, especially in the World Cup.”

English artist Leo Fitzmaurice’s bright, witty arrangement of discarded cigarette-pack tops flattened into miniature soccer jerseys does provoke questions about obsession, the artist’s included. Fitzmaurice doesn’t smoke or follow soccer, but ever since he first spotted a jersey-shaped box top near a Liverpool stadium, he has collected more than 1,000, including brands from countries around the world. “It’s a slightly dirty habit,” he laughs, “but it’s taken on its own life.”

Sirmans says that despite the issues connected with soccer obsession, he remains a “big time” fan. This summer, in addition to the American team, he will be following the fates of Ghana, the Netherlands and Brazil. Sirmans believes more Americans are developing a taste for soccer—which may be why turnout for the exhibition has been so impressive, he adds. “I see little kids coming in with jerseys on, which to me is the greatest thing.”

While they’re at the museum, these young soccer fans may develop a taste for art as well, Sirmans hopes. And perhaps the art enthusiasts who stop by the show will come in turn to appreciate the artistry and pathos of the beautiful game.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/9b/e39b9edc-e60f-4532-84f7-0f355aa4a68c/14.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)