Spirit of the Sea

Tlingit artisans craft a canoe that embodies their culture’s oceangoing past

On the morning of June 19, a crowd gathered in Washington, D.C. to watch a boat plying the Potomac. The distinctively carved canoe bulged with eight paddlers sitting two abreast, while a coxswain beat a drum to keep stroke. "Who are you, and what are you doing here?" shouted a man on shore as the boat began to dock. "We are the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian," a paddler responded, reciting the names of Northwest Coast Indian tribes.

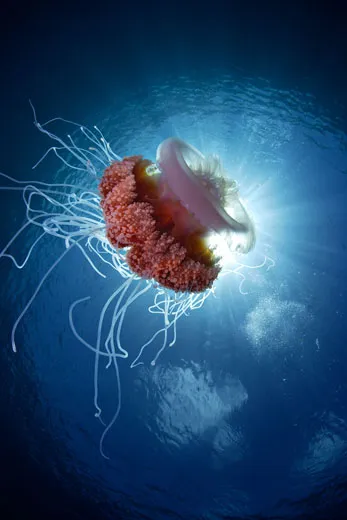

Its maiden voyage complete, the 26-foot dugout canoe, named the Yéil Yeik (Raven Spirit), is now suspended from the ceiling in the Sant Ocean Hall, which opens September 27 at the Natural History Museum. "Human life on earth has in many ways been a response to the challenges of the ocean world," says anthropologist and curator Stephen Loring. The canoe is a "uniquely American watercraft and a powerful symbol of human ingenuity and accomplishment."

For the Northwest Coast Indians—who inhabit the offshore islands and jagged coastline extending from the Oregon-Washington border to Yakutat Bay in the southeastern Alaskan panhandle—the canoe enabled them to avoid geographic isolation. "Our people couldn't be who we are and where we are without the canoe," says Tlinglit elder Clarence Jackson. Indeed, archaeological findings suggest a complex maritime culture at least 10,000 years old.

The Tlingit learned to subsist on the ocean. "When the tide goes out, our table is set" is a common refrain. But despite this intimate connection with the sea, canoe-building fell into decline during the past century. "Everybody had a knack for hewing out a canoe," says Jackson, of the pre-1920 era. Motorboats have since replaced traditional canoes.

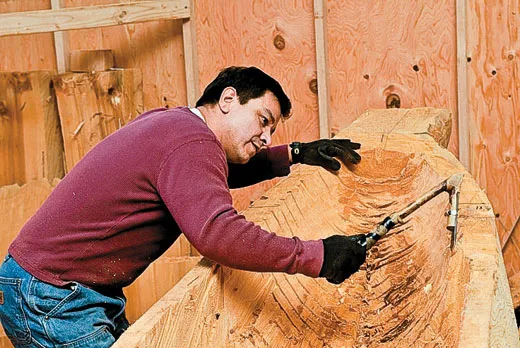

But a few Tlingit artisans, such as Doug Chilton, have sparked a revival. The Native-owned Sealaska Corporation donated a 350-year-old red cedar tree to the Raven Spirit project. Traditionally, carvers would dig a trough down the center of the canoe, light a fire, let it burn awhile and then knock out the charred areas with an ax. To ease their labors, Chilton and his fellow artisans, including his brother Brian, used chain saws. Once hewed, the canoe was steamed, in the manner used by their ancestors, to expand the sides and curve up the ends.

As a finishing touch, they mounted a figurehead of a raven with a copper sun in its beak—to represent the Tlingit legend of the raven bringing light to the world. As if to remind those involved of the spirits at work in the project, a raven, distinguished by a broken wing that forced its feathers to stick straight out, visited Chilton several times while he was working.

"He was almost claiming ownership of the canoe," says Chilton. To honor the wounded raven, Chilton whittled its tousled wing into the figurehead. "The spirit of that raven was there in that canoe."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)